The Book, Part 4

This is the fourth in a five part series about “the book” owned by Andreas Hagenbuch (b. 1715). At the end of Part 3, the immigrant Andreas Hagenbuch has died and willed the book, Wahren Christentum (True Christianity) by Johann Arndt, to his youngest son, John (b. 1763). More than sixty years have gone by, and the year is 1847. John Hagenbuch died the year before. His youngest son Charles (b. 1811) is now the main character in the story.

The Book, Part 4

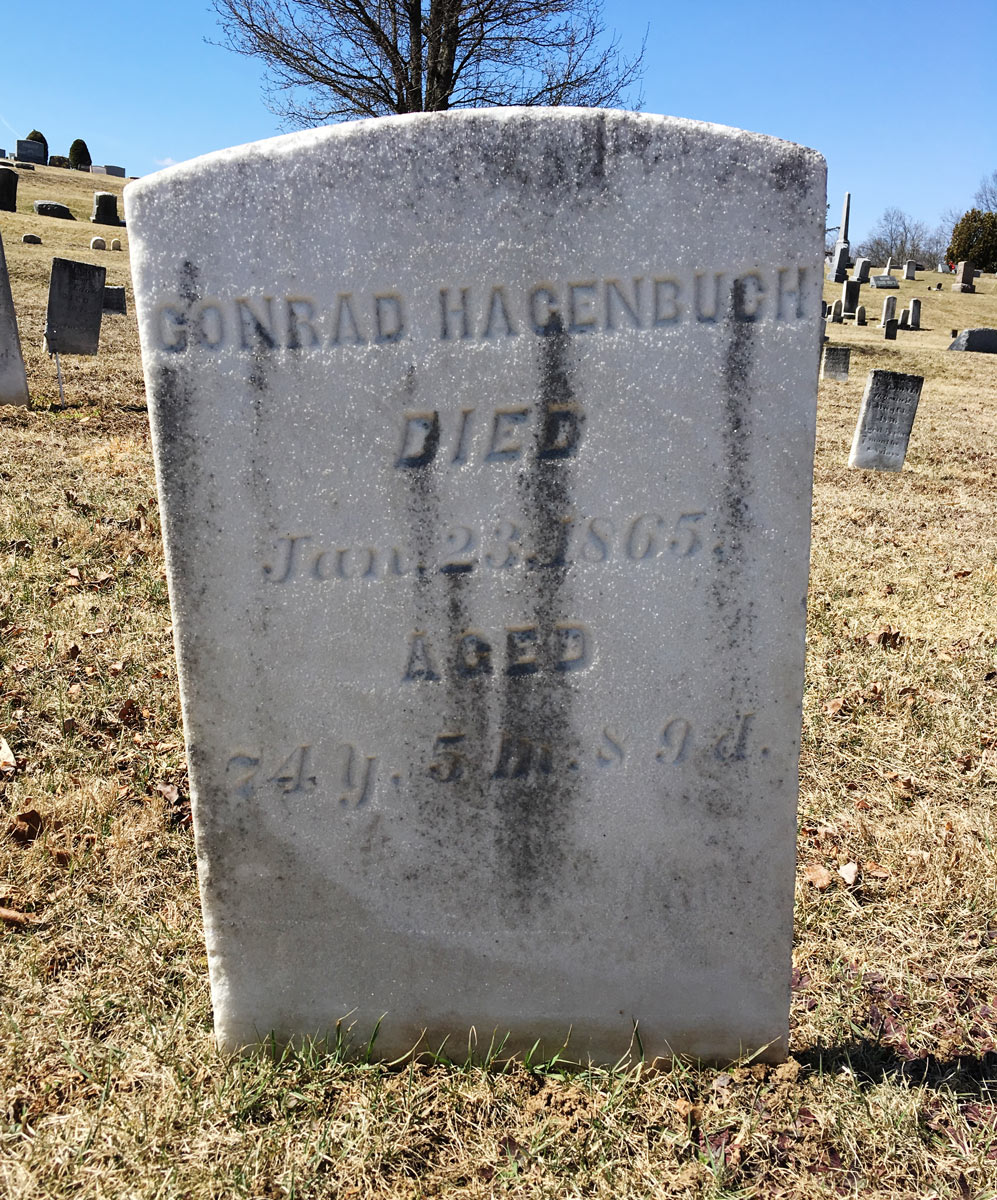

Charles Hagenbuch looked over the small piece of land he had purchased in Delaware Township, Northumberland County, Pennsylvania. His older brother Johann, who was called Conrad, lived nearby next to where the Delaware Run flowed. When their father, John, had died the year before, Charles had decided to move from the Hidlay Church area to be close to his favorite brother, Conrad, and Conrad’s son, John Phineas. Charles’ and Conrad’s six other brothers still lived near Hidlay in Columbia County where a few of them farmed what remained of the 500 acres which their father John had owned.

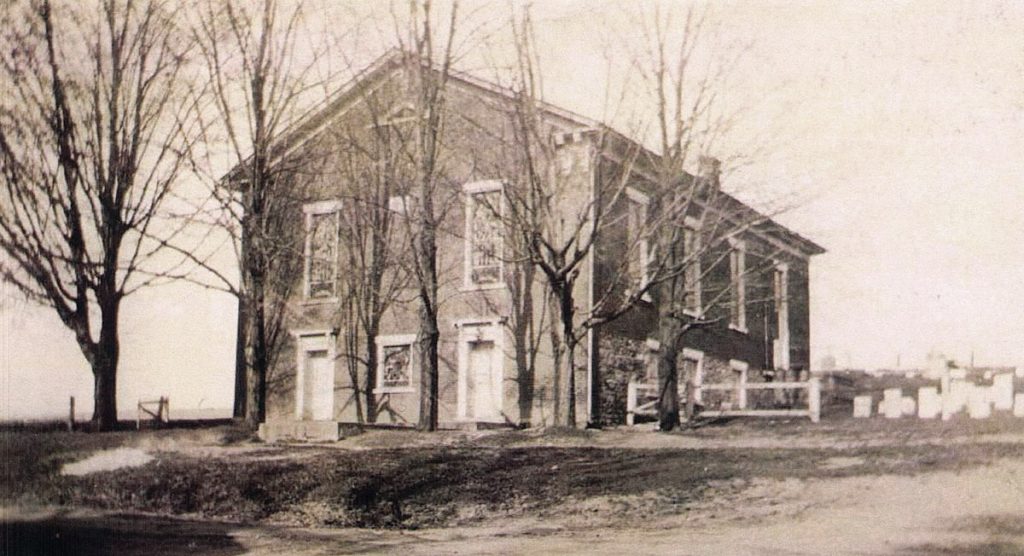

Charles’ reason for moving to Delaware Township to be near his brother Conrad was simple. Charles was a blacksmith by trade. Conrad’s son, who went by the name “Finis” had owned a hotel near the River Church, St. John’s Lutheran, a plastered over log building built in 1815 where they were all members. Since 1842, Finis now owned a hotel across the county line in Allenwood.

With owning a hotel and the good reputation that Conrad and Finis had in the area, there was always farrier work to be done. Also, the farms in this area were well-tended by their owners and there was metal to be repaired on machinery and horse tack. Charles and his wife Elizabeth needed a steady income to raise their eight children. Their eldest, Artemus, at fifteen years of age was already a strapping young man who was learning the blacksmith trade. Furthermore, he and second son, Henry, could be hired out to help Charles’ brother, Conrad; his nephew, Finis, at the hotel; or even a neighboring farmer if more income was needed.

The house that already stood on their new land was small for ten people but Charles would soon remedy that by building on an addition. He was not only an accomplished blacksmith, but also a carpenter and saddler. He had learned most of his skills from his father, John. Charles’ mother had died 15 years earlier when he was only fourteen.

His father, John, had grieved all those years after his wife’s death. He had often taken Charles aside and told him wonderful stories of his father, Andreas, the grandfather whom Charles never knew. John would sit by the fire in the evenings with young Charles and describe his previous life in Berks County, his adventures in Philadelphia as an apprenticed tailor, what it was like to be a soldier during the great war for independence, and of his days courting the young Magdalene Dreisbach. In return, Charles looked to his father and the grandfather as giants of their times.

