Thoughts on Jacob Hagenbuch’s Estate Inventory

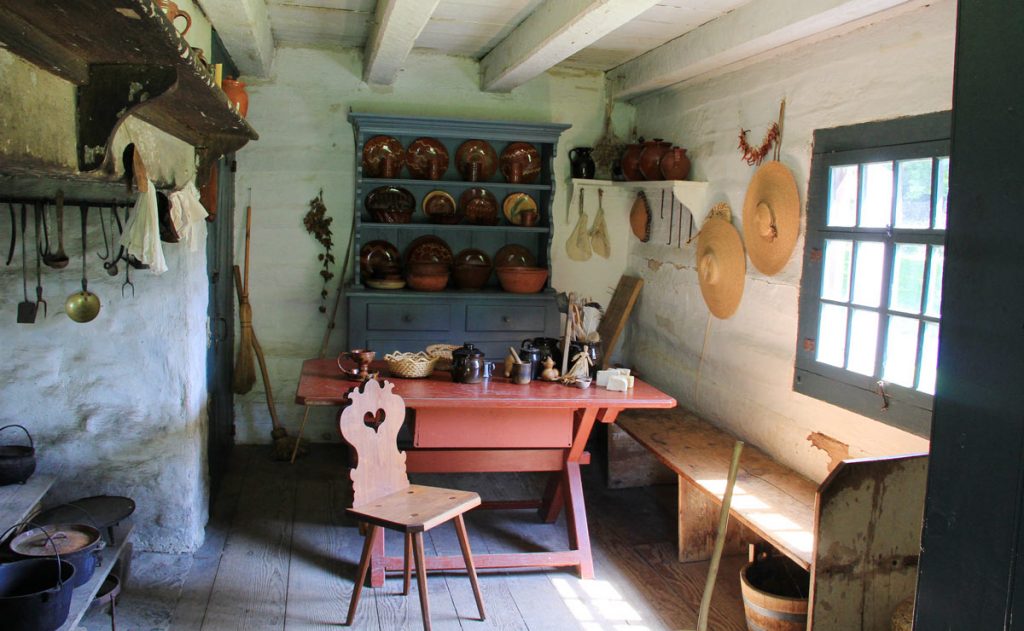

Jacob Hagenbuch died in 1842 at the Hagenbuch homestead in Albany Township, Berks County, Pennsylvania. He left no will, forcing a local judge to order that his entire estate be inventoried. The contents of the inventory document were translated from Deitsch and presented in a previous article.

Historical records often leave many more questions than answers. Knowing someone owned a thing does not reveal why it was kept or how it was used. Complicating things further, items are sometimes listed in outdated or colloquial language.

To help answer questions raised while researching Jacob’s inventory, we sought the advice of experts in Pennsylvania history and Deitsch culture. Many thanks to Chris Witmer, Patrick Donmoyer, Mark Turdo, and Sam McKinney for their valuable insights.

Value of the Estate

Jacob Hagenbuch’s estate (minus any landholdings) was valued at approximately $1,558. When adjusted for inflation, this is equal to around $46,000 today. The moderate sum places the value of Jacob’s estate below that of his father, Michael (b. 1746, d. 1809), whose estate was valued at about $60,000. The disparity is even larger when comparing Jacob to his grandfather, Andreas (b. 1711, d. 1785). His estate was worth nearly $200,000 at the time of his death.

Several theories might explain why the value of the homestead declined over time. The first is that Jacob had begun the process of retiring. Indeed, many of the tools and animals, like horses, needed to work the land he owned are missing from the inventory. It could be that Jacob had sold some of his estate, possibly to one of his sons. Supporting this idea, an auction bill (money owed to Jacob after selling merchandise at an auction) can be found in the inventory document.

Another theory is that the family businesses, such as textiles, distilling whiskey, and tanning leather, were becoming less profitable. By the early 19th century, industrialization was well underway in the United States. Mechanized methods for producing textiles were drawing people away from home-based operations to more profitable factories in cities. In addition, increased cotton production in the American south dented demand for flax and, as a result, linen.

Linen & Wool

Even with a changing economy, Jacob Hagenbuch’s inventory reveals that textiles were still an important part of the family’s income. The document lists flax, wool, spinning wheels, and a loom – all of which were necessary to produce linen and wool fabrics.

The inventory also reveals how the flax plant was turned into thread to weave linen. First, an item called a “flax break” was used to break the tough flax stalks and reveal the usable fibers. Next, a “scutching mill” would process the flax and remove the bits of stalk from the fiber. Finally, “hackles,” which looked like metal combs, were employed to straighten out the fibers ready to be spun into thread.

According to the inventory, the flax may have been used to weave a fabric called satinette. Unlike true satin, which is made from silk, satinette blends cheaper fibers, such as cotton and wool, to create a glossy, satin-like appearance. Jacob may have been using linen, instead of cotton, to produce satinette at the Hagenbuch homestead.

Distilling

While Jacob’s inventory mentions a still, cap, and coil for use in distilling spirits, there was little finished product on hand. In fact, only one barrel of “cider royal” is listed. Research shows that cider royal was once a popular drink, created by blending fully fermented cider with apple brandy and a sweet, simple syrup.

