Tell Them the Story

As a warning to our readers, this article describes a suicide in the early 20th century.

While writing my last article about November dates, I was looking through the photo archives for images of the people I wrote about. I came across some photos that were interesting and decided my next article would be about photos and the stories behind them. That evening as I was reading through my Bible devotions, I came across scripture that spoke to me concerning the planned article.

Joshua, the fourth chapter:

So Joshua called together the twelve men he had appointed from the Israelites, one from each tribe, and said to them, “Go over before the ark of the Lord your God into the middle of the Jordan. Each of you is to take up a stone on his shoulder, according to the number of the tribes of the Israelites, to serve as a sign among you. In the future, when your children ask you, ‘What do these stones mean?’ tell them that the flow of the Jordan was cut off before the ark of the covenant. When it crossed the Jordan, the waters of the Jordan were cut off. These stones are to be a memorial to the people of Israel forever.”

It struck me. Joshua wanted the story of the 12 tribes told to Israel for generations. An important story then; and an important story now! That’s what Andrew and I do—we tell the story of our family. We do it with details and with photos and with interest, so our readers learn about the family and most times in an entertaining way. I went to bed thinking about this and woke up a few hours later, which is not unusual. I lay there for over an hour thinking all this over, and the question kept running through my mind: How much of the story do we tell? Do we tell those stories that may disrepute someone? Do we tell stories that are family tales and may not be completely truthful? Do we tell stories that may cause problems between living family members?

I believe Andrew and I are “gentlemen of discretion.” We do know stories about our family that could cause problems. We find stories about our people when we dig through documents online such as censuses and newspaper articles, as well as when we sift through the paper archives we maintain. Also, there are the stories that are told to us. Over the past nine years we have written down some of these stories. One of the earliest that I wrote about was One Silver Dollar.

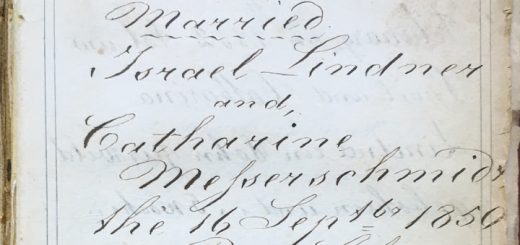

Is this story completely true? Great Uncle Perce told it to me first. Maybe he got a few things wrong as he was in his 80s at the time. I was probably about 10 years old when he told it as we stood in the Oak Grove Church cemetery gazing on Uncle Gene’s stone. Did my young imagination add some details to the story? Of course, we have never looked at my great grandmother’s will to check out the silver dollar details. However, the story was supported by my father’s first cousin, Bruice Hagenbuch in 1972 when I mentioned it to him. Over the years, the story has influenced Great Grandmother Mary Ann (Lindner) Hagenbuch’s personality so that we think of her as a no-nonsense mother!

While working on this site, Andrew and I have discussed the task of sharing stories about relatives. We are certainly discreet and have weighed in on the question: Is the story’s information useful in a harmless way or will it negatively color the way we think of someone who is no longer with us and cannot confirm or deny certain details? In past articles, we have mentioned a few times when there is a birth out of wedlock. But, we make sure it will not disrepute anyone living. We have written about some family members that have broken the law, but these are in the past and do not hurt present-day family members.

The question continues in the back of my mind: Should stories that are harmful to the reputations of our ancestors be suppressed and forgotten? Andrew and I don’t believe in airing our dirty laundry to the world. This is where discretion and judgement come into play. If we believe that an unhappy story should not be shared then we must be careful not to write it down. At this time the few stories Andrew and I have chosen not to share are in oral form. We may choose to share the story orally with someone who might benefit from it and keep it to themselves. Those stories that we decide are too sensitive to share may never be passed on through our family history. That’s the choice we make as discretionary family historians.

I realize that some of you who are reading this might have a skeleton in the closet that is known or unknown by others. Be reassured that if any information has been told to Andrew or me in confidence, it will not be shared. Be reassured that if we know of family details that are personal and could hurt someone, they will not be written about. In the past few years, there have been some stories shared that are no longer harmful as the people involved have passed away or the details are no longer embarrassing because many years have passed.

