Homestead Economics: Conclusion

This series of articles started with a question: What economic activities contributed to the success of the Hagenbuch Homestead in Albany Township, Berks County, Pennsylvania?

Before beginning to write, I already had some ideas. These were based upon numerous discoveries over years of research. The homestead had a tannery to produce leather. Flax was grown in the fields and woven into linen fabric. A distillery was erected to make liquor. Yet, I had never stepped back to look at the entire operation—the big picture—nor had I considered how these activities related to the broader economic changes in America.

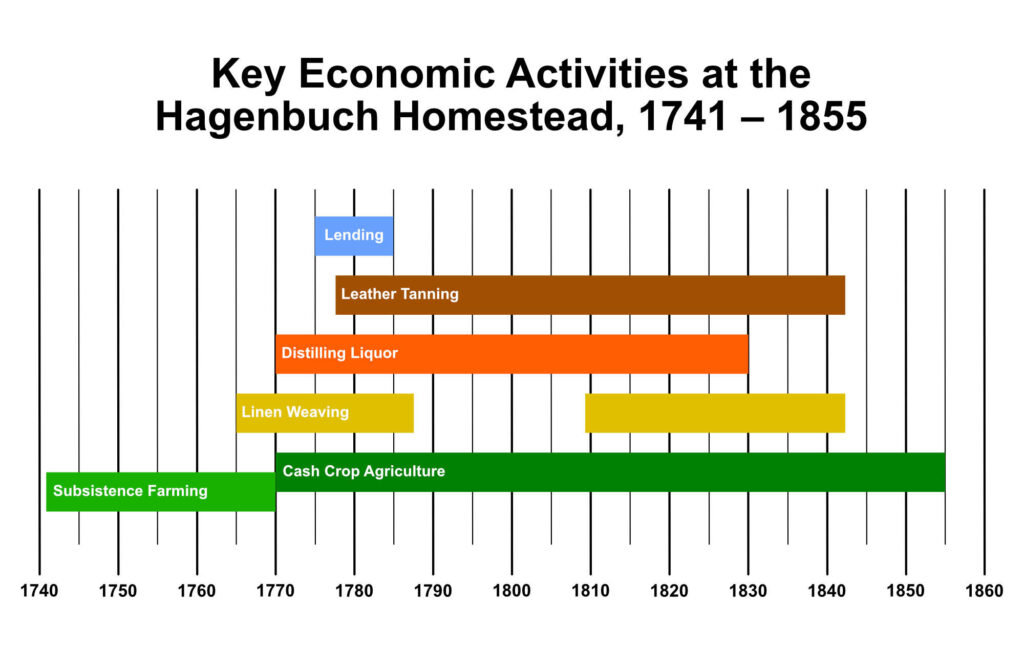

The term homestead often describes a farm, and the Hagenbuch Homestead was certainly that. Founded in 1741 by Andreas Hagenbuch (b. 1715), the land was methodically cleared of trees, crops planted, and livestock raised. Initially, the operation was a subsistence farm—one that focused on providing food, clothing, and shelter for the people who lived there.

Back then, the Hagenbuch Homestead was at the edge of the frontier and took several days to reach from the nearest major town, Reading. Even today, traveling to the site requires traveling off the beaten path. It’s no wonder why our ancestors would have had to be self sufficient. Unfortunately, subsistence farming is hardly a recipe for success.

By the 1760s, Andreas had begun to explore new avenues for making money. These included growing cash crops, linen weaving, distilling liquor, leather tanning, and lending money. Some of the economic activities, like distilling and tanning, were managed by his sons Michael (b. 1746) and Christian (b. 1747). Both would remain important sources of income for decades to come.

Others, such as lending money, ceased around the time of Andreas’ death in 1785. It’s unknown exactly how many loans Andreas made over the course of his life. However, the inventory of his estate made shortly after he died provides insights into his final lending activities.

