Stuck on Charles W. Hagenbaugh, Part 4

In 2021, I discovered Charles W. Hagenbaugh living in Montana with his wife, Albertina (Tepper). I had no idea who he was or where to place him on our Hagenbuch family tree. I set his information aside in hopes of figuring it out someday. Earlier this year, I resumed my investigation of Charles’ life and began to share my findings through a series of articles.

In Part 1, we traced Charles’ life backwards from his final resting place in the San Francisco National Cemetery to his work at Fort Assinniboine in Montana to his origins somewhere in Ohio. In Part 2, we explored Charles’ years living in St. Paul, Minnesota and attempted to connect him to the Hagenbaughs he shared a home with there. Finally, in Part 3 we examined his death certificate for additional clues about his life. While this yielded few new details, it did aid in unearthing one more document—Charles’ probate file in Silver Bow County, MT.

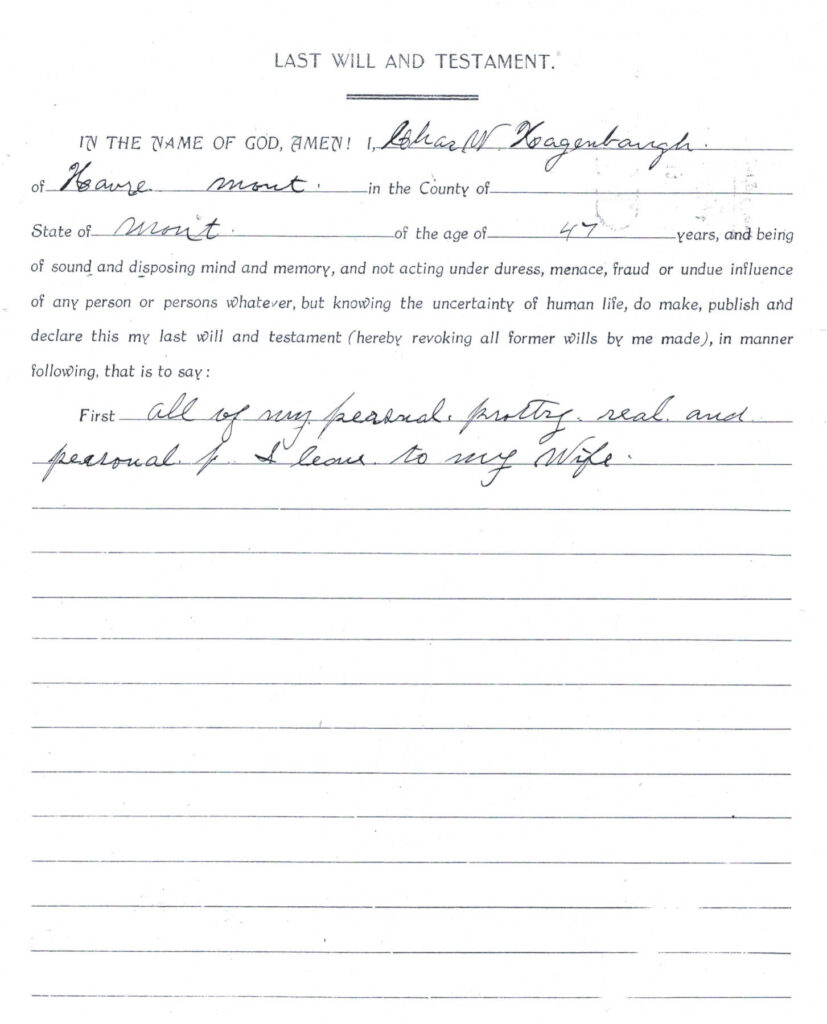

To gain access to these records, I contacted the Butte-Silver Bow County Archives in April. After a quick search, they determined the files were not there and still with the District Court. I contacted the Clerk of the Court and requested copies of Charles Hagenbaugh’s probate documents, including his will. I hoped these might mention the name of a relative and draw a clearer line from Charles to his parents.

A month later, I received a package of legal-sized photocopies from the Clerk of the District Court for Silver Bow County, MT. Inside I found Charles’ will, letters of administration for his estate, and papers relating to the sale of a home. I began leafing through them to see what I could uncover.

