What’s in a Bible?

What’s in a Bible? I mean this literally. If you open up a Bible, what might you find inside?

In June my father, Mark, and I were going through several boxes of family ephemera. They were full of letters and papers, a few photographs, and a couple of books. One of these books was a Bible and a large one at that.

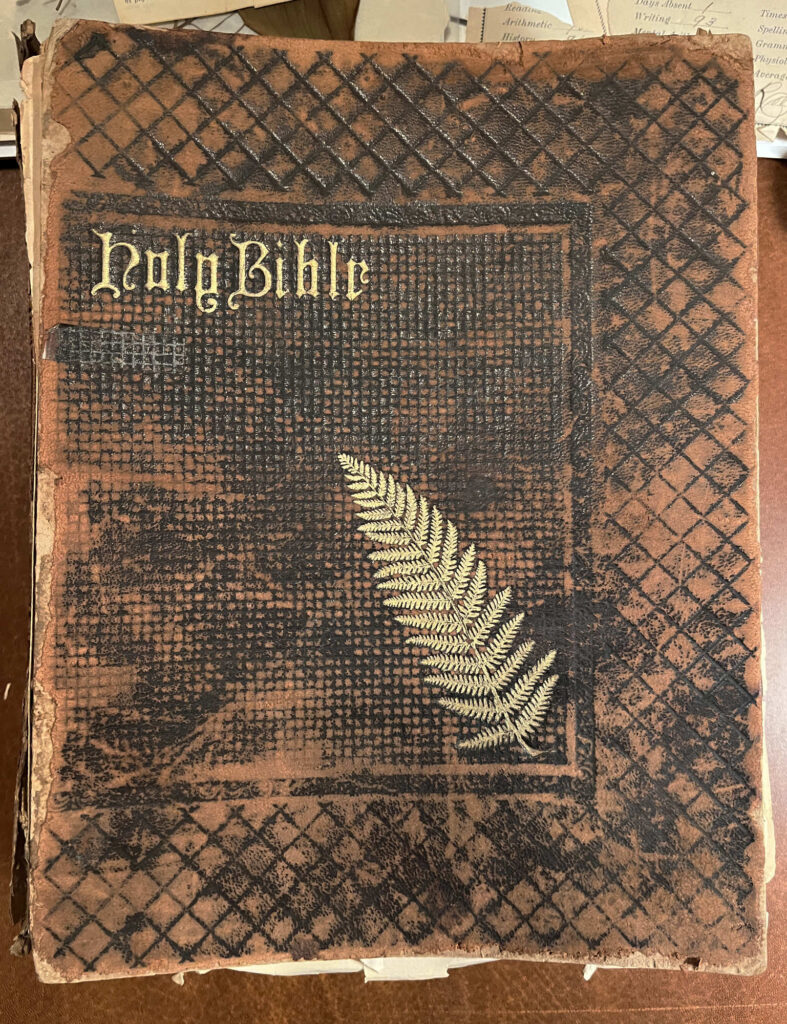

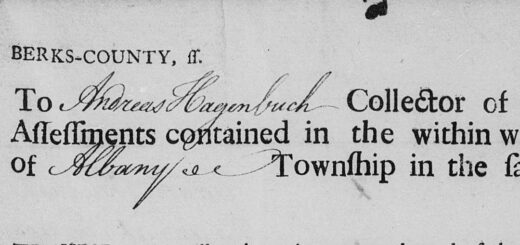

It had been owned by my great great grandfather, Hiram Hagenbuch (b. 1847), and served as his family’s Bible. It was in very poor shape. The faux-leather cover was detached, the binding was broken, and numerous pages were falling out. My father and I discussed if it was worth keeping at all.