Andreas had outstanding loans to six parties, the largest being two of his sons, Michael and Christian. Presumably, the loans were made to cover the cost of the properties transferred to both in 1783. Michael took ownership of the Hagenbuch Homestead, and Christian was deeded a large farm with a distillery in Allen Township, Northampton County, PA.

Three loans were to relatives or neighbors. One was to Jacob Kistler (b. 1751) who was a son-in-law and another was to Michael Reichelderfer who was a brother to a son-in-law. A third was to Michael Brobst, who was a neighbor. The final loan was made to Gottfried Seidel, who appears to have been a business contact.

Many of the loans were interest bearing, providing another source of income for the homestead. According to the inventory document, Andreas charged no interest on the loans to his sons. Relatives and neighbors received interest rates between 5–6%. Other parties, like Gottfried Seidel, were required to pay the most—over 11% interest!

There is no evidence that future owners of the Hagenbuch Homestead made substantial loans or collected interest. One explanation for this is that Andreas capitalized upon the lack of banking options in the mid to late 1700s. During this time, those needing credit turned to prosperous friends and family for assistance. Eventually, the establishment of the United States gave rise to a more structured banking system with greater access to currency and credit.

Other economic activities at the homestead trend with developments in American history too. As mentioned earlier, the location of the Hagenbuchs’ farm was isolated. Transporting commodities by wagon was slow and costly, making it inefficient to harvest crops and haul these to market. It made more sense to build infrastructure on the property to process what was produced there.

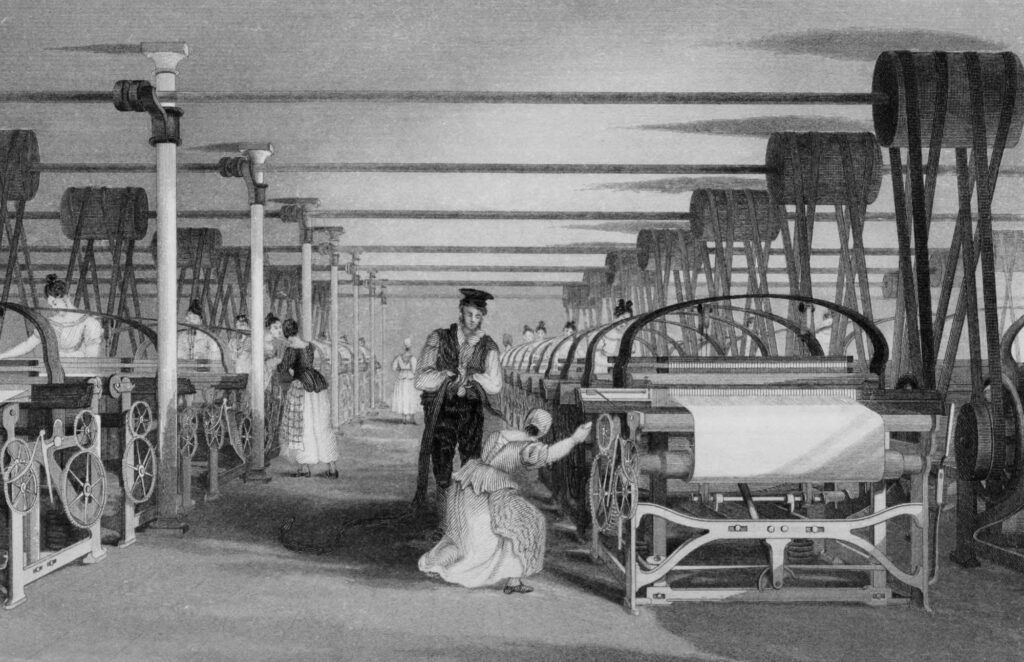

Cottage industries, such as weaving linen from flax, tanning hides into leather, and distilling whiskey from rye, all converted agricultural materials into finished products. Linen, leather, and liquor didn’t spoil as quickly and could be more easily transported to sell at market.

