Your Husband, Ben: Letters from the Civil War, Part 4

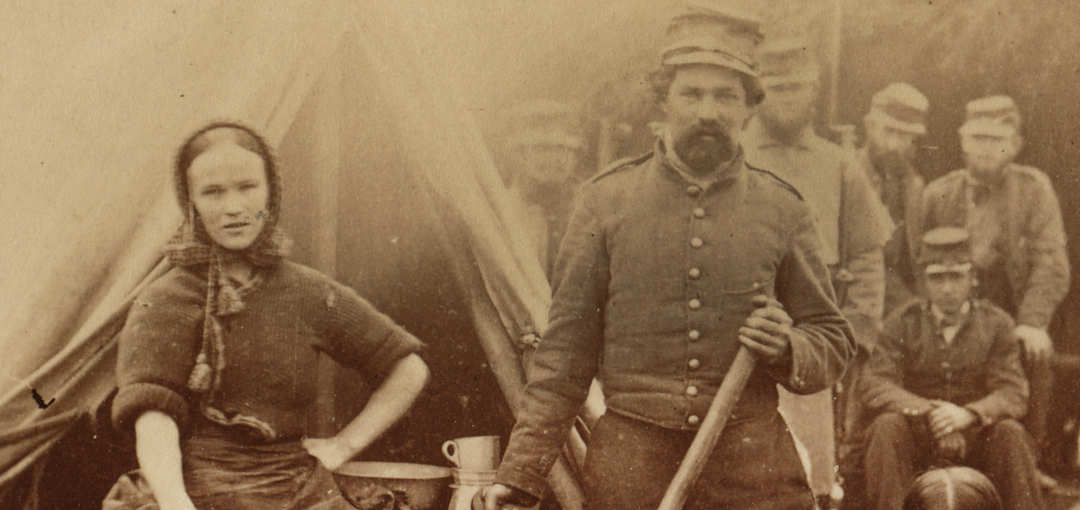

In the previous article in this series, Benjamin “Ben” Del Fel Hagenbuch (b. 1833) was camped near Hatcher’s Run, Virginia, having participated in a battle there. He was assigned to the provost guard, military police that enforced discipline among the soldiers of the 2nd Division, 5th Corps of the Union Army. He resumed writing to his wife, Sarah Jane (Ammerman) Hagenbuch (b. 1831), in late February of 1865. Read Part 1, Part 2, and Part 3 in this series.