Take, for instance, this story about myself. At one time I would not have shared it as it humiliated me. In 1964, my parents took my brother, Dave, and me to Williamsburg. My Mom, Irene (Faus) Hagenbuch (b. 1920) thought it would make a funny photo if I was put into the stocks. My feet were clamped in but the seat, which was covered in strap iron and very hot from the sun, was beyond my short stature. As my ankles were fastened, I had to reach back so I wouldn’t fall short of the “hot seat”. My hands were burned from the metal! At that moment, with me screaming and crying, Mom snapped the photo. Although an innocuous story to most, the incident made me angry for years, especially when my mother would show the photo to others.

On the more serious side are stories like the one of my great grandfather, Samuel Hilner. While not a Hagenbuch, his story is representative of the dangers of depression driven by economic hardship. It’s a story that my mother never told until later in life. During the Great Depression she went to live with her grandparents, Samuel and Louisa (Miller) Hilner. Samuel was a farmer, but the toll of those years trying to make ends meet came to a bitter end in 1932 when Mom was 12 years old.

As she told the story: She and her grandmother were baking bread one morning and when Grandma Hilner reached into the flour bin, she found a note that read, “Louisa, I’m sorry.” Grandma Hilner ran out to the barn screaming “Oh Sam! No!” But, it was too late, Samuel Hilner had hung himself from a barn beam. Mom was always emotional when she told this story. She was a young girl and, unfortunately, was a firsthand witness to a family tragedy. It’s a story that should now be told but with sincere empathy.

Suicide affects a family deeply. Its scars can last for years and years. We have to decide if these sensitive family happenings are worth dredging up hurtful memories. My father had a painful memory which he only shared with me during the last few years of his life. My mother passed away in 2011, and I believe it was soon after that Dad told me this story about his brother Lawrence who was born in 1921 and died in 1922. We were driving around the area of Montour County, Pennsylvania where our family had lived. We may have even just visited Oak Grove Church cemetery where Lawrence is buried, when Dad told this sad story.

He started by saying that no one ever seemed to know why Lawrence died. Although he may have been born with health issues (as surmised by his early baptism), Dad poignantly continued with the following:

Mom [Hannah (Sechler) Hagenbuch] was hanging out wash, and I was watching Lawrence crawling around on the ground. Once in a while he would pick up chicken dirt [feces] and put it in his mouth. I never told Mom about it. I wonder if that’s why he died? I should have told Mom about it.”

Dad told this story to me several times before he died in October of 2012. I could tell he felt guilty for not telling my grandmother about what Lawrence had done. Each time I would tell him that we’ll never know. He was only a boy of six years old.

Unlike the story from the book of Joshua, some stories are not worth sharing if they cause present or future concerns. Family historians should make decisions as to what can be told now, since telling it in the past may have created family squabbles, tainted someone’s reputation, or caused undue embarrassment. As the Greek writer of tragic plays, Aeschylus, stated: “You should learn, though late, the lesson of how to be discreet.”

Telling stories of family histories can be messy, as we are all humans and make mistakes. But, the decision to tell about those mistakes requires judgement and then discretion as to whether the story is worth telling especially for posterity. Andrew and I make those decisions responsibly and expertly. As God told Joshua: “Tell them the story”. We must make sure that the past is not forgotten, that our family stories of value become present knowledge, and that future generations are guaranteed knowledge about our family.

Joshua, the fourth chapter continues:

And those twelve stones, which they took out of Jordan, did Joshua pitch in Gilgal. And he spake unto the children of Israel, saying, When your children shall ask their fathers in time to come, saying, What mean these stones? Then ye shall let your children know, saying, Israel came over this Jordan on dry land. For the Lord your God dried up the waters of Jordan from before you, until ye were passed over, as the Lord your God did to the Red Sea, which he dried up from before us, until we were gone over: That all the people of the earth might know the hand of the Lord, that it is mighty: that ye might fear the Lord your God for ever.

Tell them the story—discreetly, responsibly, and for a reason. The most important part of family history is names, dates, and places as this is the foundation where it all begins. But family stories bring our people to life, make them real, and help us to learn from their past lives.