“Wahres Christentum”: Andreas Hagenbuch’s Gift to His Son

Andreas Hagenbuch died in 1785. Previous articles have examined his last will and testament, as well as the inventory of his estate.

- See the full text of Andreas Hagenbuch’s will

- Read an analysis of the will

- View the inventory of Andreas Hagenbuch’s estate

- Look at photos of items in the estate inventory

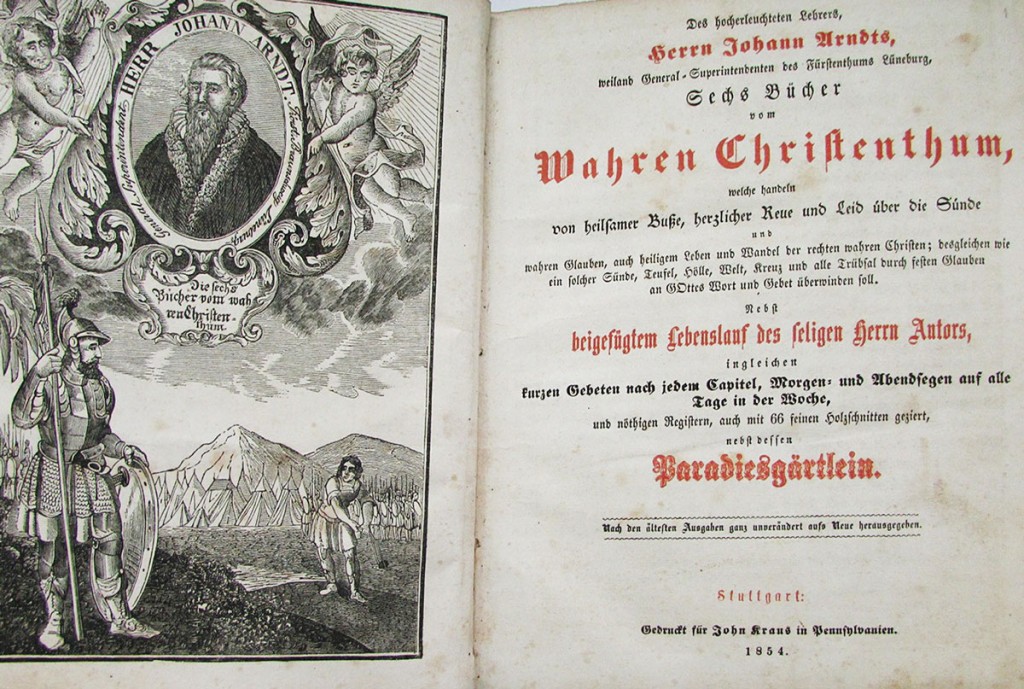

One of the unique items noted in his will is the book Wahres Christentum (English translation: True Christianity). This book was given to his youngest child, John Hagenbuch, and is the only book mentioned in the will.

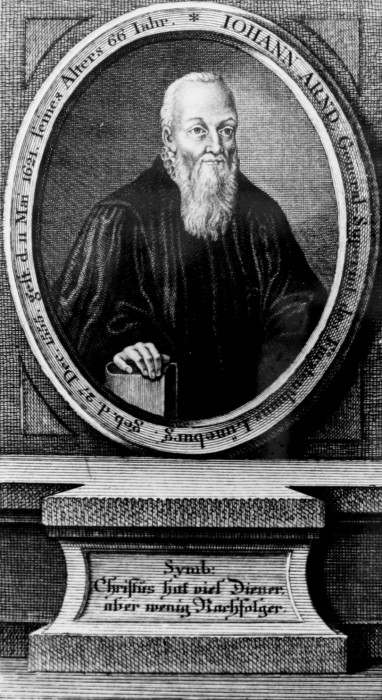

True Christianity was written by Johann Arndt and published in its entirety in 1610. Arndt (1555-1621) was a German Lutheran theologian. He wrote multiple books on the topic of devotional Christianity. These discussed the idea of forming a personal connection to faith in order to achieve self improvement. Some have characterized Arndt’s writings as a form of Christian mysticism, where followers surrender themselves fully to Christ in order to know Him more fully.

Arndt and his book, True Christianity, are widely seen as the forerunners of the Lutheran Pietism movement. In fact, the founder of Pietism, Philipp Jakob Spener, cited Arndt’s writings as a deep inspiration to his ideas. As a result, Lutheran Pietists often read and studied from True Christianity.

Pietists disagreed with the highly structured orthodoxy that defined Lutheranism from around 1580 to 1730. Instead, they argued for a more personal connection to the church. Their other beliefs included studying the Bible in small private meetings, practicing Christianity as part of everyday life, and having the laity help to guide the spiritual direction of the church.

Given Pennsylvania’s religious tolerance, many whose beliefs had been persecuted immigrated to the colony from Europe. Lutheran Pietists were among these. Seeing that Andreas Hagenbuch owned a copy of True Christianity, it is entirely possible that he was a Pietist and religious freedom was one of family’s reasons for settling in Pennsylvania.

This line of thinking also fits with what is known of the Hagenbuch family’s connection to New Bethel Church. Located about half a mile from the homestead, the Lutheran church was organized in 1761 by families in that area of Albany Township, Berks County. Yet, Andreas’s name is conspicuously missing from the names of the church’s founders. And, while Hagenbuch children born after 1761 were baptized at the church, the family preferred to bury its own at the homestead until at least 1842.

Did Andreas Hagenbuch and his family eschew the organized structure and orthodoxy of the Lutheran church in favor of private Bible studies and meetings? It’s impossible to know for certain. What’s clear, however, is that Arndt’s book, True Christianity, was valuable enough that it received a specific mention in Andreas’s will. Although, this only leads to another question. Why did Andreas will it to his youngest child, John?

John Hagenbuch was born on October 4, 1763. When his father died late in the summer of 1785, John was only 21 years old. One way to interpret the giving of True Christianity to John is that the young man valued this book. Perhaps, like his father, John appreciated Arndt’s writings and held the Christian faith in high regard.

Alternatively, one could also look at the gift as a message from the grave. Remember that one of the tenets of Arndt’s book was actively living one’s life through Christ. Perhaps, much to the disappointment of his father, John had abandoned the values that Andreas had worked to instill in him? Might the stereotype of the wild and rebellious youngest child have existed even in the 18th century?

While this line of thought may seem far fetched, there is growing evidence to support the theory that John strayed from the Hagenbuch family and may have been a source of worry for his father. This will be explored in more detail in a future piece.

Supposition aside, Johann Arndt’s book, True Christianity, was an important possession within the early Hagenbuch family. It’s mention provides a fascinating look at the family’s religious beliefs and at Andreas’s relationship with his son, John.