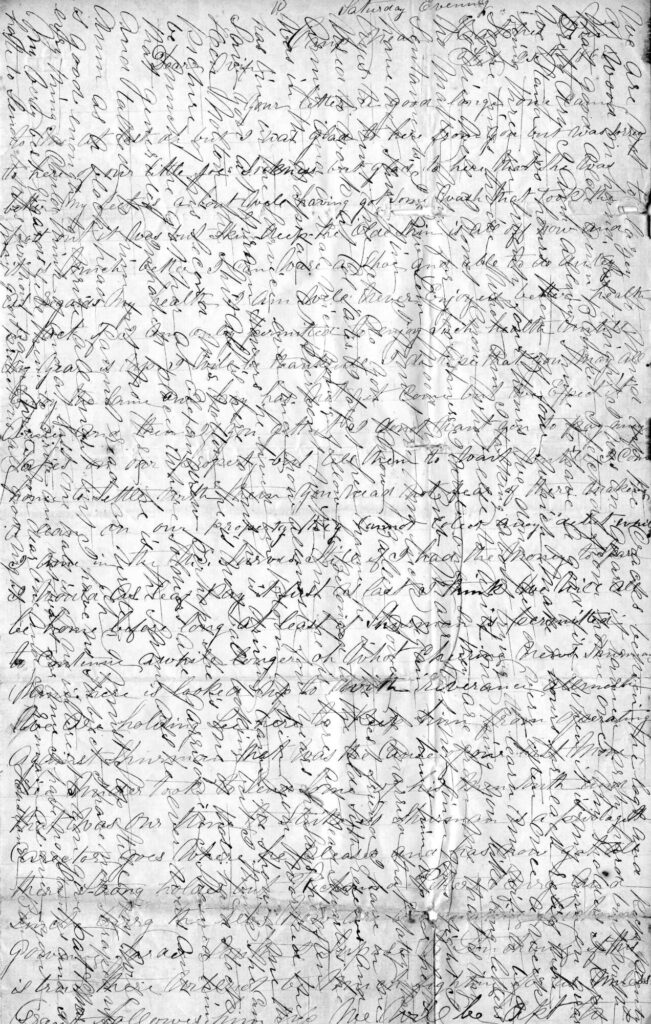

Benjamin Del Fel Hagenbuch Civil War Letters

Part 4: February 25, 1865 – March 10, 1865

Saturday Evening, February 25, 1865

Camp Near Hatcher’s Run, Virginia

Dear Wife,

Your letter, a good long one, came to me at last. Oh but I was glad to hear from you, but was sorry to hear of our little Joe’s1 sickness but was glad to hear that she was better. My feet are about well, having got some wash that took the frost out it—was but skin deep. The old skin is all off now, and it is much better. I can wear a shoe and able to do duty. As regards to my health, I am well, never enjoyed better health. In fact if I am only permitted to enjoy such health until my year is up, I will be thankful. I do hope that you may all enjoy the same.

Pay has not yet come, but we expect it daily. Then if you get it, I do not want you to pay any taxes on our property,2 but tell them to wait until I come home to settle with them. You need not fear of them making a lien on our property. They cannot collect any debit while I am in the U.S. services. Still, if I had the money to pay, I would at least pay it first.

As last [time], I think we will all be home before long, at least if [General] Sherman is permitted to continue awhile longer. Oh what cheering news. Sherman’s name here is looked up to with reverence almost. We are holding [General] Lee here to keep him from operating against Sherman. That was the cause of our last move. Lee undertook to send some of his men south and that was our chance to strike. So Sherman is a privileged character, goes where he pleases, and has now got all there strongholds but Richmond and Petersburg and Lynchburg. The Rebs now are abandoning Richmond, going far and south, I suppose to Lynchburg. If this is true, there will not be much fighting for us, unless [General] Grant follows him up.

We will be apt to make a dash on the South Side Railroad before long.3 If we do, it will be a big fight. Still deserters say that the soldiers are tired and will not fight much more. They average 75 per day from Lee’s army. If nothing else, desertion will soon reduce his army so he cannot possibly hold out. Those prisoners that we took in this last fight—they were surprised to see how well we used them. One asked me if they would be under our charge all the time. I told him, “no,” that we had to turn them over to the Corps Provo and from there they would be sent to City Point. There was some 70 altogether. Then they asked if they would be handled very rough. I laughed at them and told them they would be still treated better, for there they would get something to eat and drink.

They was wishing for coffee. I left one young boy, not more than 14 years old, have my cup to make coffee in and gave him some coffee. Oh but he was glad and said “God bless you.” It was the first coffee he had for six months. If you could, the rations that are given to them for a day, you would think it impossible for them to live and fight as they do. Several showed me their haversacks. All contained the same 4 days rations which was 2 corn cakes, baked without anything but water. They were in this shape [a drawing of an upside down triangle], about 1 inch thick, and six across with a small piece of Bake [text cut off], and that was the contents of their sacks. No coffee, no sugar, no pepper, no salt, or anything but water in their canteens. Most of them had none. When they saw our well-filled sacks with fresh bread crackers, boiled beef or pork, onions, and other vegetables, they thought we had ten days rations. When we told them we had but two days, they were surprised and said, “No wonder the Yankees could fight being fed and clothed so well!”

How they would devour hard crackers. They said they were like shortcake. By the side of them, I exchanged crackers for corn cake with the little fellow. I gave them coffee too, just for a change, and to see how they ate. They tasted like pure corn meal mixed with water and baked on the coals—about as good as salted corn. They get a pint of corn meal a day and use it the best way they can. If we had to fare like them, the spirit of the army would not be worth a cent, and they would not fight neither. It is the opinion of all the whole army that the war is pretty near an end. Oh I hope it is, for what rejoicing would there be and nowhere more than in my little family.