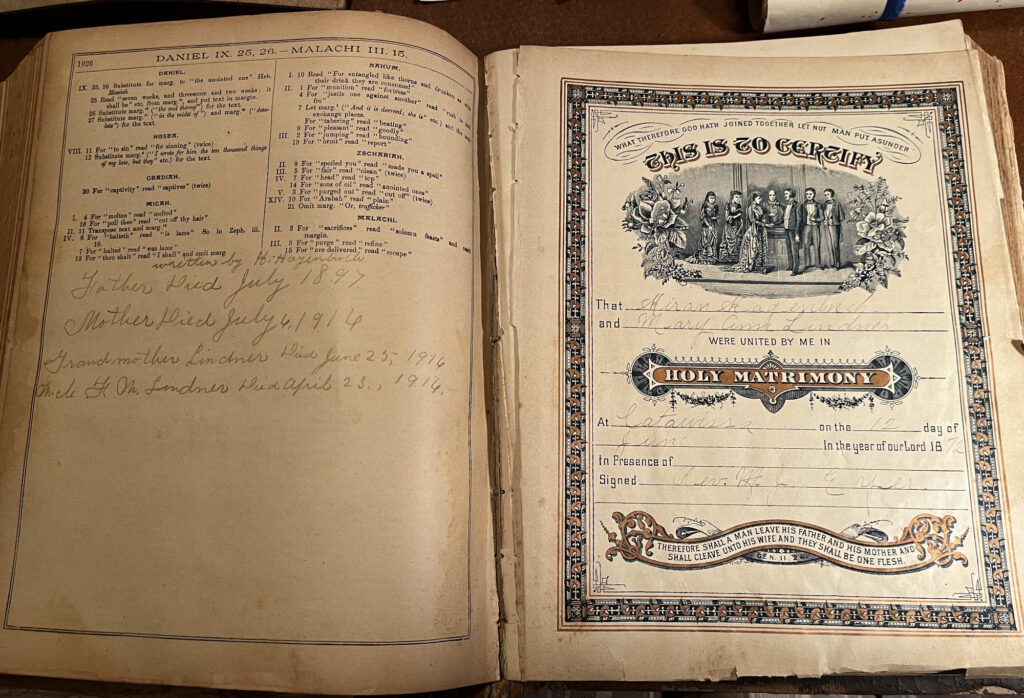

Of course, there was one part of it that we definitely wanted to hold onto—the original family records put down onto a few pages in the middle of the book. The records included information about Hiram’s 1872 marriage to Mary Ann Lindner (b. 1853) written by Rev. M. J. Eyer, details about the couple’s children inscribed by Mary Ann, and the death dates Hiram and Mary Ann entered by their son, Hiram Jr. (b. 1886), who went by “Harry.”

How the Bible came to be in my father’s possession was a bit murky. It seems likely that it was given as a wedding gift to Hiram and Mary Ann (Lindner) Hagenbuch. From there, it remained with the family until sometime after Hiram Hagenbuch, Sr. died in 1897. The Bible next went to his son, Hiram Jr., perhaps in 1912 when he married Bessie Edna Lake (b. 1890).

Death records written by Hiram Jr. (left) and the marriage record for Hiram Sr. and Mary Ann (Lindner) Hagenbuch (right)

It stayed with Hiram Jr.’s family until after he died in 1979. According to my father, around this time Hiram Jr.’s daughter, Helen (Hagenbuch) Styer (b. 1923), gave the Bible to her first cousin, Julia C. Hagenbuch (b. 1915). It was Julia, finally, who passed it to my father.

