Thoughts on Timothy Hagenbuch’s 1839 Letter to Enoch

In August of 1839, Timothy Hagenbuch of Albany Township, Berks County, Pennsylvania sent a letter to his brother, Enoch, who was living in the town of Muncie, Delaware County, Indiana. This wonderful letter was found by Zac Bow and donated to the Hagenbuch family archives earlier this year. At around 1500 words, Timothy’s letter includes a great deal of family news, local events, and other information to sift through.

The identities of some of the people mentioned in the letter are not immediately clear. One of these is Joseph—last name not provided. Timothy writes that he hopes Joseph will read the letter, indicating that he was a close family friend or relative. Joseph is mentioned at other places including here:

Amos Grünewalt has in mind next spring to take Neifert’s place. Samuel told me in April [his] father would like to see where you and Joseph live, that is, your land.

. . .

Is Joseph still single? How did his court case turn out? And how is Joseph coming along? Does he already have a house on his land?

In 1835, Enoch married Christina Greenawalt (also spelled Grünewalt), whose older brothers included Amos, Samuel, and Joseph. So, Timothy is referring to Joseph Greenawalt, Enoch’s brother-in-law. Research reveals that Joseph relocated to Indiana around the same time Enoch did and that he also settled in Delaware County. He eventually married too. The 1850 census shows Joseph Greenawalt, age 42, living with his wife Nancy and their four children: John, Joseph, Amos, and Samuel.

Another person Timothy writes about is Enoch’s father-in-law, Johan Greenawalt, whom he calls “Old Johan.” He describes how Johan wants to send Enoch some money and explains several ideas for how to get the money from Pennsylvania to Indiana. He also mentions that Johan paid the 25 cents postage to send the letter.

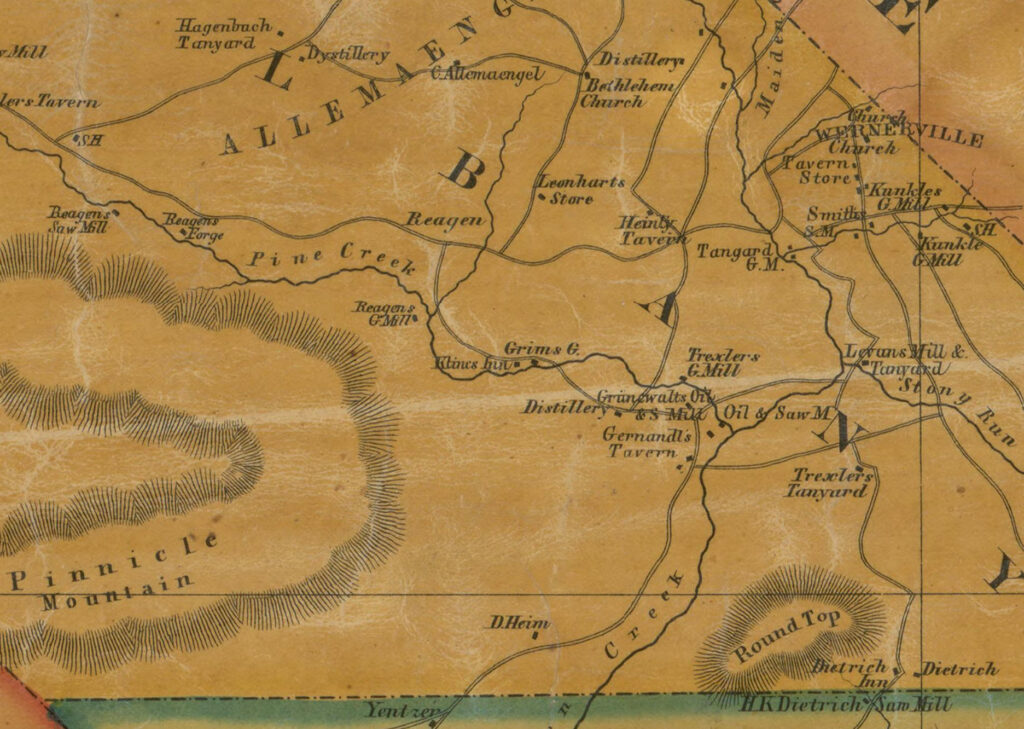

Portion of an 1854 map of Albany Township, Berks County, PA. The Hagenbuch Homestead/Tanyard is located in the top left; Greenawalt’s is to the right of the Pinnacle Mountain; and Dietrich’s is just below Round Top Mountain in the lower right.