Oh but if I ever live to get home safe and sound, I will promise to be a different man, try and live as we should. Old age is coming on. We may not feel it yet, but surely will here in many years more. That should be a warning, if nothing else. So my Dear Wife, let us try and do all the good we can and pray that God will bless us and keep us safe from harm, so if we are not permitted to meet on earth again, may we meet in heaven.

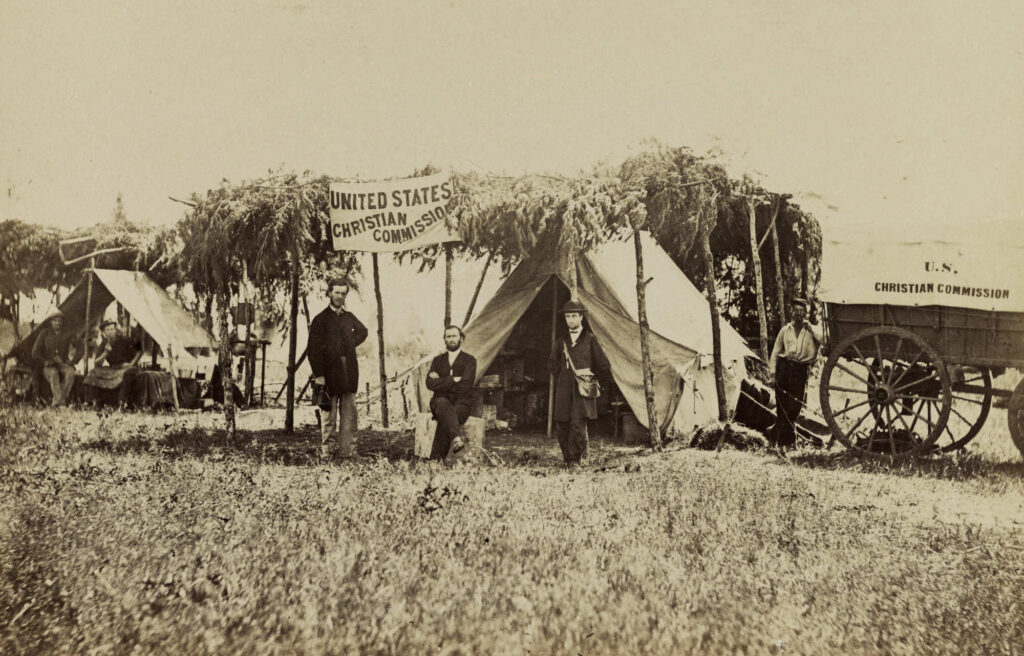

I feel that God will protect me if I ask and ask in the faith that He can. I also ask you to pray for me that I may be spared to return once more to my little family. The Christian Commission have a large church tent in every brigade. They have preaching almost every night. They have or had just before this move some of the biggest revivals I ever saw. You can tell those at home who say the Christian and Sanitary Commission4 are of no acceptance in the army and only money thrown away, that I said they are fanatics and know not what they say and know nothing about it, and are too big a cowards to come down here and see, or too stingy to give a cent for the help of us in the field.

I can tell you of what benefit they are. If the soldier’s shoes are wore out on a long march and none in his company, the Sanitary Commission is at hand with a supply. So it is with everything. All can get, if they have no money, clothing of every kind: thread, needles, pins, buttons, fine combs, shoe strings, tin cups, plates, and knives. Their large, four horse wagon, as much on as the horses can draw, is always with us on a march or in a fight or in camp. All the same, I must close for tonight. All the boys have turned in. There is heavy cannonading going on down near Petersburg. Tonight I think it is only salutes, for it is too regular for an engagement.

When you write again, tell me if ever you got that letter I sent the cotton in. You never mentioned it. Day before yesterday I sent you a letter with two rings in.5 This is the third I have sent since last Saturday. Well, I heard tonight that we will get paid tomorrow. As soon as I get it, I will write to you. I think I will send it by express to Jackson. We will get but four months pay and one installment. I would like to keep some and get some barber tools, if I cannot come home. I know I can make it pay like fun, for the boys will all be flush [with money] now, and I must manage some way to make it pay. An old man arrived here from up about Wilkes-Barre tonight hunting the 210th Regiment. He came for the body of his boy that was killed in this last battle. I told him where he could be found. He will take him up tomorrow. The old man takes it pretty hard. I must now stop.

