Settling in Pennsylvania in 1737

Andreas Hagenbuch (b. 1715) and his pregnant wife, Maria Magdalena (Schmutz), landed in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania on September 18, 1737. They had endured many hardships during their months at sea aboard the Charming Nancy, including poor food, disease, and cramped quarters. However, many more challenges lie ahead for the Hagenbuchs.

The Province of Pennsylvania was founded on March 4, 1681. The land in the Americas was given to William Penn (b. 1644) by the English king, Charles II (b. 1630), to settle a £16,000 debt with Penn’s father, Admiral Sir William Penn (b. 1621). Penn had hoped the province would be named “New Wales” or simply “Sylvania.” Instead, the King insisted it be named Pennsylvania (meaning Penn’s Woods) in honor of the Penn family.

William Penn sailed for America and landed in Pennsylvania in 1682. As a Quaker, he valued peace and wanted Pennsylvania to be a safe haven for all people regardless of their religion. True to his beliefs and as a gesture of good will, he signed treaties with the local Lenape Indians and compensated them for their lands.

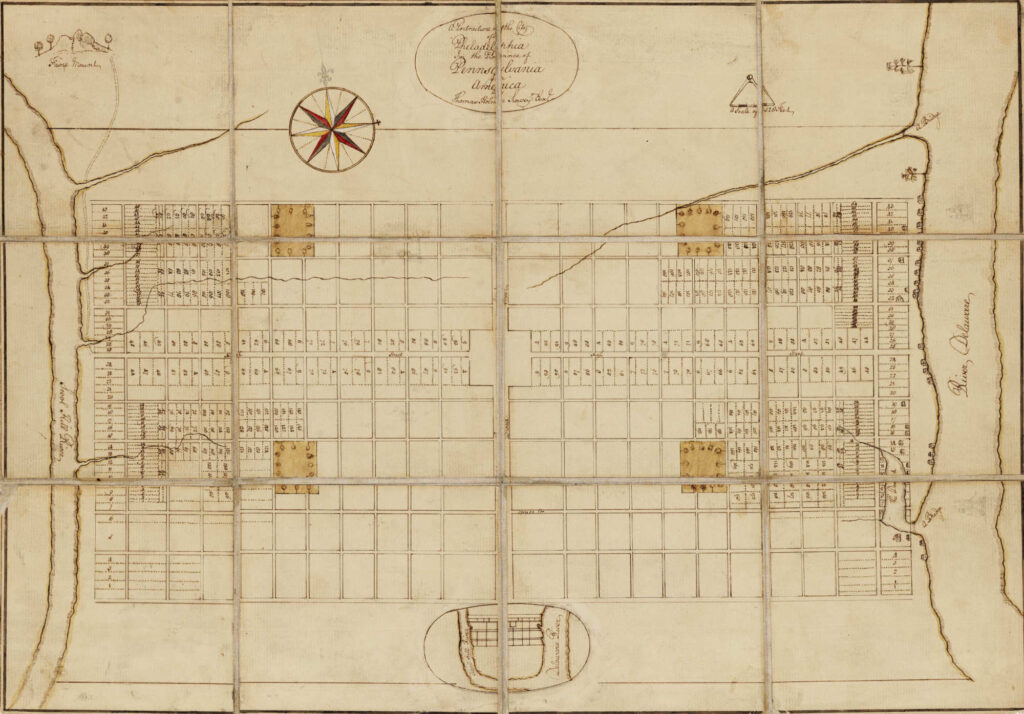

Shortly after arriving, William Penn established Pennsylvania’s first capital, Philadelphia. He wanted it to be less like the cramped, medieval cities of Europe, and more like a rural English village. Philadelphia’s streets were laid out in an orderly grid pattern. The lots were large enough to have gardens and orchards.

While Penn appreciated this design, the early residents of Philadelphia did not. They subdivided their spacious lots and erected new building in the open spaces. By the early 1700s, Philadelphia had become a densely populated, bustling city—something Penn had tried to avoid. He returned to England in 1701 and died in 1718.

When Andreas Hagenbuch and his family arrived in Philadelphia in 1737, its population was about 12,000 people. While this may seem small by today’s standards, the city was actually larger than New York City, which had a population of around 11,000 residents.

By the 1730s, immigrants had been coming to Pennsylvania for five decades. The Penn family and their emissaries actively recruited people from Europe, especially in German speaking areas, to come and settle in the colony. For example, in 1717 Caspar Wistar (b. 1696) emigrated from the Palatine in what is now Germany. He would eventually become one of the wealthiest, self-made people in the colony.

