The Book, Part 1

I expect most people don’t regularly read what I term as pure history. However, many people read historical fiction where the plot, the setting, and the characters are located in the past; but the story has pieces added that cannot be proven or have no truth attached to them. Historical fiction is fun to read and is very popular. Books like A Tale of Two Cities and War and Peace have stood the test of time.

Andrew and I sometimes discuss the “what ifs,” “do you thinks,” and “maybes” of our family history—the curiosities and mysteries. One of these that gnaws on my brain is: Where did the book, Wahres Christentum (True Christianity) finally rest after Andreas Hagenbuch (b. 1711, d. 1785) willed it to his youngest son, John Hagenbuch (b. 1763, d. 1846)? Several articles about “the book” and about “Runaway John” have already been written. For the past few years, I have wondered if this religious book had any bearing on John’s seeming change from a possible ne’er-do-well to a model citizen, marrying favorably, and raising eight successful sons.

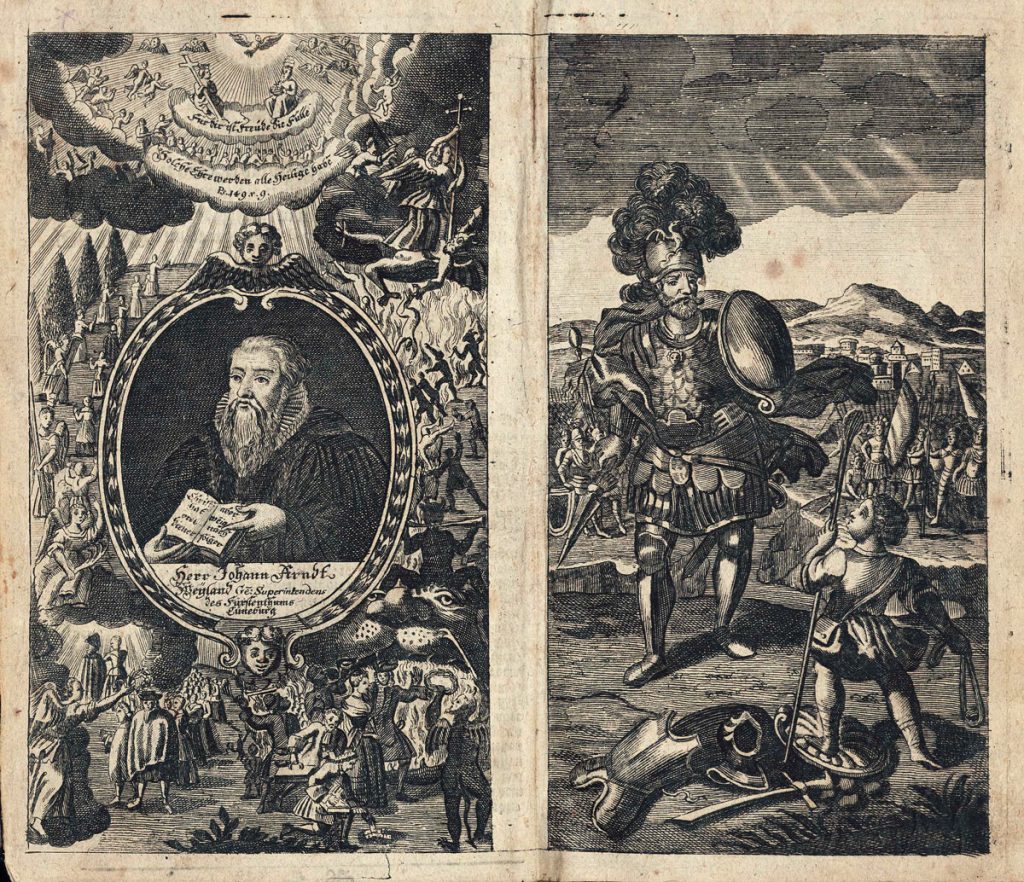

So, the following is a short story of historical fiction of what might have happened, or what could have happened to “the book,” and the possible influence it had on the lives it touched. Keep in mind, that it is not known if the book came to America with Andreas Hagenbuch in 1737, if Andreas purchased it once he arrived, if the book was regularly read by his son John when he gained possession of it, or if the book was passed on from John to any of his sons. We only know that this book concerning Lutheran Pietism was written by Johann Arndt in 1608 and was to be given to the youngest son, John, upon Andreas’ death in 1785.

