Thoughts on Timothy Hagenbuch’s 1851 Letter

Timothy Hagenbuch’s 1851 letter to his brother, Enoch, is an important piece of history. Besides providing insights into family relationships, the letter reveals reasons why some Hagenbuchs picked up and headed west.

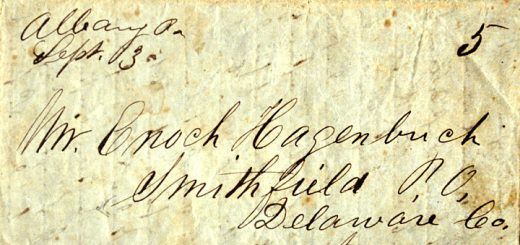

When the letter was written Timothy (b. 1804, d. 1852) was living near the Hagenbuch homestead in Albany Township, Berks County, Pennsylvania. Enoch (b. 1814, d. 1895), on the other hand, resided in Smithfield, Delaware County, Indiana.

Timothy opens his letter by stating that all is well with their siblings. However, a “stomachache” is going around and some neighbors have dysentery. He further mentions that a child of Johan Donat has died because of this.

Dysentery was a serious illness in the 1800s and was characterized by diarrhea with blood. Today, dysentery is commonly seen as symptom of Shigellosis – an infection with the Shigella bacteria. Shigellosis is typically transmitted through improper food handling (particularly foods that are raw or unpasteurized) or drinking water contaminated with sewage.

View from Hawk Mountain looking towards the Hagenbuch homestead. Donat’s Peak is the high hill visible on the left side of the image. Flickr/pwbaker

Johan Donat’s name is worth touching upon too. Not far from the Hagenbuch homestead is a tall hill known as “Donat’s Peak.” This prominent geographic feature was almost certainly named after the Donat family who lived close by.

Timothy goes on to mention that their brother Michael’s (b. 1805, d. 1855) house is not yet done. This house is still standing today and contains a cornerstone with the date 1851. Though unfinished in September of that year, Timothy states that the pointing on the house is complete, meaning that the mortar has been placed between joints in the stonewalls.

The letter continues by relaying news of another brother, Amos (b. 1808, d. 1868). Amos has put his land up for sale, even while his barn remains incomplete. His reasons for selling are straightforward. The land on his farm is poor and rough, the taxes are high, and he pays too much interest. It is fascinating to see how complaints from the mid-1800s sound similar to those so often heard today!

Timothy writes to Enoch that Amos never planned to go west in his lifetime. However, he changed his mind after his wife, Sarah (Bailey) Hagenbuch, started pushing to go. She wants to find better quality land that is cheaper than what can be had in Pennsylvania. According to the letter, Amos paid $3400 for 123 acres land and he hopes to sell it for $4000. Accounting for inflation, $4000 is equivalent to around $125,000 today.

During the 1800s, many Hagenbuchs made their living as farmers. A farm’s viability was closely tied to the price and the productiveness of the land. When Pennsylvania was first settled, land was cheap and plentiful; however things were changing as the state’s population grew rapidly. In 1800, Pennsylvania had around 3/4 of a million residents. By 1900, this had increased by 700% to six million people.

All of these people needed homes and a livelihood. As demand for farmland rose, so did prices. Eventually, land opportunities in less populated states began to look attractive and people moved west. In fact, all of Timothy’s brothers would leave Pennsylvania with the exception of Michael. He had purchased the Hagenbuch homestead after the death of their father, Jacob (b. 1777, d. 1842).