A bit of searching uncovered that Johan Greenawalt was an interesting character. According to the book Historical and Biographical Annals of Berks County, Johan (b. 1784) was married three times and lived at the foot of the Pinnacle—a mountain—in Albany Township. There, he farmed a sizable tract of land and operated an applejack distillery. Rumor has it that he was quite wealthy and that he kept a large bag full of gold and silver coins under his bed.

Timothy’s references to Old Johan’s money seem to support this fact. They also help to explain why “storekeeper Kamp” was mad at Johan for not loaning him any money. Timothy writes:

Jesse [Zähner] loaned the storekeeper Kamp $200, Schneider $70, Daniel Z. $80. That was their inheritance, and maybe they will not get the money [back] during their lifetimes. Kamp’s window was broken on June the 14th, 15th, and 22nd; on July 12th, 13th, 19th, and 20th; and on Aug 2nd, 3rd, 10th, 16th, and 17th day. Kamp’s debts are said to be 6 to 7 thousand dollars. Kamp also wanted to get money from your father-in-law [Johan Greenawalt], but he gave him none. That made Kamp mad.

The location of Kamp’s store (also spelled Kemp) is unknown. One clue is the village of Kempton, which is located not far from where the Hagenbuchs lived. It could be that the Kamp family lived near that spot in the early 1800s. Regardless, Timothy’s letter reveals that a number of people in the area were angry at Kamp for not repaying his debts. This led them to break his windows—likely those of his store and home—on 12 different occasions.

Timothy goes on to discuss some news from Jacob Dietrich, who apparently was married to Leah and lived with his father, “Old Dietrich.” Research shows that Jacob Dietrich (b. 1813) was married to Leah Greenawalt (b. 1817), the daughter of Johan Greenawalt and sister-in-law of Enoch. Jacob’s father, Old Dietrich, was Johan Jacob Dietrich (b. 1773).

According to the Historical and Biographical Annals of Berks County, Johan Jacob Dietrich was a large landholder, operated Dietrich’s Hotel, had an applejack distillery, and ran a tannery. Timothy mentions that he had heard from Samuel Greenawalt that “Old Dietrich did not want to let [his son] move.” A bit of digging reveals that Jacob and Leah Dietrich did, indeed, leave Albany Township.

Leah’s obituary from 1903 describes how she and her husband, Jacob, moved to Muncie, Indiana in 1840—only a year after Timothy’s letter was written. After living there 18 years, they moved again in 1858, this time to Lyon County, Kansas near the town of Emporia.