The Book, Part 1

Wahres Christentum was a large volume, leather bound, that in 1737 traveled safely from the Kingdom of Wurttemberg in Germany with its owner Andreas Hagenbuch. The book was a prized possession, having been passed down from his father Hans Michael and according to what Hans told Andreas upon his death in 1735, it had been in the family since the days of the family living in Switzerland. Andreas had thoroughly read the deeply pious words of the book several times before leaving for the long trip to America; and the only other things dearer to him than the book were his new wife, his two children by his first wife, and of course God’s love, Christ’s suffering, and the Holy Spirit. So, in the weeks’ long journey across the Atlantic, Andreas Hagenbuch was surrounded by the three people and the religious precepts that were the loves of his life.

Before leaving his small piece of land and business, which was located near Heilbronn, Andreas had built a sturdy box with hefty clasps for the book to rest inside. So, the book was kept safe during the voyage and the travel from Philadelphia to his newly acquired land in Berks County, Pennsylvania. During the years that Andreas lived, farmed, and dabbled in various business ventures, the book became his religious stead. He read and reread the words of Johann Arndt and so many of the passages became part of his inner being:

Faith is a deep assent and unhesitating trust in God’s grace promised in Christ and in the forgiveness of sins and eternal life. It is ignited by the Word of God and the Holy Spirit. Through this faith we receive forgiveness of sins, in no other way than through pure grace without any of our own merit (Eph. 2:8) but only by the merits of Christ. For this reason, our faith has a certain ground and is not unsteady.

Andreas was certainly a Pietist and rarely attended at the Rosenthal, New Bethel church, which was located less than two miles from his home. Instead, he spent the Sabbath in his own home, surrounded by his family and sometimes his neighbors, reading and lay preaching from the Holy Bible and Wahres Christentum. Andreas needed the strong individual faith which the book promoted because, though his life was free of poverty and though he had the respect of not only his neighbors but also others who looked to him as the “go to” man for advice and financial aid, Andreas experienced heartache.

Of course, most people living during those times of the French and Indian War, and the Revolutionary War witnessed death and destruction. Andreas was no different. Not only were there horrible raids from Americans Indians and the possibility of raids and war from British soldiers, but Andreas also lost his second wife to a malingering illness after the birth of their son Christian. The marriage of Andreas to his third wife and continued success in his businesses certainly assuaged the sadness from those previous incidents. However, there was a problem which he never seemed to be able to solve: his youngest son John’s sinfulness.

John was Andreas’ most beloved son. Born when Andreas was in his years of fifty and to his third wife, he was a beautiful child, slight of build, with delicate facial features. Andreas and wife Maria Margaretha doted on him as the only male child of that union. In today’s vernacular, one would say that John was spoiled and the other children recognized this. When the youngest ones came down with a slight case of smallpox, John seemed to be given a bit more care, and Andreas could be seen praying fervently over him and consulting the book regularly. Although Arndt’s words about suffering were strongly believed by Andreas, it was difficult now to accept them as he watched his young son suffer with smallpox.

In suffering God comes to us, we deserve far greater punishment, God does not mistreat us, God has patience with us, Christ made suffering a sanctifying thing, and eternal glory follows upon suffering.

