Homestead Economics: Distilling Liquor

Many early American farmers distilled their own liquor, not just for their own consumption but also for additional income.

According to Mount Vernon, where George Washington ran a sizable distillery, the average Virginia distiller had one or two stills and produced around 650 gallons of liquor per year. By comparison, Washington’s distillery had five stills and created almost 11,000 gallons annually!

Andreas Hagenbuch (b. 1715) probably began to distill alcohol at his homestead in Albany Township, Berks County, Pennsylvania sometime before 1770. By then, the family had moved beyond subsistence farming and was focusing more on cottage industries that converted harvested materials into finished goods. For example, flax grown in the fields was woven into linen fabric and animal hides were tanned to make leather.

Similarly, the process of distillation transformed crops into alcohol. Grains like rye, wheat, and barley were used to create whiskey and fruits like apples and peaches were turned into brandy. For farmers, a copper pot still enabled them to take perishable crops that were difficult to transport and, with some added time and labor, change them into liquor—a commodity that could be stored safely in barrels and more easily carted to market. Watch the video below to learn more about the 18th-century distillery at Mount Vernon, VA.

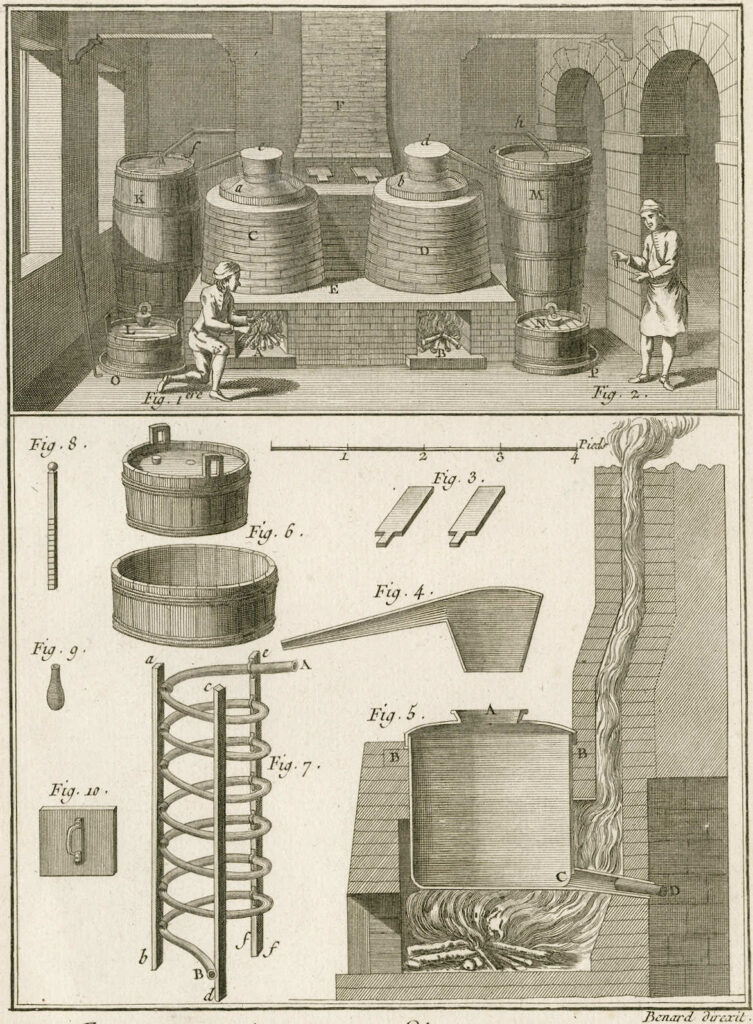

A distillery extracts ethyl alcohol from a fermented mash of grain to make whiskey or from fermented fruit juice to make brandy. The following process was frequently used by colonial distilleries to make whiskey:

- A grain, such as rye, was grown, harvested, and cleaned.

- The grain was ground in a mill to prepare it for cooking.

- In a large barrel, the grain was mixed with boiling water to create a mash. The mixture was set aside to ferment for several days.

- The mash was placed into a copper pot still and heated with a fire. As the temperature of the mixture neared 170º, the alcohol turned into a vapor and separated from the mash. The alcohol vapors would rise into the onion (the bulbous top of the still) and would travel down the line arm into a copper coil.

- The coil sat in a barrel of cold water that was constantly replenished by a spring or creek. Inside the coil, the alcohol vapor condensed back into a liquid—whiskey.

- At the end of the coil, the whiskey emerged and was collected into barrels. In 18th-century America, whiskey wasn’t typically aged and was transported to market. Aging whiskey in burnt oak barrels would not become popular until the 19th century, after the heyday of the distillery at the Hagenbuch Homestead.