I got a letter from Uncle Reuben6 tonight. They are well. Nothing is looked for or talked about now but peace. We think it must come soon. I am so glad we have comfortable quarters again, for oh how it rains tonight and has been all day and last night. We have a roaring big fire in the chimney. We can read or write by its light while the rain dashes on the canvas roof. Oh how nice it sounds and how I can sleep when I lay awake. This letter for tonight I have tried several times to stop, but I cannot. Everything appears so cheery and comfortable that I almost feel content with the life of a soldier. If you all and I keep well, I will keep up good spirits until my time is up, for if once a man gets downhearted he might as well go to the hospital at once. For all I think so much of our cozy house and nice shelves of poles to lay on with pine tops for a bed tick,7 we have had better shelter for our hogs at home! Our motto is no matter how ugly, only so we keep dry and warm, which we can easily do if we are not too lazy to mend up the cracks between the logs and keep plenty of wood on hand.

Last night I was on guard. It rained pretty hard, but with that good old gum blanket8 I fetched from home over my shoulders, I kept pretty dry. I am always sure to have a good fire when it is my turn on guard. We stand two hours, then off four, which make 8 hours for each relief, there being 3 in twenty-four hours. We do not get on [guard] very often—once a week, sometimes twice. What am I talking about trying to learn my wife to be a soldier. Well, I don’t know what else to write. One thing you like: long letters no matter what for foolishness I write, only so they are from me. That is my sentiment.

I saw Lem Mood and Bob Marr, but not since this fight. I have not seen Jim. I must try my luck again to hunt him up, or he never tries to hunt me. Oh do you know Baler Hower?9 He married that fatty that used to work at Col. Lates. I forget her name. He is the best friend I have in the army, and a real nice young fellow. He belonged to the old 6th Regiment and was in the hospital at Pierpont with me. He is here at headquarters. He has been in the service, ever since now almost four years. He says he often saw you at Hiram Hower’s. He lived in [Bloomsburg] when you worked there. Hen Nolton, the shit ass, is here too, but he is driving teams. He showed me the picture of his second Mrs. Nolton. She is not tall looking, but I think she cannot be much. He got her at [Alexandria, Virginia]. Perhaps she is one of that hard stock that generally inhabits places where soldiers are garrisoned.10 I showed him and talked to him, but no use he is the same ass he ever was and dumb as a blockhead, cannot read or write. Oh, I must stop. Still my will is good enough to write all night, but I have no subject! I have now scraped up everything I could think of and at least one half is of no interest to you. Give Pat & Mary my very best regards. Tell them to write and not wait for me. I have no stamps yet, and I hate to send letters without being paid.

Write soon, Dear One, and I remain as ever, Your Husband,

Ben

May God protect us all. Good Night.

I sent two papers: one to Rob and one to Willie.

Harvey is not at home or I would send one to him in Danville next time I get any.

Saturday Evening, March 10, 1865

Camp Near Hatcher’s Run, Virginia

Dear Wife,

I take up my pen to write you a few lines, hoping they may find you all as they leave me in good health. I received your kind and ever welcome letter the night before last and would [have] answered it sooner, but they keep us guards so busy since the fight, guarding stragglers and Coffee Coolers11 that sneaked out of the fight, that we hardly have a night to ourselves. I was on all night last night and oh how it rained. It rains pretty near every day and night. What mud. You would hardly believe how bad it is. To get out of camp is almost out of the question.

Jim [Chamberlain] was here yesterday. He sent 50 dollars to Jack. I hope by this [letter] you have yours. I never thought or I would [have] sent a little in a letter. It is too late now. I have commenced barbering.12 I think I can make it pay pretty well. I am glad you got them rings. I hope they fit. I think they were pretty good ones. When I write again, I will try and send some of them shells. In this part [of Virginia], they are not so plenty but still there are thousands. I wish they had their original colors, but they are faded all white. Still perhaps they would be a curiosity to you to see what the soil of this part of the sunny South is composed of.