The first thing I noticed was Charles’ age when he wrote his will—47 years old. Since he signed the document on January 18, 1909 and was supposedly born on February 27th, it would seem he was born in 1861. However, this year conflicts with the two other birth years that have been found for him: 1862 and 1863. Which year was it?

Charles undoubtedly saw his will before he signed it, suggesting that the information should be correct. Perhaps, noting that it was 1909 and he would be 47 in a few weeks, he erroneously recorded 47 as his age when he was presently 46. If true, this would mean he was born on February 27, 1862—a date also supported, in part, by his death certificate.

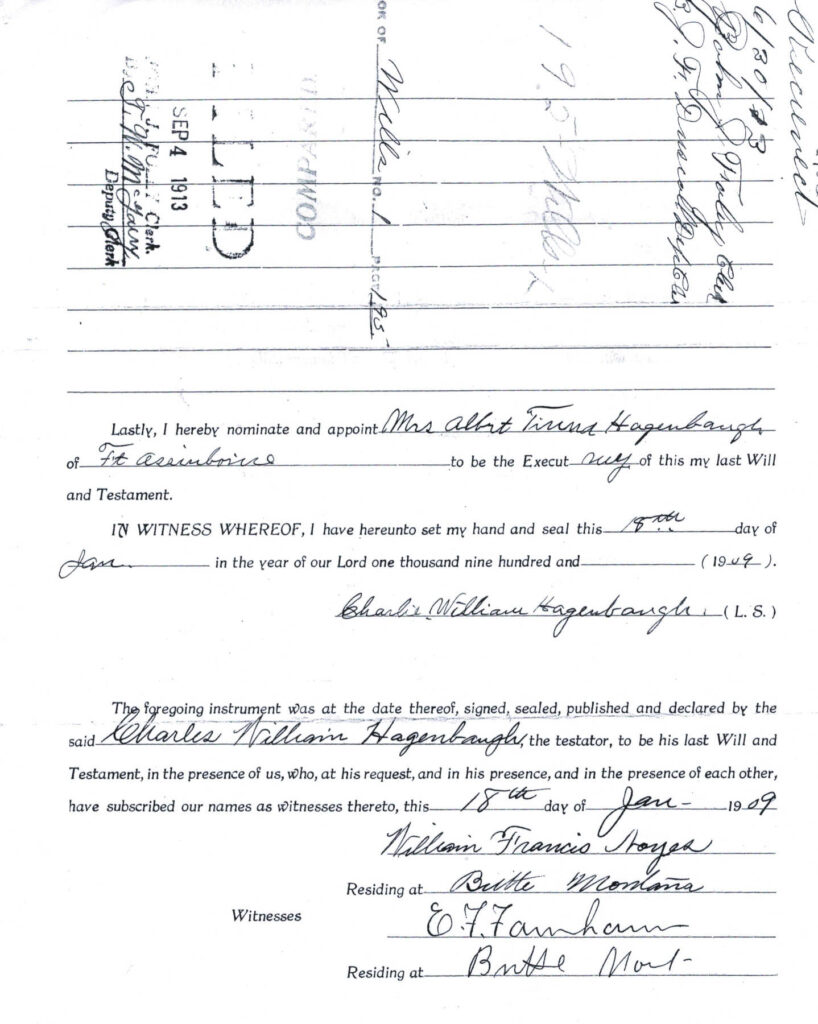

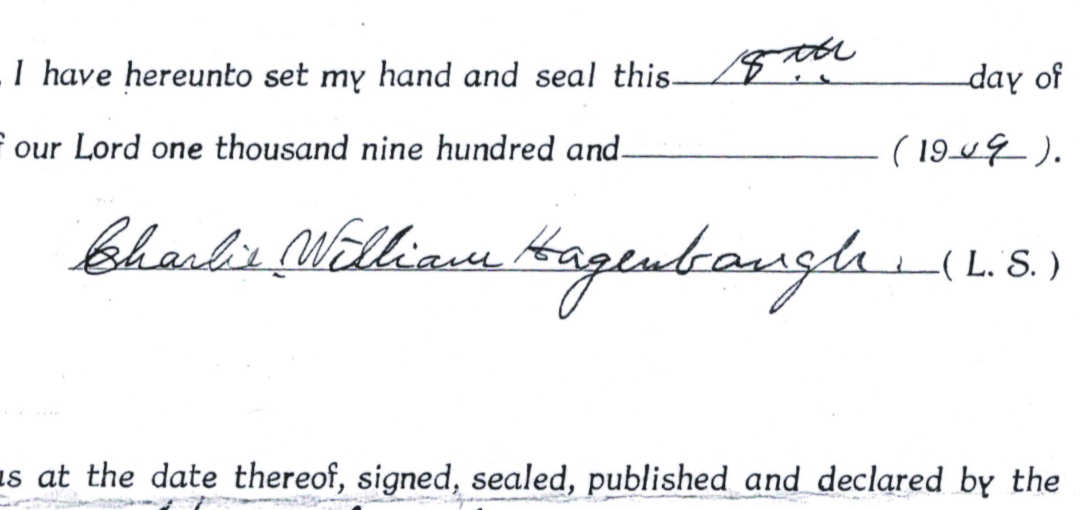

Another interesting detail found on the will comes from Charles’ signature. Although his name is written as “Charles” elsewhere in the document, he signed his name “Charlie.” While hardly an earth-shattering piece of information, knowing that he went by the nickname Charlie adds another layer to his life story and personality.

As discussed earlier, I had hoped the papers inside the probate file might finally prove without a doubt where Charles should be placed on our family tree. Unfortunately, the only relative named in the documents was his wife, Albertina. The will makes it clear that she is the exclusive heir to all of his property and the executrix of the will. Curiously, she declined this role. A notarized letter shows that she appointed Gustave A. Meyers to administer her late husband’s estate. This may have been because Albertina was living in California, and she needed someone in Montana to attend the court proceedings. The relationship between Gustave and the Hagenbaughs is unknown, though he may have been a family friend.

Yet another paper I found was a petition to the court about a parcel of land owned by Charles in Butte, MT. The lot had a home on it and was being rented out for $20 per month. Oddly, there is no record of Charles living in Butte, so he may have purchased the property purely as a speculative investment. The city was a mining boomtown and saw its population quadruple from 1890 to 1910.

