There’s More to the Story

Our Hagenbuch genealogy remains a work in progress. Look back at this site’s earliest articles and you will likely find an inconsistent detail or unfinished story. When my father, Mark, and I first began working together in 2014, we were primarily concerned with documenting what we already knew about our family. As time went on, we realized that much of this information needed additional research and investigation. The process of refinement and discovery continues right up to the present day.

Case in point: I was recently pondering the untimely death of Lawrence J. Hagenbuch, who was the younger brother to my grandfather, Homer S. Hagenbuch (b. 1916). Lawrence was born February 23, 1921 and died December 11, 1922 shortly before his second birthday. As recounted in a previous piece, Homer recalled the following about Lawrence:

Mom [Hannah (Sechler) Hagenbuch] was hanging out wash, and I was watching Lawrence crawling around on the ground. Once in a while he would pick up chicken dirt [feces] and put it in his mouth. I never told Mom about it. I wonder if that’s why he died? I should have told Mom about it.

In the article, my father suggested that Lawrence may have been a sickly child, since he was baptized shortly after being born. This shifted the blame away from my six-year-old grandfather, who was only six years old at the time. Still, I couldn’t stop thinking about the story and wondering what had killed young Lawrence. Maybe my grandfather had misremembered the whole thing?

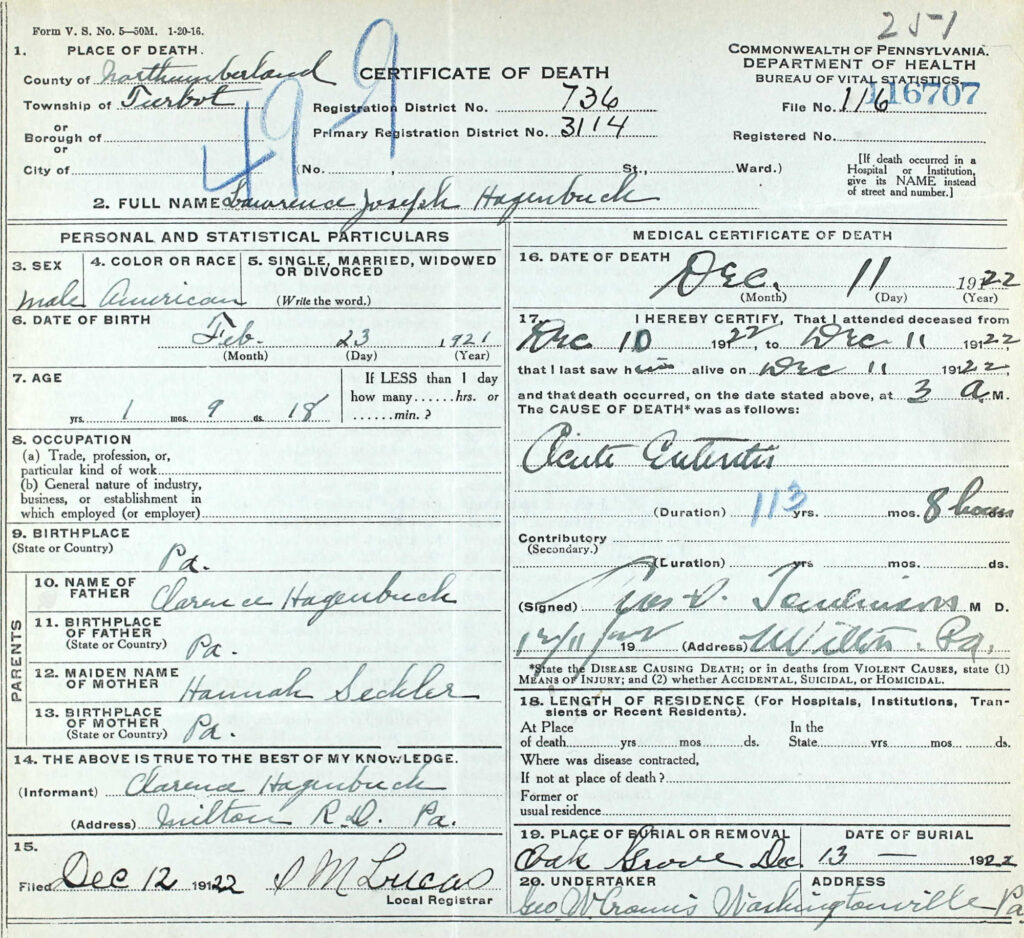

Since the turn of the 20th century, most states have issued death certificates for their deceased residents. I searched for Lawrence Hagenbuch’s and found it on Ancestry. According to the document, Lawrence died of “acute enteritis” after being treated by local physician, Dr. Charles S. Tomlinson of Milton, Pennsylvania.