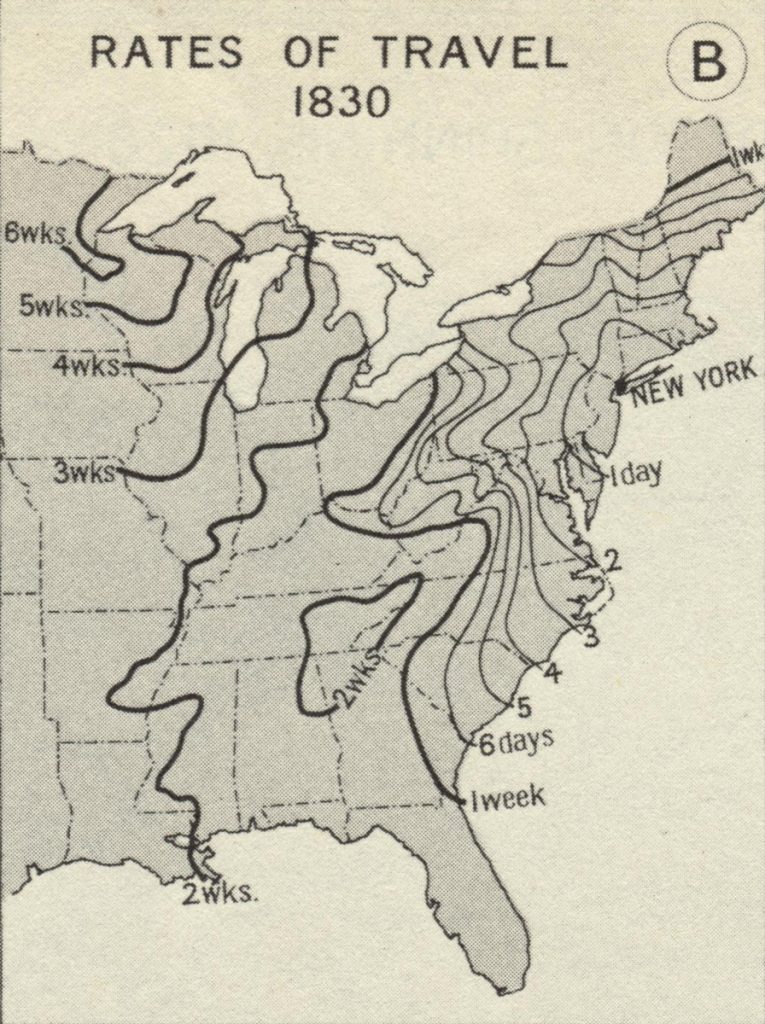

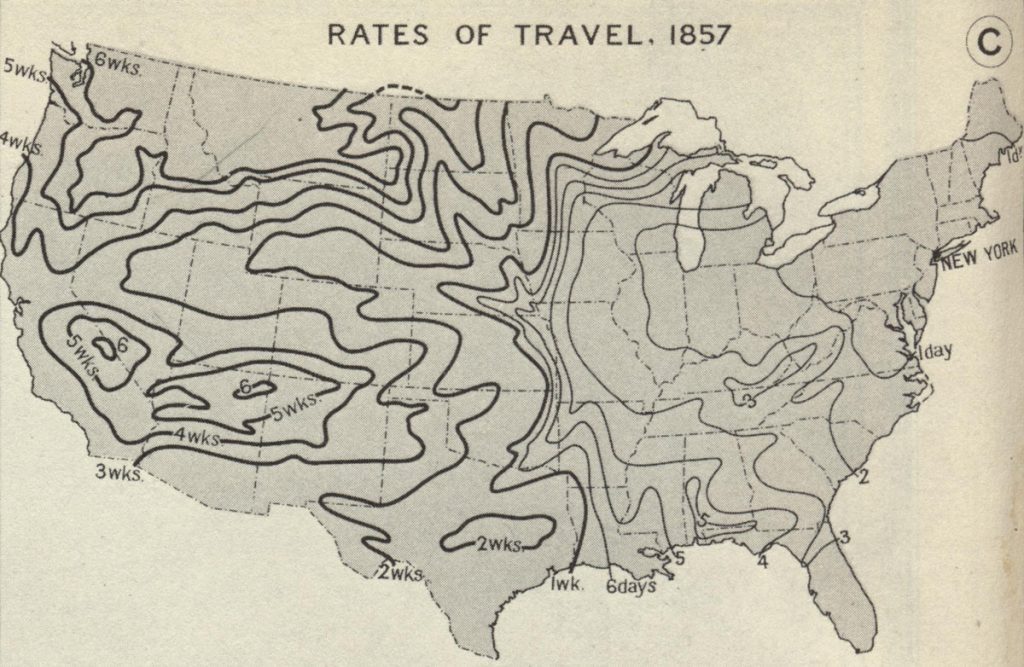

Traveling west was hardly a simple task, especially before the invention of the railroad. When Enoch went to Indiana in 1838, he traveled at least part of the way by horse and wagon. Per the above map, the fastest such a trip could have been made in was around three weeks. However, this assumes traveling light without a heavy wagon in tow.