Reading through the documents, it was not immediately clear where the home was located. However, a sale announcement in The Anaconda Standard on March 20, 1918 recorded a real estate transaction between C. W. Hagenbaugh to Mrs. Kate Danahey in West Walkerville, MT for $1. Further research revealed that Kate Danahey lived at 120 West Daly Street and that Walkerville is a suburb of Butte. According to a map from 1916, the property contained a building that was divided into several units, presumably rentals. Today, the home appears to have been torn down and the lot vacant.

Empty lot where Charles W. Hagenbaugh once had a rental property in Walkerville, MT. Credit: Google Maps

A final detail in the probate file caught my eye. In one document, Gustave Meyers told the court that when Charles died he had no living relatives or next of kin, except for his wife, to lay claim to his estate. Under United States law, “next of kin” may include a spouse, children, parents, and siblings. If Meyers’ testimony is to be taken literally, Charles had no living relatives other than his wife when he died. This would make sense if, as proposed in Part 2, he was the only child of Civil War veteran and widower, Andrew Jackson Hagenbaugh (b. 1832, d. 1903). For now, that theory appears to be correct.

When I initially set out to place Charles William Hagenbaugh (b. 1862, d. 1913) on our family tree, I never imagined it would be such a frustrating endeavor—one that would culminate in me becoming stuck. Writing this now at the conclusion of the series, I believe I know more of Charles’ life, though I still have a nagging feeling of being stuck.

As genealogists, my father and I are familiar with the process of research that leads nowhere and questions that never resolve with certain answers. Examples include: Why did Andreas Hagenbuch leave Europe for America? What happened to the book, Wahres Christentum, that he gave his son, John? Where did Andreas’ brother, Philipp Jakob, go in the late 1700s? The list goes on and on, leading to feelings of being stuck, just like with Charles.

Of course, there exists no perfect view of the past. The lens through which we peer backwards in time is bounded by what little was saved, recorded, and remembered across the centuries. Yet, while they may be incomplete, we can and should seek to tell the stories of our ancestors. We may never know for sure who Charles’ parents were. However, his gravestone in the San Francisco National Cemetery is no longer simply a name carved into flat, white marble. Charlie—as he called himself—was a person. He lived, and dreamed, and worked. He traveled. He found love and married, and though he had no children, he had a family. That family is ours, and we remember him as one of us.