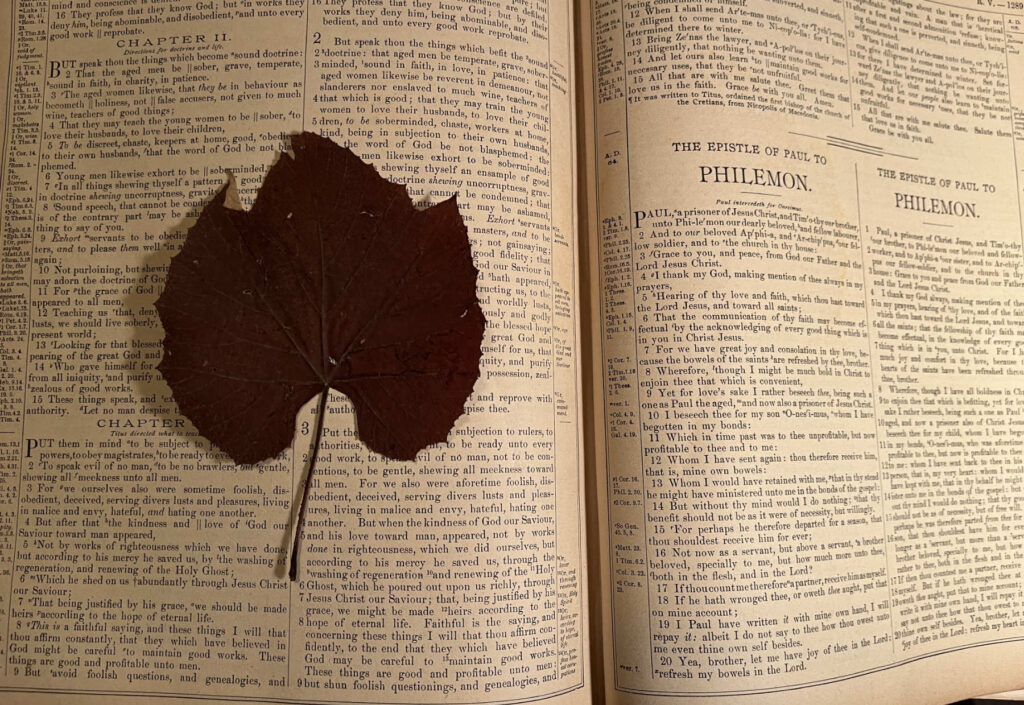

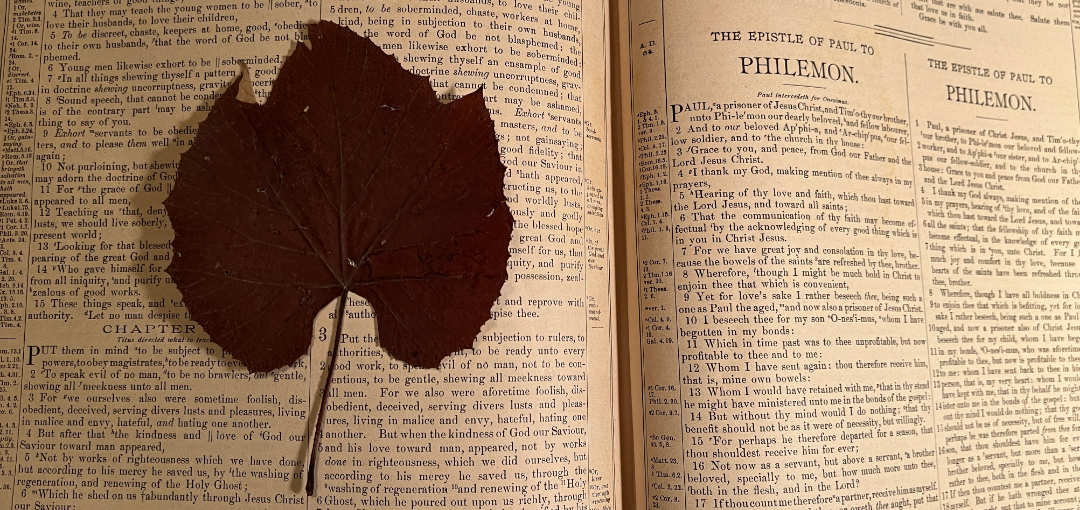

Flipping through the Bible, my father and I admired the images of Biblical scenes. This type of Bible was clearly meant for more than just the reading of the text. It was an educational resource, filled with pictures, maps, and diagrams. As we explored the tome, we noticed something unexpected: pressed leaves, flowers, and scraps of paper between the pages.

At first, we wondered if these were placed there by Mary Ann (Lindner) Hagenbuch. However, after inspecting the items, it appeared more probable that they were added by Hiram Hagenbuch Jr. or someone else in his household during the early 20th century.

The leaves and flowers were particularly interesting. There were at least 10 in the Bible including catalpa, wild grape, maple, and clover. Why were these saved? Perhaps they were for a project or maybe someone was beginning a collection? It’s difficult to say.