Yet, by the 1850s the railroad was making westward travel significantly faster. Timothy describes in his letter that Amos will go west via the train. He mentions that another family took a similar journey via rail and water (likely a steamboat) and was able to complete the trip in only four days. This is a substantial improvement over the weeks it would have taken just a few decades earlier!

Enoch’s History of the Hagenbuchs in America also helps to tell the story of the family’s western migration. According to it, in early 1851 Daniel Hagenbuch (b. 1816, d. 1867) relocated from Indiana to Ottawa, La Salle County, Illinois near the Illinois River.

Timothy’s letter, written later in the same year, picks up from there. It reveals that now Enoch is considering moving, as are some of his brothers back in Pennsylvania: Amos, Charles (b. 1819, d. 1891), and Aaron (b. 1820, d. 1855).

However, as Timothy describes, Amos is concerned about the land near Ottawa. He has heard it is mostly prairie and that there are few trees. Amos, now 43 years old, doesn’t want to clear land anymore, so he wants a parcel that has already been developed. Finally, he requires good water, as that is more important than having the best land.

In the letter, Timothy says to Enoch, “…if you can find a good and reasonably priced area this fall then perhaps the brothers will move to your neighborhood; because they don’t want to go to Daniel’s [area].” It appears that he did exactly as was suggested.

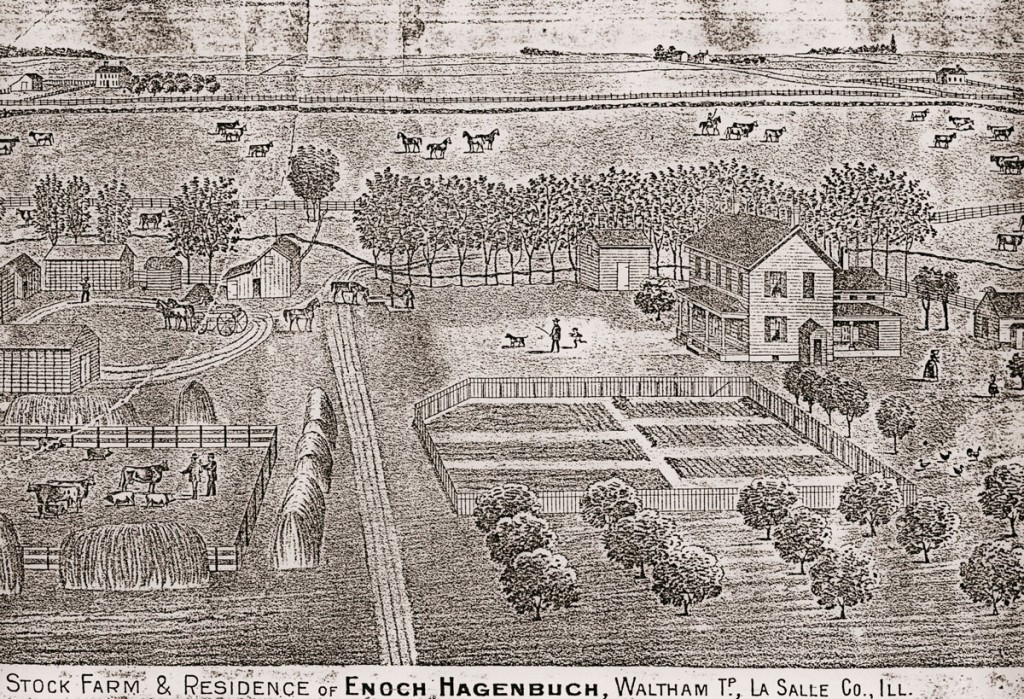

According to Enoch’s history, in the fall of 1851 he sold his farm in Indiana and traveled back to Pennsylvania. There he appears to have visited with his brothers Timothy, Michael, Amos, Charles, and Aaron and told them of the land he had found. In the spring of 1852, Enoch settled on his new farm in Waltham Township, La Salle County, Illinois, just a short distance from Ottawa where Daniel lived. Enoch paid $2000 for 160 acres, less than half of what land was going for in Pennsylvania.