John, along with the young ones, lived through the small pox infection, although John’s once beautiful face was now marked. Maybe, because of the once beautiful face now pocked, or maybe because he had been spoiled by his parents, or maybe there was an innate flaw in John’s character, the young boy became somewhat defiant and “uppity” with his siblings. As John grew older, Andreas continued to be outwardly satisfied with John’s maturity into a young man. But Andreas knew his Bible well enough to see the similarities between the boy and Absalom of the Bible, King David’s youngest and most loved son. John was a wild, free spirit.

Even though his three older brothers had “joined up” to fight the British in the Revolution of 1776, John had been forbidden by his father, Andreas, to march off with the Pennsylvania armies to fight the British. But against his father’s wishes, John ran off in 1779—he being only 16 years old—to march with the soldiers heading north to fight with General Sullivan against the Indian allies of the British. He had even given a false name when the soldiers’ roll was taken so that the other men in ranks could not identify him!

It was a long and tiring expedition with fierce fighting, and when he returned home, just like the prodigal son, John was welcomed with open arms by Andreas. This was not the same welcome given by Michael, Andreas’ second son and half brother to John, who like the brother of the Prodigal in the Bible, detested John for not obeying their father while he was working on the farm in service to their father!

That evening, after a fine meal had been enjoyed by the whole family in celebration of John’s safe return, Andreas took down the two prized books from the shelf: the Heilige Schrift (Holy Bible) and Wahres Christentum. Much to Michael’s humiliation, Andreas not only read the parable of the Prodigal from Luke 15, but he also quoted from the book, likening love of a neighbor to love of a brother:

If one knows and feels the power of God truly in his heart, humility follows, so that he humbles himself before the mighty hand of God. If he knows and senses God’s mercy properly, love for neighbor follows. No one can be merciful who has not understood God’s mercy.

Glancing at John while father Andreas taught from the book, Michael thought he caught a smirk on his brother’s face.

John continued to lead a life that was very different from his family. He spoke out against his father Andreas quite often, showed his disgust for the life in northern Berks County, became lazy, and would often disappear for several days. But to the chagrin of the whole Hagenbuch household, patriarch Andreas always seemed to forgive him. One day in 1782 it came to a head.

Even though the war with Great Britain had ended in 1781, a treaty had not been signed and British soldiers were still in occupation of some areas of the newly formed United States. Local militias were still active and welcomed recruits. John had been living at times with his brother Christian over in Northampton County. Christian and his family seemed to have a positive effect on John; and maybe that was because he would sometimes have contact with one of the Dreisbach “Frauleins”, Maria Magadalene, who was a cousin to Christian’s wife, Susanna! But, even a possible sweetheart did not keep John from wanting more adventure. For sometime in 1782, he joined the Northampton Militia in hopes of, as he saw it, a fancy uniform and spending time with his comrades in arms.

This latest infraction against Andreas’ hopes for John was the final straw. His plans for John’s future, be it business man, farmer, tanner, saddler, distiller, anything that was a solid vocation and reputable, was dashed with the news that John had “joined up” again. Without consulting John, Andreas sent a message to a friend of his in Philadelphia, Andrew Hertzog, a well-known tailor who was looking for a servant to whom to teach his trade. John was not yet of age when he could legally make his own decisions and this last decision to join the militia, could be annulled by Andreas with no trouble.

Once again, Andreas turned to the book, Wahres Christentum for an answer based on Johann Arndt’s words.

No one can love God unless he hates himself, he must set aside his own will and mortify it. The more a man loves God, the more he hates his evil will and affectations, the more he crucifies his flesh with its lusts and desires.

The answer was clear to Andreas. John must now be given up as a servant to another so as not to dwell on his own desires. As a final act for this decision, Andreas took his Bible, the Heilige Schrift, from it’s place on his shelf and turned to the 18th chapter of the second book of Samuel. Determined, yet grieving for his beloved, sinful son, he read verse 33 aloud, “O my son Absalom, my son, my son….” , then closed the Holy Book and prepared the letter to be sent to John.