- Nothing was left for waste. Once the alcohol was extracted, the leftover mash could be fed to hogs or other animals.

Brandy was distilled in a similar way. However, instead of using a grain, fruit juice or a fruit mash was fermented. Apples were commonly used by the Pennsylvania Deitsch to make brandy. The apples were pressed into cider, which was then fermented. The resulting hard cider was distilled to produce brandy.

Engraving from Diderot’s Encyclopédie showing a two still distillery in 1751 along with the associated equipment needed to distill liquor

In eastern Pennsylvania, apple brandy was and still is known as applejack. This name may come from an an alternative method for creating apple brandy—freeze distillation. Unlike copper pot distilling, freeze distillation required little equipment. A barrel of hard cider was exposed to the frigid cold of winter. Since water freezes before ethyl alcohol, the ice was removed from the remaining cider to remove water and “jack” up the alcohol content of the drink. Historically, applejack was much closer to apple brandy. Some modern applejacks are blends that mix apple brandy with a neutral spirit distilled from grain.

The earliest circumstantial evidence of a distillery at the Hagenbuch Homestead comes from 1771. In that year, Andreas’ son, Henry (b. 1737), purchased a lot in what would become Allentown, PA. There he established the Cross Keys Tavern, and it is believed that Andreas may have funded the venture or, at a minimum, supported it. A reliable supply of liquor would have been needed at the new tavern. This may have been made at the Hagenbuch Homestead and sent by wagon 27 miles east to Allentown.

Two years later in 1773, Andreas purchased 155 acres of land 10 miles north of the tavern. Here he built a distillery, a fact confirmed by the 1789 tax records for Allen Township, Northampton County, PA. Now the Cross Keys had an additional supplier of liquor in close proximity. Andreas put his son Christian (b. 1747) in charge of the distillery and eventually sold it to him in 1782.

When Andreas died late in the summer of 1785, his personal effects included 100 gallons of brandy that was distilled from fruit grown in the orchards on the Hagenbuch Homestead. The brandy was likely made from apples that had been harvested the previous fall. Therefore, what was recorded as brandy was almost certainly applejack. It was also one of the most valuable items in Andreas’ inventory.

Yet, the strongest evidence of a distillery on the farm comes from the inventory of Andreas’ son, Michael (b. 1746). When Michael died in 1809, his estate inventory listed the equipment and supplies needed for distilling: two stills, 35 empty hogsheads, two empty barrels, kegs, small tubs, a trough, 56 bushels of wheat, and 120 bushels of rye.

By one estimate, a bushel of rye can produce at least two gallons of whiskey, meaning that Michael’s 120 bushels of rye could have created at least 240 gallons of whiskey. According to John Gagliardo in “Germans and Agriculture in Colonial Pennsylvania,” an acre planted with rye near Kutztown, PA yielded 15 bushels of grain in 1794. Using this figure, eight acres of land would have been needed at the homestead to harvest 120 bushels of rye or to make 240 gallons of whiskey.

Michael’s inventory included liquor as well: 92 gallons of whiskey and 190 gallons of rye whiskey. It’s notable that “whiskey” and “rye whiskey” are recorded separately. One explanation for the distinction is that the 92 gallons of whiskey were distilled from a grain other than rye, such as wheat or barley. The inventory mentioned two barrels of cider ale too. This was hard cider which could have been drunk as is or distilled for applejack.

Given the number of stills and quantity of liquor present on the farm in 1809, it is reasonable to assume that the family had constructed a distillery at the Hagenbuch Homestead by this time. While it is possible to place a copper pot still over an open fire, this design is inefficient and unwieldy. A distillery is a specialized building that houses one or more stills and protects these from the elements. The structure makes it easier to ferment mash in barrels, control the temperature of the fire under the still, pipe cold water around the condensing coils, and collect the finished whiskey or brandy. A distillery enables the production of liquor throughout the year, regardless of the weather.