At one time, perhaps thousands and thousands of years ago, this part of Virginia was one immense ocean and the happy playground of fishes of all kinds. But now it is contested over by two of the greatest armies that ever came into contact, since the world began. One can say with truth that it is nothing but a mammoth graveyard. But enough of that. I dare not get sentimental, for I couldn’t find the words to express my feelings when I take time to reflect if I wished to.

I was surprised to hear that John had enlisted. I did not think he could make up his mind to go to war. His mind is so changeable. Well I hope he has got into a good command and does not come down to the front, for soldiering here is a different profession from the Sunday soldiering at or near home. I am glad Pat can get clear for fifty dollars.13 You asked why so many drafts, if the war was pretty near over. One thing is there is quite an army whose time is up this spring.14 Another is to get a big army and let the Rebs know that our men, as well as our means, are not yet exhausted. With a big army, we can surround them and pen them up without much fighting or loss of life, which I hope and pray we may soon do. We look daily for news that says peace is once more a blessing in United States, and that the cause for which some of her best sons have shed their life’s blood has at last conquered and peace once more reigns.

I am glad to see that Robert is improving in his writing and nothing gives me more pleasure than to see a few lines of his in everyone of your letters. I will send him and the rest all the books and papers I can get. I know that he is like his pap, good-natured and tenderhearted. If he is wild, it will I hope leave him, when his oats are all. Tell him he shall have the best sled next winter that runs on the hill and a wheelbarrow too. Tell Willie that I will remember her with the rest. I suppose Harvey is up the creek yet. Oh but I would like to see you all. I want you to get your pictures taken—I want all—and if I cannot get home on furlough, I want you to send them. Get daguerreotypes for ambrotypes cost too much, but suit yourself.15 Perhaps the last would be the nicest. It must be very sickly up there according to accepts [sic]. I hope you will get your house in the spring. There is no need of me telling you to fix it up in the best shape you can, for that you will do anyhow if you have the means, which I think now I can keep you supplied with [the remainder of letter is missing].

Footnotes

- This is his daughter, Clara Josephine Hagenbuch (b. 1863).

- Mention of property taxes suggests Ben and Sarah owned a home now. (They did not in 1861 when the war began.)

- The Southside Railroad was an important Confederate railroad running from the James River to the areas near Petersburg and Lynchburg, Virginia.

- The United States Christian Commission was an organization that provided supplies, medical services, religious literature, and Protestant chaplains for the Union Army. It worked in partnership with the United States Sanitary Commission, an organization which provided support to sick and wounded Union soldiers.

- The rings were previously discussed in Part 4 as carved from wood or seeds.

- This is believed to be Reuben Bomboy (b. 1811, d. 1898).

- Ben is describing the design of the beds in the canvas-roofed cabin. They include a shelf-like platform made from wooden poles covered with soft pine sprigs.

- Gum blankets were similar to tarps. They were made of heavy canvas that was rubberized on one side.

- This appears to be John B. Hower.

- Ben seems to be describing Nolton’s second wife as a camp follower, and clearly thought very little of him or her.

- “Coffee coolers” were worthless soldiers or cowards who would rather watch their coffee cool than fight.

- Ben is running a side business, barbering men in camp.

- “Get clear” references avoiding the draft. Men could sometimes legally pay a fee to do this.

- Ben is explaining that many men’s enlistments will expire in the spring of 1865, requiring new men to be drafted.

- He appears mistaken about different photographic processes. Ambrotypes were developed as a less expensive alternative to daguerreotypes.

He really impresses me with his fairly extensive vocabulary. I really like reading old letters, it shows what life was like back then.

Thanks Mark and Andrew for this series!

Thanks, Uncle Bob! The letters have a lot of spelling errors (which have been cleaned up) but otherwise, yes, Ben does have great descriptions of what he sees, feels, etc. The salty language in this one really surprised me when I was working on it too 🙂 He clearly didn’t care for Henry Nolton!

Thanks for taking the time to do such a thorough read of my ancestor’s letters. Your explanatory notes are also very helpful. The letters show that the war was tough on the families back home, as well as the men pushed to endure such things as the raid that Ben describes.

Glad you are enjoying them, Dore! They certainly reveal more about the lives of our family and your direct ancestor too. What a great piece of history to still have today.