Enteritis is an inflammation of the small intestine, caused by either a viral or bacterial infection. It can result in diarrhea, dehydration, organ failure, and death. It is possible that Lawrence consumed food or drink that contained a pathogen, such as a rotavirus. Rotavirus infections can be especially serious in young people, which is why children are vaccinated against it today.

Salmonella and campylobacter are two other pathogens that frequently cause enteritis. Both bacteria live in the digestive tracts of poultry, like chickens, and can result in life-threatening infections in humans. This fact supports the idea that Lawrence ate chicken feces before dying.

Even so, other elements of the story paint a more complicated picture. Homer states that his brother, Lawrence, was crawling. At nearly two years old, it seems more likely that Lawrence was toddling or walking. Also, he died in December, when it was cold outside. Was there snow on the ground and would their mother, Hannah, have been hanging out laundry then?

It seems possible that my grandfather, Homer, was conflating different memories from his childhood. In the first, he watched his little brother, Lawrence, crawl in the dirt near his mother while she hung laundry. In the second, he heard an adult suggest that the boy took ill after eating tainted food or dirt from the ground. We now know more about Lawrence—he died of enteritis—although the source of his infection remains in question.

Another story that has resurfaced with more detail is the military service of Stephen Hagenbuch (b. 1828). For decades, his place on our family tree was the subject of speculation. We finally determined that he was the son of Henry II and Elizabeth (Göbel) Hagenbuch, a fact later confirmed in a Sunday school book kept by his younger brother, Henry III (b. 1833).

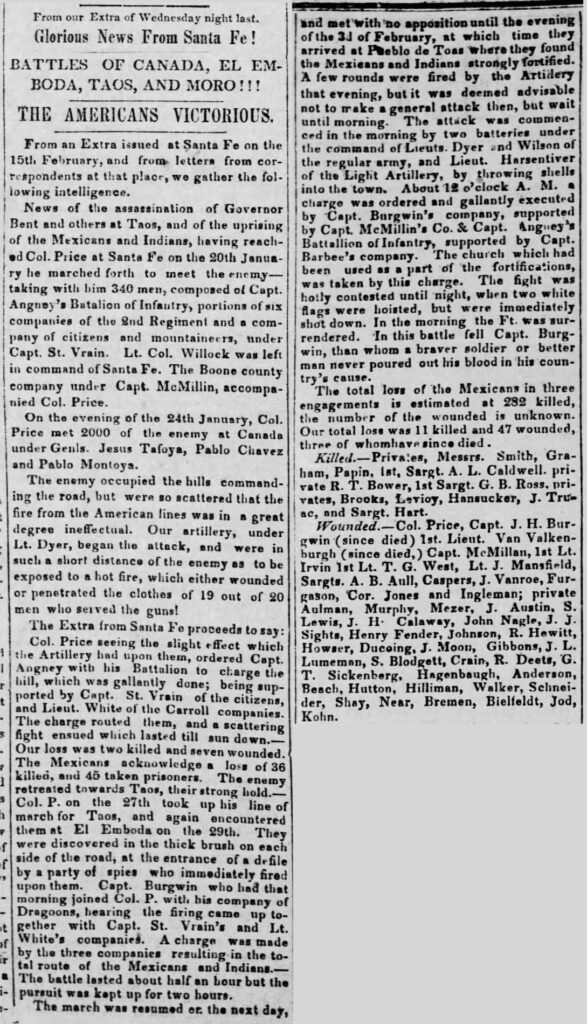

We already knew that on February 6, 1846 Stephen enlisted in the United Stated Army, 1st Dragoons, Company F to fight in the Mexican-American War. Dragoons were trained to fight on horseback and on foot. They were armed with Hall’s carbines or musketoons, dragoon sabers referred to as “old wrist breakers”, and horse pistols. Yet, little else was known about his service.

Excerpt from an article in the Columbia Herald-Statesman, April 9, 1847. Stephen Hagenbuch is listed under the wounded as “Hagenbaugh” near the bottom of the second column.

That changed when a newspaper article from the Columbia Herald-Statesman was discovered. According to a piece published on April 9, 1847, a soldier named “Hagenbaugh” was wounded in one of the battles that resulted from the Taos uprising in northern New Mexico. American troops had occupied the territory of New Mexico since August of 1846 after the Battle of Santa Fe. In January of 1847, Mexicans and their Pueblo allies led a revolt against the Americans within the territory. Several battles ensued, leading to casualties on both sides.