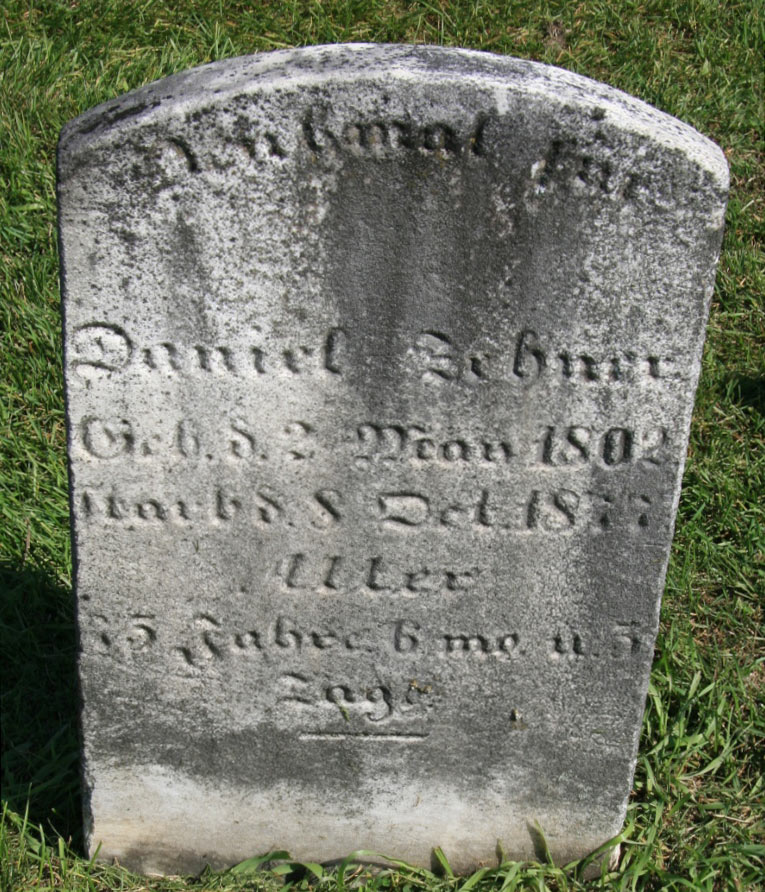

In addition to the comings and goings of locals, Timothy writes about the misadventures of Daniel Zehner (Zähner):

[Daniel] Zähner ran away the 28th of January because of Rebecca Koch. On February 14th he came back. He was at the Wertmans’. On March 7th the constable caught him and took him to Esq. Halteman. He married them. Daniel does not live with her. At Pentecost, he had it put in the newspaper [that] she has a daughter.

It does not appear that this shotgun wedding led to a long-term commitment. Little can be found about the life of Daniel Zehner (b. 1802), though the 1850 census shows him unmarried and working as a shoe carpenter. He is buried at New Bethel Church in Albany Township without any mention of a spouse. The church’s records provide one additional fact. The Wertmans referenced by Timothy may have been his baptism sponsors—John and Maria Wertman.

Family news is also included in the letter, and Timothy provides a few details about his brothers Michael (b. 1815) and Amos (b. 1808). He writes that on March 25th, Michael had a son, Nathan D. B., whose baptism sponsor was Daniel Bailey (Böhly). This information suggests that Nathan’s middle initials, D. B., stood for Daniel Bailey.

Timothy goes on to tell Enoch that Michael and Amos are distilling along the Schuylkill River. It is known that the Hagenbuch family was involved with distilling and likely had a distillery at the homestead. Yet, by the mid-1800, small distilleries were on the decline. Therefore, it seems possible that Michael and Amos had hired themselves out to a larger distillery located near Hamburg and Reading. Both towns are located along the Schuylkill River.

Along with information about people, Timothy spends some time discussing the prices fetched by various crops such as rye, corn, oats, and peanuts. He also discusses the availability of silver in this curious passage:

In Sept and Oct 1838 the Schinnblästers ran out. Silver is at this time more plentiful than in 10 years.

When beginning to research this, it was thought that Schinnblästers were a family who had left the area. However, translator Jean McLane suggested that it might actually be a transliteration of the word shinplasters.