His father John would also talk about when he moved to the Hidlay Church area in 1806 to be near his nephews, Henry and Andrew. These two sons of his brother, Michael, had already established successful homesteads in that area. When John moved there, he purchased 500 acres to settle on with his wife and six sons (Charles and his brother, Jonas, were not yet born), the future looked rosy. And it turned out to be very much indeed! John had been a pillar of the community and of the Lutheran church at Hidlay. But John also had a checkered past which he had no problem relating to his sons, especially Charles.

Charles remembered distinctly the night a few months before his father’s death when John told the story of “the book,” as it was called. The old German tome was kept in a wooden box and was taken out by John on occasions when, as he said, “I need to understand how father Andreas would have solved this problem.”

Andreas had been a Lutheran Pietist and had considered Johann Arndt’s book Wahres Christentum almost as important as the Holy Bible. Andreas had willed it to John, due to John’s wayward life up until the day of Andreas’ death when the book came into his possession. From that day forward, John’s life was changed and although he did not consider himself a Pietist, he strictly followed the precepts of German Lutheranism and the example of Andreas’ life.

That evening, a few months before John’s death, Charles was given Wahres Christentum by his father as he said, “Charles, this holy book came from Wurttemberg with my father in 1737. He lived his life through its words. He taught me from its pages. Now, it is yours to search for God’s answers to your problems and to keep you on the straight path.”

However during the past year, Charles had not opened the book once. It was not because he did not respect its message nor the tradition it held in his family. It was because, although he could speak some Pennsylvania Dutch, he could not read the Hoch Deutsch that the book was written in. He was not sure what to do with the book.

Charles’ children knew that there was a book in the wooden box which their father and mother kept under their bed, but they were never told what it was. And so it was never spoken of. A few years went past and in 1850 sons Artemus and Henry were confirmed at the River Church by Rev. Boyer. This got Charles to thinking one Sunday in 1851.

Charles took out the book and carried it to church. Communion was being held that Sunday. He placed the worn book beside him on the pew and before the service began, he prayed and wondered where the book really belonged: under the bed to catch the dust, in the hands of one of his sons, or in God’s house? Charles looked across the aisle at his wife Elizabeth, his daughters, and his nieces. Beside him sat his sons and his brother, Conrad. Charles thought back to his father and grandfather and the importance of a book that was not being used. After church, Charles waited and was last to leave the church.

As he shook Rev. Boyer’s hand and declared, “Good Sabbath,” Charles asked to speak to the pastor privately. They went into the sanctuary and sat in the back pew.

“Pastor,” Charles began, “I have a book that was passed down from my grandfather Andreas to his son John, who was my father. I am now in possession of it. It was a pillar of faith for my father and grandfather. But, I have problems reading it as it is in formal German and script. I wrote its history on a piece of paper which I have placed inside the cover. I wonder if you would mind keeping it here in the church for a time, as I am not sure which of my sons to pass it to. With my blacksmith shop so close, I often fear a house fire may occur. And, perhaps this book has a more important place in the church rather than sitting in an old box.”

Mark Hagenbuch standing by the gravestone of Charles Hagenbuch in the Delaware Run, St. John’s Lutheran Church cemetery

Rev. Boyer took the large tome from Charles’ hand and immediately recognized it as the Pietist work of Johann Arndt. When he was a student at Gettysburg Seminary, one of the religion professors had warned them against the scurrilous writings of Arndt. The Pietist movement was looked upon by the Lutheran clergy as full of wrongful teachings. The students had been shown a translated copy of Wahren Christentum only to be told to disregard it as medieval tripe!

The pastor took the book from Charles’ hand and said, “I will place it in a safe place. When you want it returned, just ask.”

Later that day, Rev. Boyer placed the worn book on a back shelf behind other books that the Lutheran church did not acknowledge as worthwhile for study. He was not deceitful; he would not destroy the book. He hoped that it would stay hidden behind the other censored books on that shelf and not be discovered to lead any of his congregation astray.