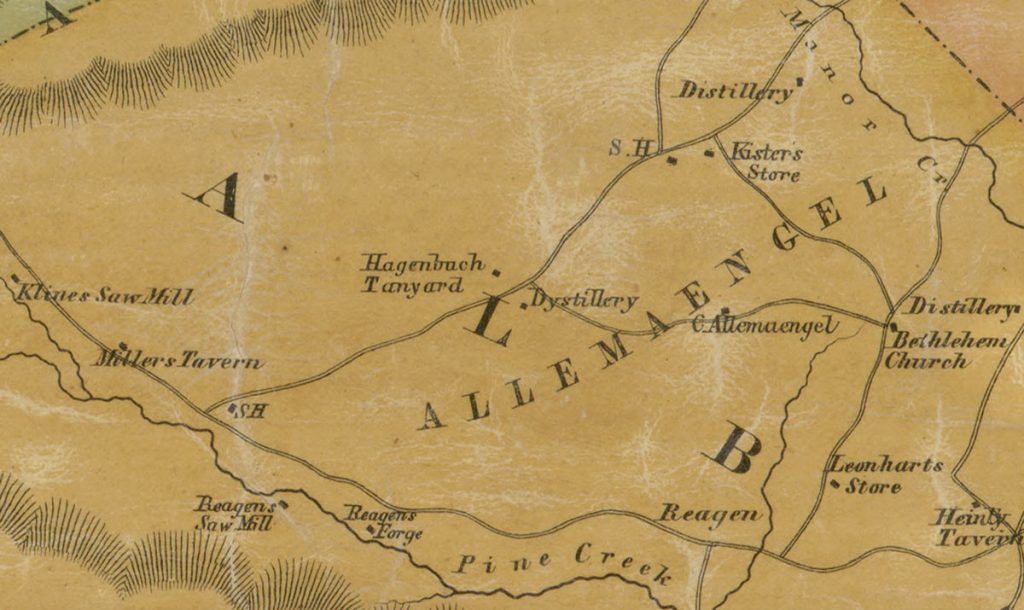

A map of Berks County, PA that was published in 1854 depicts a distillery across the road from the Hagenbuch Tanyard and within the bounds of the homestead property. The map was created from earlier surveys of the county and probably reflects how the area looked around 1830. As described above, a distillery requires a source of cool water, and the location of the building on the map suggests that it stood near a small creek. The distillery may have been constructed in the 1770s, when Andreas owned the homestead. It then continued to operate into the first decades of the 1800s.

The Hagenbuch distillery is noted near the family’s tanyard in the center of this map that was published in 1854

After Michael died in 1809, his son Jacob (b. 1777) inherited the Hagenbuch Homestead. He continued to distill alcohol there, although to a lesser extent than his father. Instead, he invested heavily in developing the tannery at the farm. When Jacob died in 1842, his estate inventory recorded only one copper pot still with a cap and condensing coil. A single barrel of cider royal was listed as well. This drink was made by fortifying hard cider with apple brandy, suggesting that Jacob made applejack for this purpose.

By 1842, when Jacob died, small American distilleries had been on the decline for several decades. There were a number of reasons for this, the first being an increase in market competition. According to Daniel Okrent in his book Last Call, the number of distilleries in the United States quintupled between 1790 and 1810. This drove down liquor prices. George Washington received about 68 cents for a gallon of whiskey in 1799. In 1809, Michael Hagenbuch’s rye whiskey was valued at 32 cents per gallon. By 1820, the price of whiskey had declined further to 25 cents per gallon, as W. J. Rorabaugh writes in “Alcohol in America.”

The second factor in the decline was taxation. In the 1790s, the newly-formed United States enacted an excise tax on whiskey to pay down debt incurred from the Revolutionary War. This reduced the profits of distillers and ultimately led to the Whiskey Rebellion. The whiskey tax remained in effect until 1802, when it was repealed. However, the writing was on the wall for many smaller distilleries—the federal government could impact their businesses through taxation.

A pot still encased in brick. The still, copper onion cap, and line arm are on the left. The arm connects to the condensing coil submerged in the barrel at the center. Water is fed into the barrel through the wooden pipe on the right. A second still for finishing is visible in the lower right. Credit: Eichelberger Distillery at Dills Tavern

The third and final reason was the rise of the temperance movement. The American Society of Temperance was founded in 1826. A little over a decade later, the society claimed to have over 1.2 million members, nearly 8% of the country’s population! American alcohol consumption peaked in 1830 with each adult drinking the equivalent of seven gallons of pure ethyl alcohol per year. Today, the alcohol consumption rate is dramatically lower—2.4 gallons per year.

After Jacob’s death in 1842, his son Michael (b. 1805) assumed ownership of the homestead. Michael appears to have done little to no distilling. When he died in 1855, his inventory mentions no whiskey, brandy, or even cider. In fact, the only clue that the family may have made liquor was the presence of one still kettle with fixtures and several hogsheads. Considering that Michael built a new home and barn in the 1850s, the old distillery may have been torn down and its materials repurposed.

Distilling liquor was an important economic activity at the Hagenbuch Homestead during the late 1700s and early 1800s. The family produced whiskey and applejack, as well as hard cider, for an additional income and for home consumption. Ultimately, market conditions and changing attitudes towards drinking alcohol led to the decline of the distilling operation at the homestead, forcing the Hagenbuchs to focus on other pursuits such as leather tanning, linen production, and agriculture.

Many thanks to Sam McKinney and the Eichelberger Distillery at Dills Tavern for some of the information and photographs used in this article. The distillery is opening in 2024 and recreates a working 18th-century distillery.

Articles in the Homestead Economics Series: