Thoughts on Andreas Hagenbuch’s Last Will and Testament

On April 9, 1785 Andreas Hagenbuch signed his last will and testament (Read: Andreas Hagenbuch’s Last Will and Testament). He died sometime between April 11th and September 26th of that year and was buried at the Hagenbuch homestead in Albany Township, Berks County, Pennsylvania. He was 70 years old.

Andreas’s will is a fascinating document. It provides important insights into the family, their most valued possessions, and their relationships with one another. For example, Anna Barbara Hagenbuch, the eldest daughter, is willed more than the others:

… something more ought to be given to my daughter Anna Barbara, as I have herein bequeathed to her because she is unhealthy …

The will makes it clear that she had a health problem, which moved Andreas to give her an additional sum of money:

… I give and bequeath to my above mentioned daughter, Anna Barbara, the sum of 140 pounds good gold or silver money which my executors shall pay to her … she shall likewise have one good bed, my kitchen furniture, my chests, 1 cow and 1 heifer, with that what my beloved wife, Maria Margaretha, shall further give her, as she finds good, because she is in want of it.

Anna Barbara received more than just money. She was willed furniture and livestock – valuable items in the 18th century. Andreas even left open the possibility that his wife might give Anna Barbara more as needed. This raises a number of questions. Was Anna Barbara married and, if so, why was her husband without the means to care for her? A future article will dive more into the theories surrounding her life.

Similar to her older sister, Magdalena is given an extra amount of money (10 pounds). This time, the additional money is given “because she has faults in her eyes”. It shows that Andreas carefully considered the situation of each person mentioned in the will, giving more to those who needed it.

As a father, Andreas provided something for all of his children, though this was often done in a unique way. For instance, if a child owed him money, he deducted the debt from the willed amount:

… I give and bequeath to my son, Henry Hagenbuch, to the debt of 20 pounds and 3 shillings which he owes to me in my book, yet the further sum of 79 pounds and 17 shillings good gold or silver money, which my executors shall pay to him or his heirs as follows: 29 pounds and 17 shillings on the 27th day of November in the year of our Lord 1785 and 50 pounds on the 27th day of November in the year of our Lord 1793, wherewith he gets together 100 pounds and he shall further have no right, no ways to make any other demand on my other remaining estate, because a father has his will to make his testament as he pleases …

Here, Andreas leaves Henry 100 pounds minus the debt he is owed. Interestingly, he distributes the money in two payments, separated by eight years. This may have been done to ensure some money remained in his estate until his wife died.

The last line also reveals something about Andreas’s relationship with his son. He specifically states that Henry shall have nothing further from the estate. Henry, as the eldest son, may have felt entitled to a portion of the homestead or additional money. He received neither.

One can only speculate about the relationship between father and son. Henry lived and worked on the family farm for many years. However, sometime before the Revolutionary War, he moved to Allentown, Pennsylvania and established a tavern there. His connection to the family may have changed as a result.

Henry, like most of his siblings, received 100 pounds from his father. Comparing money in the 18th century to that of the 21st century is not an easy task. However, a rough estimate values the amount at between $15,000 and $20,000 today.

The will shows that Andreas Hagenbuch was certainly not a poor farmer. He distributed around 1000 pounds between his children and grandchildren. On the high end, this would be worth about $200,000! Furthermore, the sum doesn’t account for his possessions, livestock, or land. While Michael and Christian divided the land, the youngest son, John, received something entirely different:

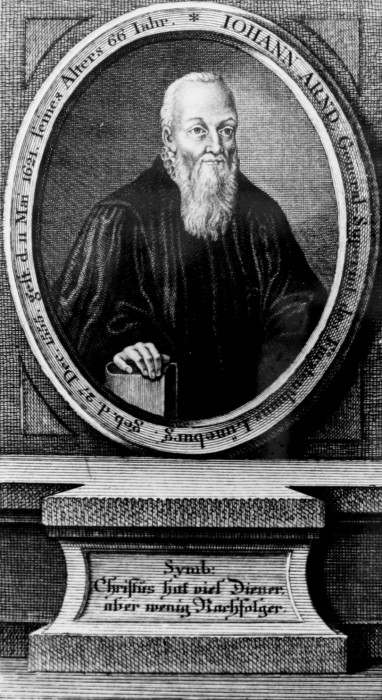

… I give and bequeathed to my son, John Hagenbuch, the sum of 150 pounds good gold or silver money, which my executors shall pay to him or his heirs … and he shall have the book called Johann Arndt’s, Verily Christiandum.

Books were highly valued in the 1700s, and this one, known in English as True Christianity, undoubtedly held great value to the family as evidenced by its mention in the will. The Lutheran theologian, Johann Arndt published True Christianity in the early 1600s. It featured writings on the mystical relationship between a believer and Christ, as well as provided guidance on living a Christian life. Along with this book, John received 50 pounds more money than his older brother, Henry.

Two of Andreas’s grandchildren are mentioned in the will. These are Magdalena Brobst, daughter of Catharina “Hagenbuch” Brouss and John Schisler, son of Maria “Hagenbuch” Schisler. Andreas splits money between each grandchild and their mother. Possibly this was done because these grandchildren provided help on the family farm.

One of the most interesting pieces of information found in Andreas Hagenbuch’s will relates to the dividing of linens. Before the widespread use of cotton, many textiles were made of linen. This was produced from the flax plant and was used to make everything from bedding to clothing.

… what concerns the white linen goods, that the said Maria, Magdalena, Anna Elizabeth, Christina, Anna Margaretha, Anna Barbara, and Magdalena Brobst, shall share the same in 7 equal shares and rough cuts …

Flax could be grown on a farm, and it is likely that the Hagenbuchs planted it. After harvesting, the women in the family would spin and weave the fibers into linen “rough cuts”. These could be used to create finished linen goods. Linen fabric would have been valuable, and from the above, the Hagenbuch homestead appears to have a been a substantial producer of it.

Andreas Hagenbuch signed his last will and testament on April 9, 1785. Two days later on April 11th he created a codicil clearly mandating that 490 pounds remain with his wife until her death. Only then would the remaining money be distributed. Today, this document serves as an important record for the Hagenbuch family. Through it, one is able to peer into the past and gain a better understanding of the Hagenbuchs in the 18th century.

This article was updated in 2022 to reflect that Magdalena Brobst was the daughter of Catharina (Hagenbuch) Brouss and she had taken the name of her husband, Jacob Brobst.