For the next year or so, Rev. Boyer considered what was to be done about the book. He traveled to other churches in his pastorate, one of which was the Lutheran church in the nearby village of Washingtonville. There were cousins of Charles and Conrad who attended the Oak Grove Lutheran church which was located near to Washingtonville. So, he often had the name Hagenbuch ringing in his ears, but his memory of the book that Charles had given him slowly faded. Eight years later, Rev. Boyer left the area to take another charge and did not return to St. John’s, the River Church.

During all those years after Rev. Boyer left St. John’s and the Rev. Albert became pastor, the Hagenbuch family was faithful in attendance. Charles still thought the book to be in safe keeping at the church, no different than his grandfather Andreas and his father John had kept the book safe in their own homes. In fact, knowing it was in the church with the other books of importance (or so he thought) gave him peace of mind.

In 1867 Rev. Albert left St. John’s River Church for another charge and a young seminarian, Rev. Billheimer, took charge of services. It was during this time that the church grew out from the seams and a new brick sanctuary was built. In 1868 the congregation welcomed a new minister, Rev. Keller.

Rev. Keller knew nothing about a pietist book housed in his church. When and how the book vanished from sight during those years is not known. Moving furniture and books out of the old church and storing them until the new church was built certainly created an upheaval. Arndt’s Wahren Christentum was still considered as promoting beliefs that did not follow the doctrine of the Lutheran Church in America.

In 1870 Charles Hagenbuch died. Due to dementia or sickness or not enough time to tell his story of the book before he died, the existence of the book was never discussed nor asked about by any of the Hagenbuch family. One hundred years passed.

One day in 1969, a few months after Rev. Roy Gutshall took over the charge of St. John’s Lutheran, now called Delaware Run instead of the River Church, he was looking through some old German bibles that were part of the church’s collection. Tucked in among them was a large, leather bound tome that he recognized was not a bible.

Carefully opening it, he saw that it was a copy of Johann Arndt’s book, which supported the precepts of Lutheran Pietism. Rev. Gutshall was familiar with the book, Wahren Christentum, and had handled copies of it in the library at Gettysburg Seminary. However, discovering the date when it was published in Germany, he knew he had never handled such an ancient copy.

Inside was a hand written note from a Charles Hagenbuch dated 1851, relating that the book had been owned by his family before 1737 when Charles’ grandfather Andreas had immigrated to America. It had then been passed on to Andreas’ youngest son, John, who was Charles’ father. Charles had written that he was giving the book to the church for safe keeping, and it was to be passed on to the descendants of Andreas Hagenbuch.

Rev. Gutshall was familiar with several Hagenbuch families in Columbia County, Pennsylvania who had been members of his first pastorate at Hidlay church near Bloomsburg. He had lost contact with those congregants over the years; and although only being at St. John’s for a few months, he knew there were Hagenbuchs in the areas of Milton and Washingtonville.

This book was certainly a family treasure that needed to be given back to the family. As he closed the book reverently, he decided to look in the telephone book and call one of the families about the book. Out loud he spoke to himself, “I wonder what secrets this book holds. I wonder what its story is. I doubt if we will ever know.”

May God enlighten us all by the Holy Spirit, so that we may be pure and without offense, in faith and in life, ’til the day of our Lord Jesus Christ (which is near at hand) with the fruits of righteousness, to the homage and praise of God. Amen.

–Wahren Christentum by Johann Arndt, 1606

This ends the story of “the book.” Although containing some facts, Part 4 is the most fictional of the four parts. The last few paragraphs which occur in 1969 are all fiction. However, Rev. Roy Gutshall certainly became acquainted with the Hagenbuch family since he performed the marriage ceremony for his daughter, Linda Faye, to Mark Hagenbuch; and he baptized their three children, his grandchildren: Andrew Hagenbuch, Katie (Hagenbuch) Emig, and Julie Hagenbuch.

Part 5 will draw conclusions and list the facts contained in the story of “the book.”