Compared to his father, Jacob appears to have been less focused on distilling. His still was worth little, perhaps because it was small or damaged, and he had only a small amount of alcohol stored.

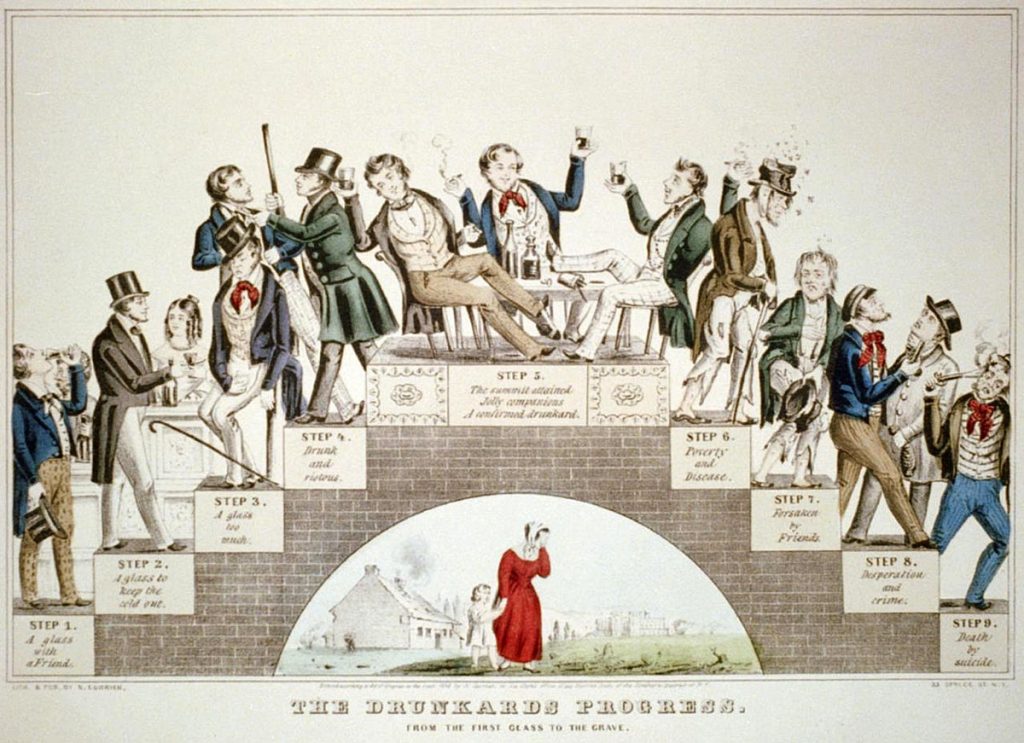

It should be noted that temperance was on the rise in the United States. By 1838, only a few years before Jacob’s death, the American Temperance Society claimed to have over 1.2 million members – almost 8% of the country’s population! With the consumption of alcohol falling out of fashion, it could be that the Hagenbuchs were turning away from distilling.

Leather & Butchering

Also like his father, Jacob Hagenbuch was a tanner and worked with leather. Evidence for this can be found in his inventory, including an amount of leather, calf hides, and other tools used by tanners. Cuts of meat are listed too, as well as equipment for making lard and sausages.

When considered altogether, it appears that the Hagenbuch homestead had a business of butchering livestock. The meat was processed and sold, as were the hides. The number of calf hides listed is especially telling. Local farmers may have brought their calves to be slaughtered in order to produce veal and valuable calfskin leather.

Agriculture

Jacob Hagenbuch owned over 300 acres of land. Some of this was mountain land, which was used to quarry stone, gather timber, and provide the bark necessary for tanning leather.

The rest of the land was flatter and almost certainly cultivated a variety of crops. The inventory gives an idea of what these may have been, including flax, buckwheat, clover, oats, potatoes, sugar beets, and corn. Livestock were kept too; cows, hogs, and sheep are all listed in the document.

Other Items

The inventory notes a number of other fascinating items. For example, a “fowling piece” is mentioned. This refers to a smooth bore gun, which was similar to a shotgun and probably had a flintlock firing mechanism. It is the first firearm found in a Hagenbuch estate inventory. Jacob also owned both a “pleasure carriage,” which is an open topped buggy to be pulled by a horse, as well as a “pleasure sleigh” to be used in the winter.

A “washing machine” appears on the inventory too, though this was nothing like a modern laundry washing machine. Instead it was probably a simple, hand operated device used to clean produce or something else on the farm.

Jacob held a variety of personal effects such as books, a small telescope, a pocket watch, and a 24 hours clock in a case. Yet, it is the last item on his inventory which has caused some of the greatest speculation – a “twenty dollar note from the Commercial Bank of Florida.”

In 1842, Florida was still a territory of the United States and nearly 1000 miles away from the Hagenbuch homestead. One can only wonder, why did Jacob have a $20 bill issued by a bank in Florida? Did he acquire it from a traveler passing through Pennsylvania? Or did he, perhaps, do business with someone located in the territory? Once again, as is so common with historical documents, one is left with a fuzzy picture of the past that provides as many questions as it does answers.

If you have any thoughts as to why the Hagenbuch family may have held a $20 Florida banknote in 1842, please leave a comment below or on Facebook!