War, religious intolerance, and poor economic opportunities in Europe made immigrating to Pennsylvania an attractive prospect. While starting over in a new place came with its own trouble, it provided many people with the hope of a better life. It also afforded the chance at owning land, something Pennsylvania had in abundance.

On September 19, 1737—the day after Andreas Hagenbuch and his wife arrived in Philadelphia—the infamous Walking Purchase took place. The sale opened up new areas of Pennsylvania’s frontier land for settlement, an event that would directly affect the Hagenbuchs and other immigrants in the years to come.

After William Penn died in 1718, his sons John (b. 1700) and Thomas (b. 1702) took over the proprietorship of Pennsylvania. They claimed that in the 1680s the Lenape had agreed to sell to the Penns a parcel of land beginning around modern day Easton, PA and extending west as far as a person could walk in one and a half days. However, the Lenape leaders had no memory of such an agreement.

By the 1730s, the population of Pennsylvania was rapidly growing, and settlers were already moving into the areas in question. Through the Walking Purchase, the Penns hoped to make these encroaching settlements legal, as well open up additional lands for development.

Begrudgingly, the Lenape leaders agreed to a modified Walking Purchase treaty, with the walk planned to begin near Wrightstown, Pennsylvania. The event began on September 19, 1737. Though it was designated a walk, three excellent runners were chosen to participate: Edward Marshall, Solomon Jennings, and James Yeates. Only Edward Marshall would complete the “walk.” He managed to run (not walk) about 65 miles from Wrightstown to a point near present-day Jim Thorpe, PA. This distance far exceeded the 30 miles that the Lenape expected a man to walk and netted Pennsylvania over 1.2 million acres of new territory for settlement.

Not surprisingly, the Lenape felt cheated by the Penns, tainting the good relations that both parties had previously enjoyed. Anger over the Walking Purchase would come to a head during the years of the French and Indian War (1754–1763) and directly impact frontier families like the Hagenbuchs.

Immigrants saw Pennsylvania’s land as the key to a better life, and what began as a trickle of German-speaking newcomers, quickly became a flood. The Provincial Council of Pennsylvania became concerned by all of the non-English citizens in the colony. In 1727, they passed a resolution requiring all males 16 and older to sign the Oath of Fidelity and Abjuration. The first part required them to disavow other monarchs and pledge allegiance to King George II of Great Britain, while the second asked them to renounce any connection to the Pope. Andreas Hagenbuch and his wife, Maria Magdalena (Schmutz), signed the oaths on October 8, 1737.

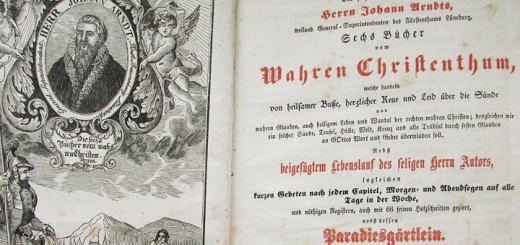

As is commonly done in today’s immigrant communities, many of Pennsylvania’s German immigrants maintained their own traditions and insulated themselves from English culture. The Hagenbuchs would have found like-minded people to live with in Philadelphia or in a nearby village, such as Germantown.

They may have even have had family or friends in the colony. For example, the Hagenbuchs might have known the Romich family (later spelled Romig). Johann Adam Romich (b. 1689), along with his wife Agnes Margaretha (Bernhardt) and children, arrived in Philadelphia in 1732 aboard the Dragon. They heralded from Ittlingen, Germany—only 10 miles from where Andreas and Maria Magdalena were married. Their descendants would later intermarry with the Hagenbuchs.

It was autumn when Andreas and Maria Magdalena arrived in Philadelphia. The couple may have boarded with friends or rented a room, surviving on what money they had brought with them or earned from working odd jobs in the city. We know, however, they were not poor.