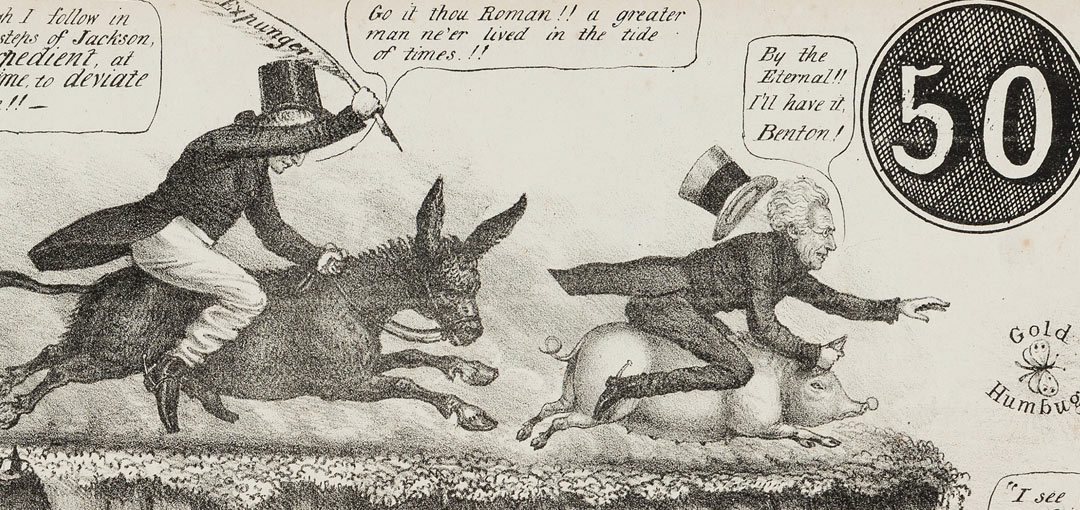

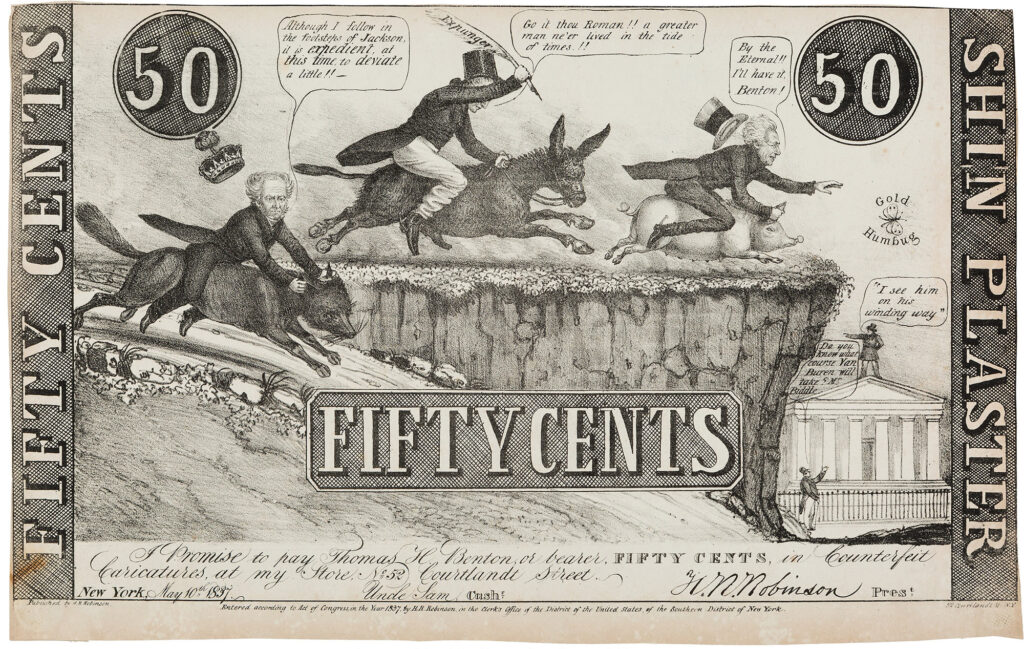

Parody of a shinplaster from 1837. It depicts Martin Van Buren riding downhill on a fox, Andrew Jackson riding a pig and chasing the Gold Humbug, and finally Thomas Hart Benton riding a jackass urging on Jackson. They are headed off a cliff.

Shinplasters were paper money that increased in use after the Panic of 1837—an economic crash that threw the United States into a depression. Due to a lack of gold and silver coinage in circulation, banks and other entities began to issue paper bills in small denominations. The public often distrusted these paper notes and believed they had little intrinsic value. The bills were dubbed shinplasters, referencing a worthless piece of paper used as padding between one’s shins and their boots.

The History of Reading, Pennsylvania describes the rise of shinplasters in Berks County:

A money panic arose in the borough in 1837, owing to a suspension of prominent banks in the large cities, but the local business men published a notice in which they expressed entire confidence in the Reading banks and a willingness to accept their notes in payment of debts and merchandise. But the scarcity of money compelled certain merchants to resort to an expedient for a circulating medium by issuing notes for small sums which were called by the people “Shinplasters,” “Rag Barons,” and “Hickory Leaves.” And the Borough Council, to relieve the community in this behalf, issued loan certificates in denominations of 5, 10, 25, and 50 cents, and 1, 2, and 3 dollars.

In the letter, Timothy is updating Enoch about the low supply of paper money, shinplasters, in Albany Township. He is also describing how silver coinage is becoming more available—the most they have seen in 10 years.

Without telephones, email, or social media, letters were one of the only ways a family, increasingly spread out across the country, could stay in communication. The fact that letters like this one were saved is a testament to their value. They weren’t simply read and discarded. Rather, they were carefully preserved and archived, something we continue to benefit from today.

Many thanks to Jean McLane for his work in translating the letter and Joshua R. Greenberg for his insights into shinplasters and currency of the time. To learn more about shinplasters, check out Greenberg’s book: Bank Notes and Shinplasters: The Rage for Paper Money in the Early Republic.

Thank you Andrew….more good information….don’t take any wooden shinplasters!!!!