Stephen Hagenbuch appears to have been one of those wounded, and this event helps to explain why on May 3, 1847 he was honorably discharged at Albuquerque, NM. After the war, he made a full recovery and settled in Springfield, Ohio where he found work as a carpenter. He married Rose Anna Hilbert (b. 1832) and the couple had nine children together.

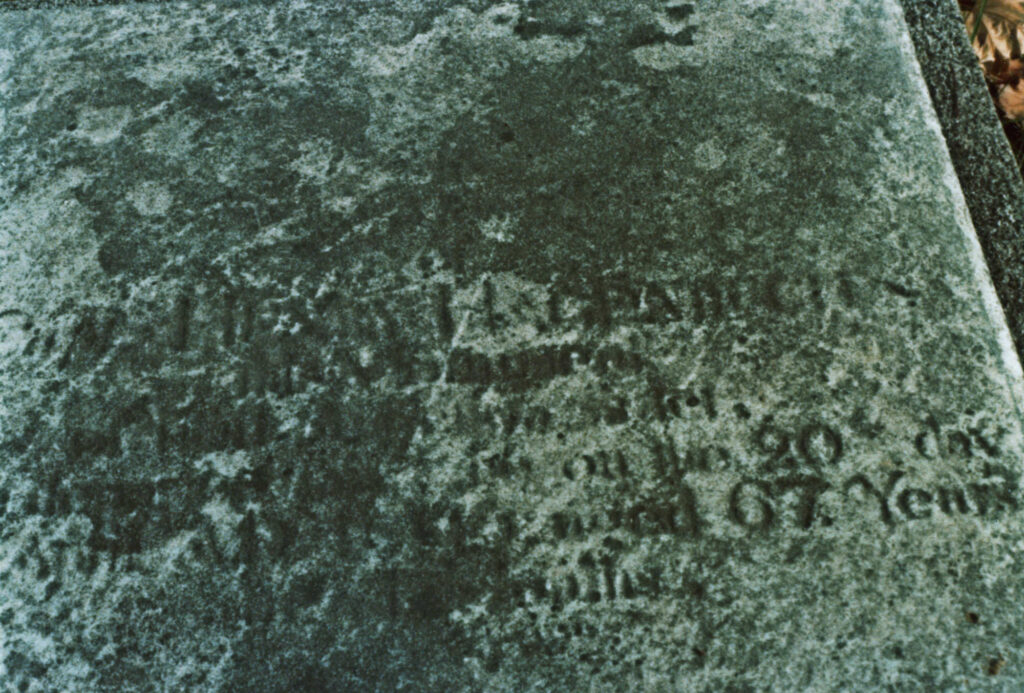

There is one, final story with more to discuss. This relates to Stephen’s grandfather Henry Hagenbuch (b. 1737). For decades, it was believed Henry was born in 1736, the year before his father Andreas (b. 1715) emigrated to the Pennsylvania Colony in 1737. A prior series of articles explored why Henry’s birthdate was probably December 20, 1737, after his parents arrived in America. One of the articles included a photograph of what was believed to be Henry’s weathered gravestone in the Old Allentown Cemetery.

A few weeks ago, my father was going through his old genealogy books when he made an exciting discovery—a picture of Henry Hagenbuch’s grave that was taken in the 1970s. Although tough to read, it was clear from the writing on the stone that this was Henry’s final resting place. I compared my father’s image to mine and realized that they were different!

I had assumed the stone I had photographed was Henry’s because it was located beside the grave of his wife, Susanna (Wettstein) Hagenbuch (b. 1743). Now it appears that he is buried some distance away in a grave that I could not discern as his.

Looking at my father’s image of the stone, it seems the marker was already badly weathered in the 1970s, explaining why the year he died is so difficult to know for certain. In fact, it is only possible to read that “Capt. Henry Hagenbuch” died “on the 20th day of April A.D.” and that he was “aged 67 Years.” The rest has been worn away. While disappointing, the newly found image enhances our knowledge of Henry and enables us to visit his gravestone in order to pay our respects.

In genealogy, like with every history, there is always more to the story. As my father and I reflect upon nearly 10 years of collaboration on Hagenbuch.org, it’s important to remember that the story of our Hagenbuch family is a living thing. As our understanding of the past grows, so does our knowledge of each person, place, and moment within it.