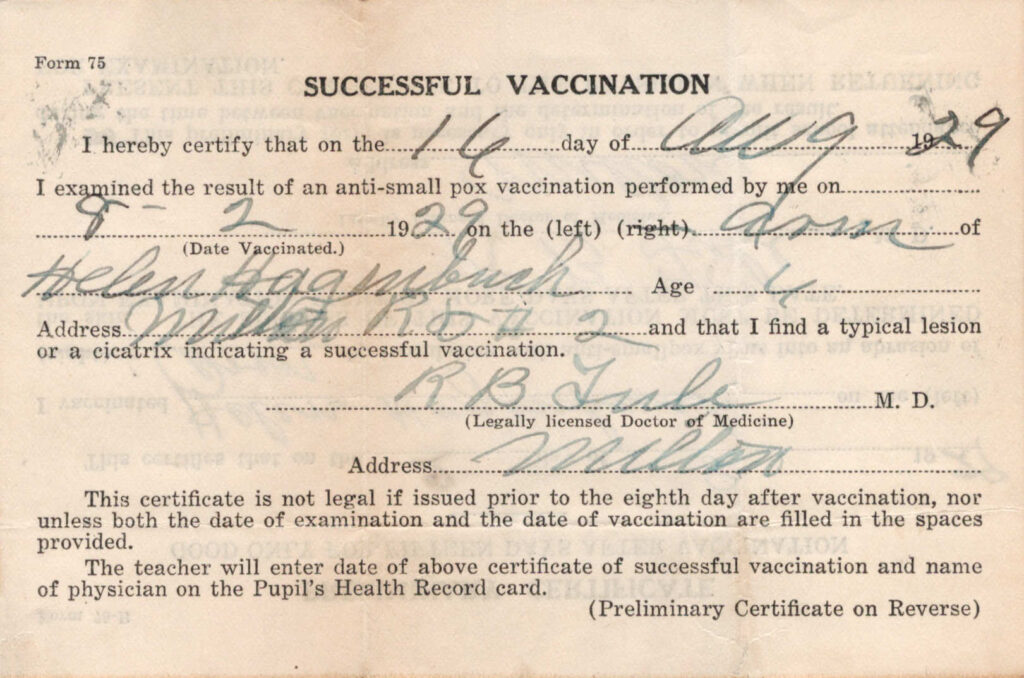

We also found a vaccination card. This artifact was really fascinating. The card showed that Hiram Jr.’s daughter, Helen, had received her smallpox vaccine on August 2, 1929 in Milton, Pennsylvania. It was administered by Dr. Robert B. Tule. Helen returned on August 16th to check that her arm showed the lesion indicating that the vaccine had been successful. In small print, the vaccination card describes that it should be presented to a teacher at school. Helen, six years old at the the time, was receiving the smallpox vaccine before starting public school.

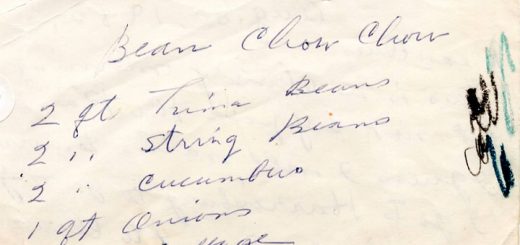

The final two objects found in the Bible were Valentines. One was decorated with rabbits, flowers, and a butterfly. It was sent in 1914 by someone from Baltimore, Maryland to Hiram Jr. and Bessie (Lake) Hagenbuch near Pottsgrove, Montour County, PA. Though a nice piece, it was the other Valentine that really caught my attention.

This heart-shaped memento was handmade from ruled paper, decorated with red watercolor paint, and signed in cursive. The sender was Clarence Messersmith and the recipient was “Roy H.” According to an article about the family of Hiram Jr. “Harry” and Bessie (Lake) Hagenbuch, they had a son named Roy Harold Hagenbuch (b. 1916). He appears to be whom the Valentine was given to. But who was the thoughtful sender, Clarence Messersmith?

Hiram Jr.’s maternal grandmother was Catherine (Messersmith/Messerschmidt) Lindner (b. 1827). This was a good place to start, so I thought. After researching her siblings I came up empty handed. None seemed to have a descendant named Clarence! I took a different approach and looked for a Clarence Messersmith near the place where Hiram Jr.’s family was living in Liberty Township, Montour County, PA. This yielded a hit: Clarence LeRoy (b. 1908) who was the son of Jesse Benjamin and Ada Olive (Treibley) Messersmith. Given the age difference, Clarence and Roy wouldn’t have been in the same class together, so their relationship must have been familial.

Valentine from Clarence Messersmith to Roy Hagenbuch, c. 1917. Closed on left and opened on the right.

Working backwards from here I was able to make a connection. Clarence and Roy were third cousins once removed. In other words, their last common ancestor was two generations before Catherine (Messersmith) Lindner. Although they were distant cousins, it seems clear that the Messersmith/Messerschmidt family in Montour County was close—close enough that a young Clarence, perhaps eight years old, gave his infant cousin, Roy, a Valentine in 1917. Roy’s parents then tucked the keepsake into the family Bible, where my father and I found it over a century later.

What’s in a Bible? Well, it certainly depends upon the owner of it. In the case of this Bible, once in the possession of my great great grandparents, quite a bit was tucked between its covers. While the Bible itself has deteriorated beyond repair, the memories and artifacts between its pages continue to delight and share their stories.