The Book, Part 2

Below is the continuation of a short story in the historical fiction genre regarding the book Wahres Christentum (True Christianity), which Andreas Hagenbuch (b. 1715) willed to his youngest son, John (b. 1763).

The Book, Part 2

On a Saturday in 1782 after an hour of musket drill with the Northampton Militia and after several hours spent in the local tavern, John Hagenbuch returned to his brother Christian’s house to see a letter on the Kichtisch (kitchen table) that was addressed to him. He recognized the handwriting of the address as his father Andreas’s. He sliced some bread and with it ate a heel of cheese. He ignored the chatter of his brother’s children and did not even look up when his sister-in-law, Susanna, spoke to him.

John took the letter into the next room, broke the seal and read what he reacted to with a groan. His father was demanding that he return to the homestead in Berks County, but no explanation for this was given. Within a few days, John arrived by horseback at the house and farm where he had lived as a child. After putting his horse in the stable, he entered the house where his mother greeted him. She had already laid out some food on the table. A few of his nieces hovered around him, his sister Barbara, and his sister-in-law, Eva Elizabeth, both acknowledged him but then disappeared. And, in the corner, the Stub, sat his father.

John stood and confronted his father shouting, “You cannot do this to me, Father. I refuse to serve another man, especially a tailor!”

At that, Andreas stood and faced his son. With an almost monotone voice, he told John that he would either comply with this demand or he could leave and not come back. And, if he did that, he would not be treated as a son ever again. John was a young man who knew which side his bread was buttered on. He knew that meant he would inherit nothing from his father when Andreas died. Although often a “bad egg,” John truly loved his father and also knew when his father was determined in a decision.

John slowly sat, Andreas looking down on him. This time, speaking in the local language, John asked Andreas to give him one more chance. He was truly sorry for his years of disobedience. He did not beg, and he was sincere.

Andreas sat down beside him and put his arm around him. How many times must he forgive his most beloved son, John. He reached up and took down the Heilige Schrift from the shelf and turned to the 18th chapter of Matthew. He read the words of Christ to himself; the words concerning forgiveness.

Then Andreas reached for Wahres Christentum, Johann Arndt’s book on true Christianity. Turning to a well worn page, he read aloud a passage to John which Andreas had read over and over this past year:

Repentance, repentance is the true confession. If you have it in your heart, namely, true regret and faith, Christ’s blood and death will absolve you from all your sins.

Putting his arm around John and brushing the hair away from his face, Andreas whispered, “You shall have one more chance and you will do as I tell you. Otherwise you will be off to Philadelphia to learn the tailoring trade. Here is what you must do.”

The next day, John was riding back to his brother’s house in Northampton County. Upon leaving the Berks County homestead that morning, all of his family had wished him “Gluck,” even brother Michael. His parents had walked with him down the road until they reached the Rosenthal Kirche. There they parted with John’s assurance that the five acres that Andreas had agreed to sell him—which lay next to brother Christian—would be used to build a house and start a business.

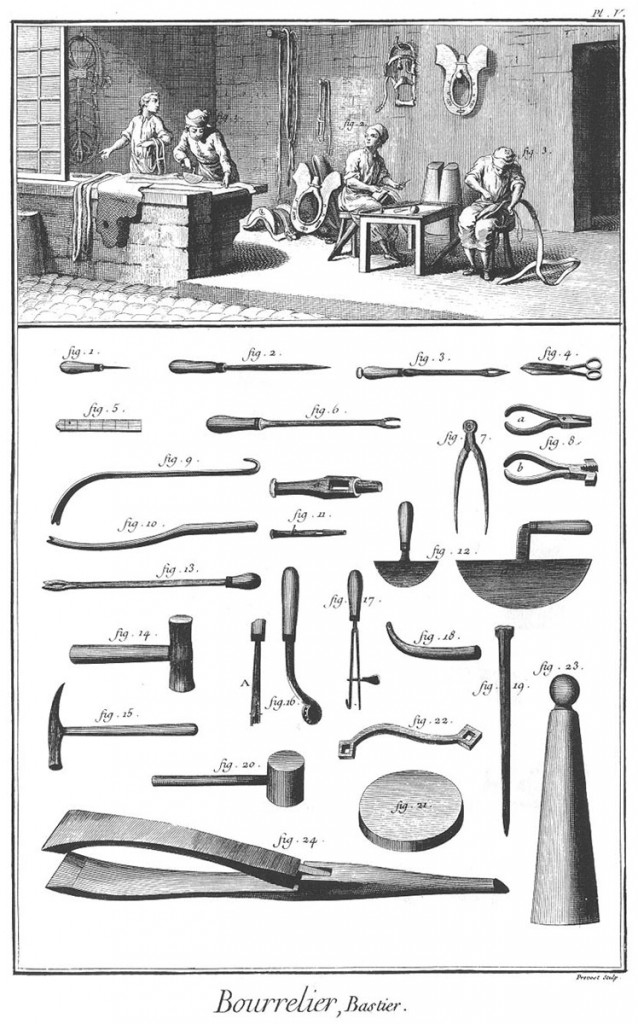

Harness and saddle maker workshop and tools. Diderot, 1763. Credit: The Encyclopedia of Diderot & d’Alembert Collaborative Translation Project