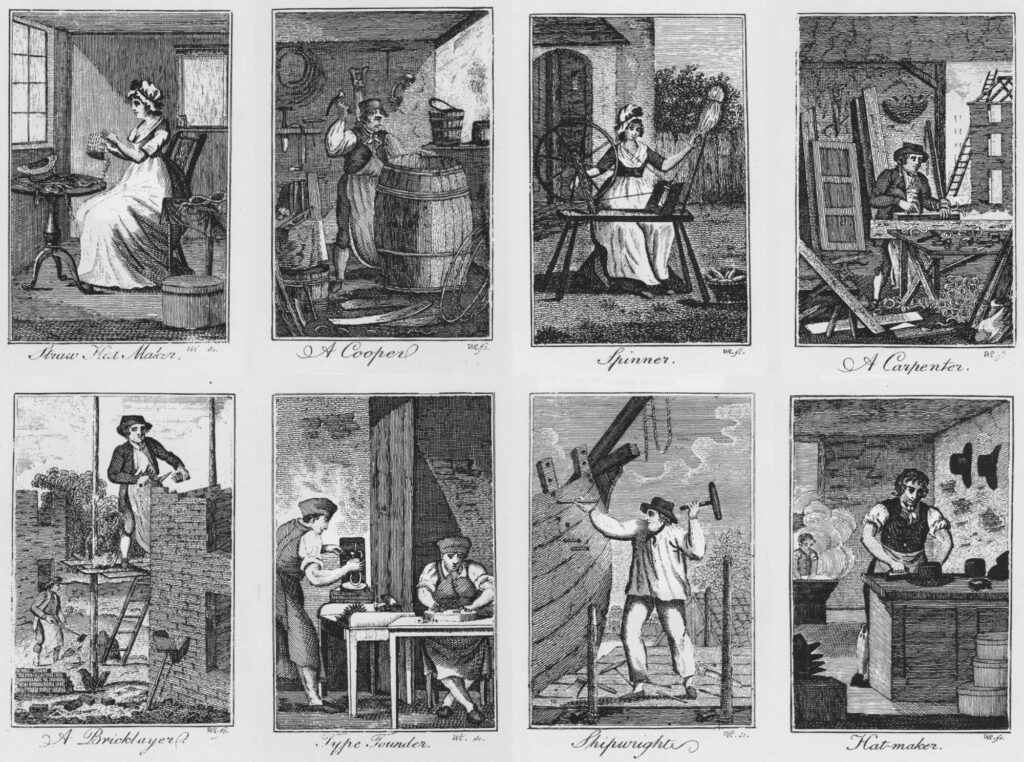

Illustrations of professions from “The Book of Trades, or Library of the Useful Arts” printed in 1804. Credit: Archive.org

Many immigrants arrived in the colonies as indentured servants. Without the means to pay for their own passage, they signed a contract promising to work for their sponsor until the travel costs had been repaid in full. Typically, the term of such contracts was many years. Andreas and Maria Magdalena were indentured to no one, meaning that they had money of their own.

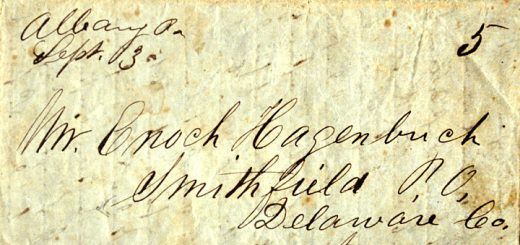

As winter neared, the Hagenbuchs celebrated the birth of their first child, Henry, on December 20, 1737. In the coming months, Andreas would visit the Pennsylvania Land Office at the home of the Proprietors, Thomas and John Penn, in Philadelphia. We know this because on March 25, 1738 Andreas received a warrant for 200 acres of property in the Allemaengel—a region in what is today Albany Township, Berks County, PA. Less than six months after landing in America, the Hagenbuchs had a place to build their home.

The next article in this series will explore Andreas Hagenbuch’s efforts to establish a homestead in the Allemaengel at the edge of Pennsylvania’s frontier.

This article was updated on April 22, 2025 to included improved pictures, new information, and details about Henry Hagenbuch being born in America.

Hello, I would like to receive any updates you may have on the Hagenbuch’s. I am Jane Hagan and one of my ancestors married Josephine Bernhard. We think we descend from Edward Hagan, who settled in what was Lancaster County, PA in 1748. The county became York in 1749 and Adams in 1800. We are searching for information about the parents of Edward Hagan, where he came from. The names Hagan and Hagenbuch are very close, and then we have a Hagan-Bernhard marriage in 1878. (James Alexander Hagan, 1852-1927 (age 75), our direct ancestor, m. Josephine (Josie) Bernhard in 1878. Maybe they came from the same regions as the Bernhard and Hagenbuch.