Aaron and Charles moved to Waltham Township two years later in 1854 and Amos finally arrived in 1859. Based upon Timothy’s letter, they likely traveled by train to a major river city such St. Louis, Missouri. From there, they would have taken a steamboat up the Mississippi River to the Illinois River which could be navigated all the way to Ottawa, Illinois.

Other Hagenbuchs would come to Illinois too. Solomon Hagenbuch (b. 1831, d. 1873), Amos’s son, arrived sometime in the mid to late 1850s. Timothy appears to have had a fondness for his nephew and even left him money and books in his will. When writing to Enoch, he mentions Solomon’s recent marriage to Christina Schellhammer and jokes that the young man was “really too old” to be married. Solomon was 20 on his wedding day!

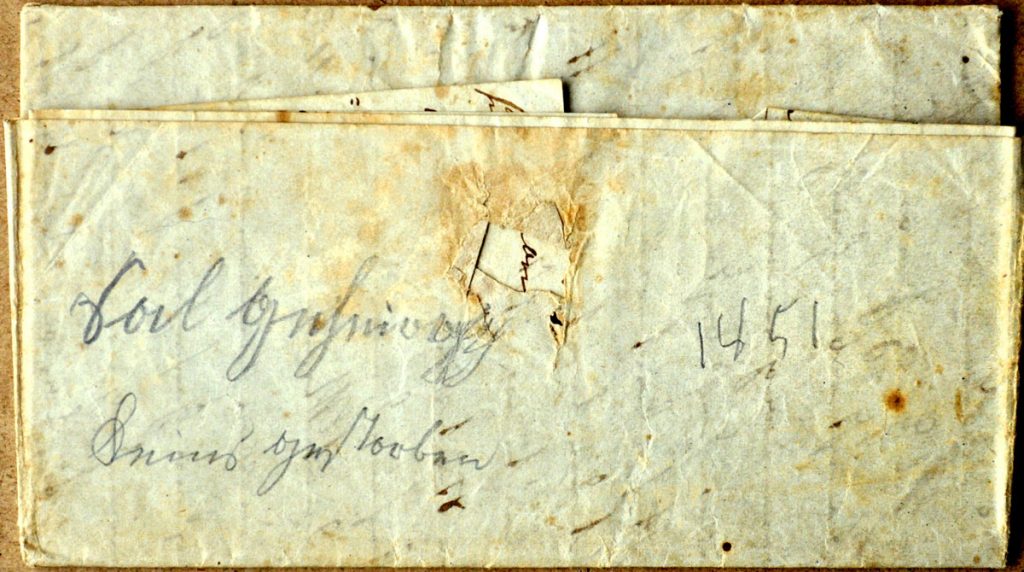

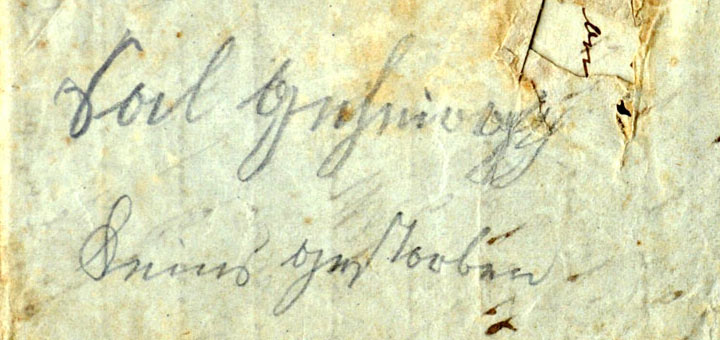

One final element of the letter worth noting is the penciled writing on the outside of it. This does not appear to be Timothy’s handwriting and, instead, could be Enoch’s. The text reads: “Sal married. No one has died. 1851.” One possible theory is based upon Enoch’s interest in family history. With a lifetime of correspondence in his possession, a few quick notes on the outside of a letter might have made it easier for Enoch to later locate information about specific family events.

Timothy’s 1851 letter to his bother, Enoch, is an exciting window into the lives of Hagenbuchs during the mid-1800s. Not only does it reveal important relationships, but it also provides crucial insights into the reasons family members left Pennsylvania and headed west.