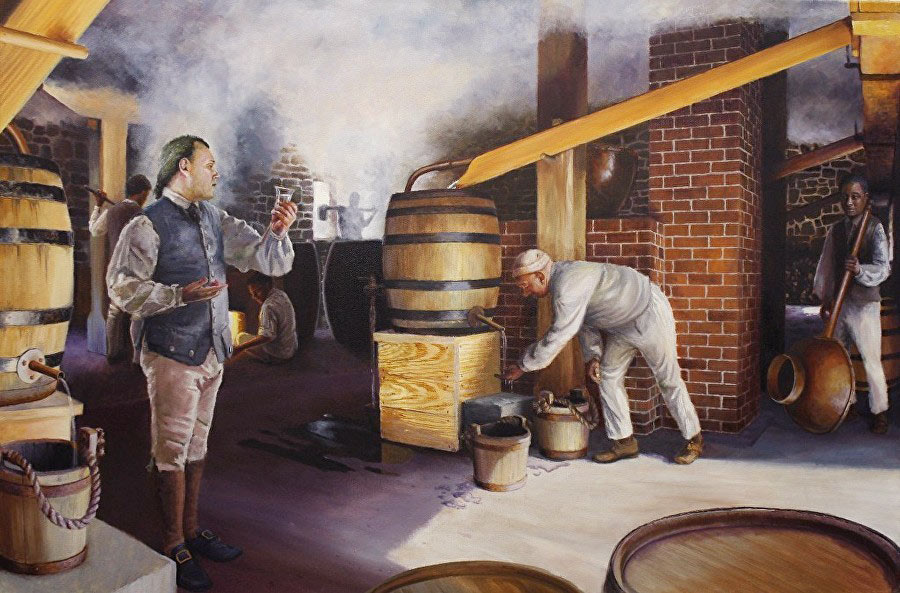

The financial arrangements were such that there would be time for John to build a successful saddlery business so as to net him enough profit to pay the note on the land which Andreas held; and possibly have enough money to construct a small house. While the amount of money was being amassed, John would live with Christian, work at his distillery and also do the leather work to start his own saddlery.

For John, this would be a new life and possibly, finally, at the age of 19 he was maturing into a responsible young man. Perhaps, it was the alluring smile of the Dreisbach girl that was making the difference. Whichever it was, 1783 was looking to be a good year for him.

The year went by quickly and John did work hard. He spent most of the daylight hours working with his brother Christian (who paid him as he would any hired man) and making saddles, harnesses, fly nets, anything made of leather.

John even worked at his brother’s forge to fashion the buckles needed for the leather tack. He made the payments requested of his father on time and he even found time to informally court his sister-in-law’s cousin, Magdalene Dreisbach. However, she being only 17 going on 18 years of age, marriage was still out of the question.

The good behavior lasted into the next year. But, the winter was difficult for John. His saddlery business went sour and although he asked his brother Christian for an advance on his wages so he could continue to pay on the note for the land, his ready cash dwindled. Of course, he was still John Hagenbuch!

It is unusual for any man to do a complete turn around until he hits rock bottom. With little cash and two months behind in the payment on his land to Andreas, John began to frequent the local tavern in the evenings. He failed to pay his respects in a timely manner to Magdalene Dreisbach as he once did. And, when she finally told him one evening, after he had been to the Tavern for several hours, that he might not be the man for her, he flew into a rage.

John was at his worst as he left Magdalene in tears after a rough retort to her, and at his very worst when he arrived home at brother Christian’s to bad mouth everyone in sight. Christian had had enough of his brother that evening and told him to pack his belongings and head back to Berks County. In disgrace, John left the next morning, looking back at his piece of land which had no house, no business, and no Magdalene.

Unbeknownst to John, Christian had sent a message by post rider to his father Andreas before John had left that morning. When John arrived at the homestead and entered the house, the atmosphere was different than the last time he had been there. No one was there to greet him and the house was completely quiet.

John stood inside the doorway, his head down, completely defeated. Finally, father Andreas walked out from the bedroom and stood looking at his John. However, this time, John spoke first.

“I have not fulfilled your wishes for me, Father,” he began. “I did try, but I back slided. I am ready to go to Philadelphia as an apprentice, if that is what you still want.”

After a moment of quiet, Andreas replied, “Ja, it is what I want. You will leave tomorrow morning with a letter for the tailor, Herr Hertzog. Now, come sit with me in the Stub while I read.”

He opened the book, Wahres Christentum, to Chapter 7:

When God, the Lord, created man according to his image in perfect righteousness and holiness and adorned and beautified him with great divine virtues and gifts, brought him forth as a perfect, beautiful masterpiece, as a high, noble work and piece of art, he planted three chief properties in the human conscience so deeply that they were never able to be rooted out, indeed, not even in eternity. First, he gave a natural testimony that there is a God, second, that there is a final judgment (Romans 2:15) and third, the law of nature or natural righteousness by which honor and shame might be distinguished and joy and sorrow might be discovered. There has never been a people so evil and barbaric that has denoted that there is a God, for nature has witnessed this to them internally and externally.

Indeed, they have discovered in their consciences that there is not only a God but that he is also a righteous God who punishes evil and rewards good, since in their consciences they found fear or joy. From this they deduced further that the soul must be immortal as Plato clearly insisted. Finally, from the law of nature, that is, from their inherited natural love, they saw clearly that God is the source of all good in nature. Further, they understood that this God must be served with virtue and a pure heart. Therefore, they placed the highest good in virtue and out of this the schools of virtue of Socrates and other wise philosophers arose.

Special thanks to White Historic Art for use of the paintings included in this article.