From the 1770s through the 1830s, the Hagenbuch Homestead’s cottage industries created valuable goods from the agricultural resources grown on the land. While a number of elements led to their decline, the most consequential was America’s rapid industrialization throughout the 1800s. New roads, canals, and railroads were built, expediting the transport of raw materials from farms to towns. Mass production drove down manufacturing costs too. This lowered the price of finished goods and made it difficult for small, family-run operations to remain viable.

Changing tastes and attitudes also played a role. By the 1830s, the temperance movement had started to reduce demand for liquor and shrank the market for smaller distillers. Similarly, as cotton production expanded in the southern United States, it became the preferred fiber for textiles that had once been woven from linen. Cotton wasn’t viable in Pennsylvania due to the state’s climate, ending the Hagenbuchs’ weaving business.

It comes as no surprise that by the 1840s the once prosperous cottage industries at the homestead had mostly drawn to a close. The farm refocused on what it could do best: growing cash crops. The Hagenbuch Homestead had come full circle. What had begun with agriculture in 1741 ultimately ended that way in 1855, when the property was sold out of the family.

Of course, there were additional economic activities happening on the farm. For instance, research shows that the Hagenbuchs dabbled in currency speculation and school teaching. However, none of these were practiced on the same scale as those mentioned above.

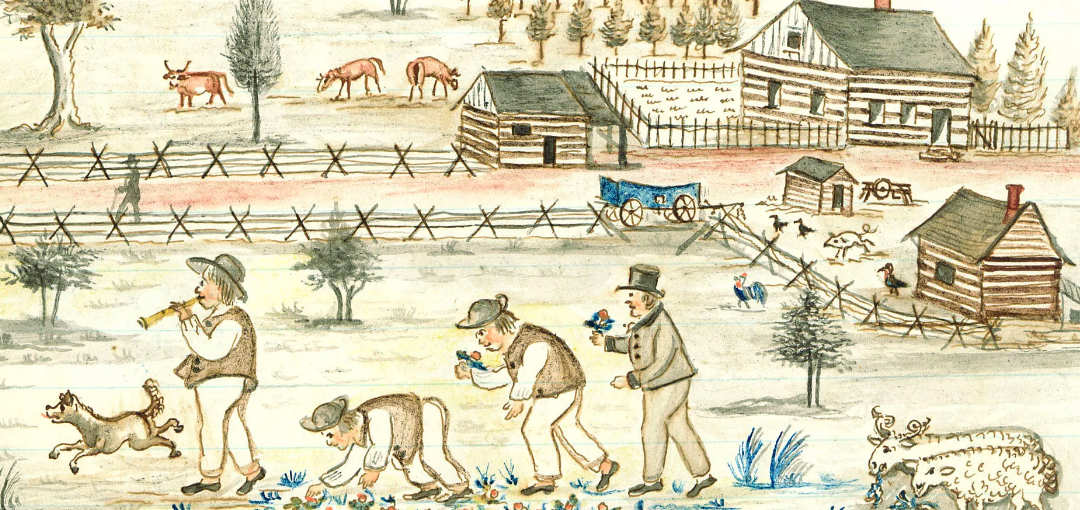

Watercolor depicting the Geiger family’s farm near York, PA in 1810. A man plays the shepherd’s pipe, while others follow behind picking strawberries. Credit: Lewis Miller (b. 1796)

Understanding how our ancestors generated income gives us a clearer picture of their lives. For over 110 years, the Hagenbuch family worked to transform a wooded land of opportunity into a productive farm with pastures, fields, and orchards. Structures were built on the property to house people, livestock, and cottage industries. These include two homes, several barns, a distillery, a tannery, and numerous other outbuildings.

The story of the Hagenbuch Homestead mirrors the early history of America too. Cut from the Pennsylvania forest, four generations of family labored there, adjusting to the changing politics, economics, and fortunes of a young country. Ultimately through hard work, wise decisions, and a bit of luck, they were able to find success and propel us—their descendants—to where we are today.

Articles in the Homestead Economics Series:

Mark,

Nice essay!

Best,

Bob Carl