Searching for Andreas Hagenbuch’s House: Part 2

In part one of this series, three theories for the possible location of Andreas Hagenbuch’s house were proposed. In the second and final installment, the third and most likely theory will be explored in detail.

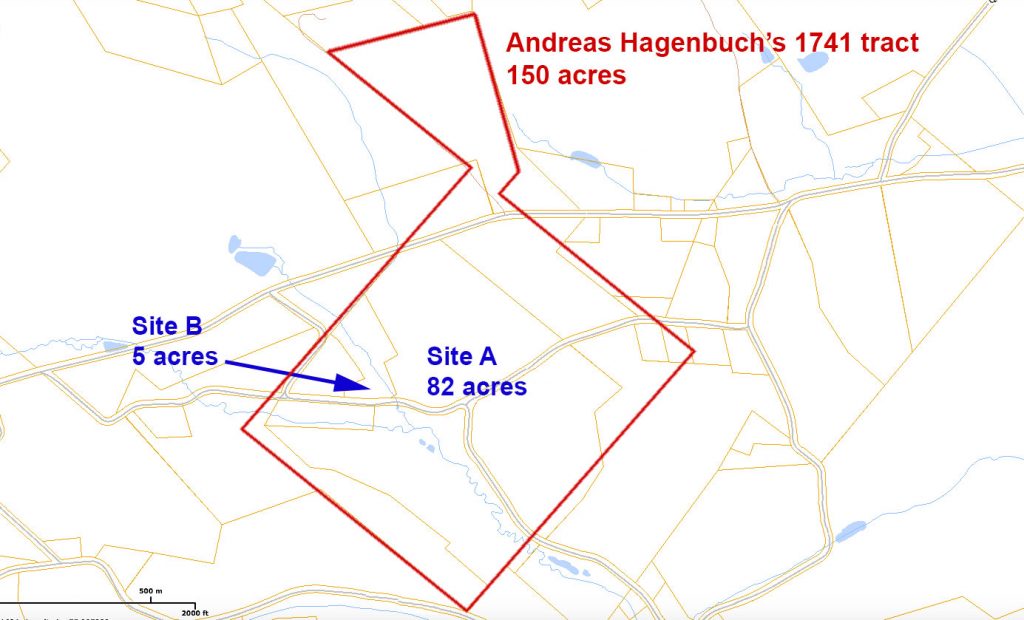

It is known that Andreas Hagenbuch acquired 150 acres of land in Albany Township, Berks County, Pennsylvania in 1741. Here, he established a homestead. The exact location of the tract is known with a high degree of certainty, though today it has been subdivided into a number of smaller properties.

The largest parcel within the original 150 acre tract is 82 acres (Site A on the below diagram). On this can be found an old cemetery with one Hagenbuch stone dating from 1781, as well as a number of buildings from the 19th century. One of these is the bacon stone farmhouse built by Michael Hagenbuch (b. 1805, d. 1855) in 1851. Yet, no evidence of the 18th century home constructed by Andreas has been found.

One theory suggests that his home was located someplace else. The reasoning for this begins with the creek shown on the original 1741 land survey. Fresh water was needed by the Hagenbuchs, their livestock, and the distillery they ran. Andreas likely established his homestead near the creek.

Watercourses change over time. However, a creek still runs through the 82 acre parcel. It also flows through an adjoining five acre property (Site B on the below diagram) that was once part of the original 150 tract too. Curiously, Site B contains an older house, banked barn, and several outbuildings. Might this actually be where Andreas first built his home?

To understand the origin of the five acre Site B, it is necessary to trace the history of Andreas Hagenbuch’s 150 acre homestead. A Berks County deed search returns the 1782 transfer of the homestead to his son, Michael (b. 1746, d. 1809). The deed defines the boundaries of the tract, confirms it being 150 acres, and also mentions that it contains a “messuage.”

According to Merriam-Webster, a messuage is defined as a “a dwelling house with the adjacent buildings…” So, from the deed it is possible to know that in 1782 the original 150 tract had not been subdivided and contained a home with outbuildings. At a minimum, these would have included a house, barn, and distillery.

The next clue comes from 1809 when Michael died without a will. His estate was inventoried, and this specifically notes “one messuage” along with two tracts of land totaling about 300 acres. While Michael had added additional land to the homestead, it would seem that most buildings were clustered in one general area.

After Michael’s death, his son Jacob (b. 1777, d. 1842) took control of the homestead. Like his father, Jacob died without a will and here is where things get interesting. During the estate proceedings, which were conducted between 1842 and 1843, it was decided that Jacob’s lands should be divided into three parcels. These were as follows:

- 179 acres with a messuage

- 10 acres with a messuage and tannery, as well as 29 acres of nearby woods

- 129 acres of land with no structures

Because the 129 acre parcel lacked structures, it can be disregarded as the location of Andreas Hagenbuch’s house. The question then arises: which was developed first, the 179 acre parcel or the 10 acre one? The answer will point to the most likely site of Andreas’s house.

Determining the location of these tracts is challenging. One clue is the adjoining property owners. The 179 acre parcel mentions that it abuts the lands of Robert Stapleton. The Stapletons had owned land on the northeast side of the Hagenbuch homestead since the time of Andreas. Noting its large size, it is probable that the 179 acre parcel included much of the 150 acre original lot.

The 10 acre tract only abutted three properties: the 179 acre parcel, land owned by Jacob Petry, and others held by Jacob Smith. It is known that the Petry family owned land along the northwest side of the Hagenbuch property. Knowing the Petrys were to the west and the Stapletons to the east, it would seem that the 10 acre tract was along the western side of the 179 acre parcel.

Not surprisingly, Site B is also to the west of Site A. Could these modern properties have been created after the death of Jacob? A deed search on Site B reveals that not long ago it was part of the 10 acre tract. These 10 acres can be traced all of the way to 1876 when a deed mentions that it was sold by the representatives of Isaac Knepper and payment was made to Sarah Brobst. So it appears that Site B once matched the size and relative location of the 10 acres documented as having a messuage and tannery in 1842.

The tannery is another fascinating clue worth exploring further. It is known that Michael (b. 1746) and Jacob (b. 1777) were both tanners. Assuming the tannery, which requires animal hides, was near a barn, it is likely that the operation was located close to the site of the original homestead. Indeed, Site B does include a barn, and may very well have been where the family first established themselves and their tannery.

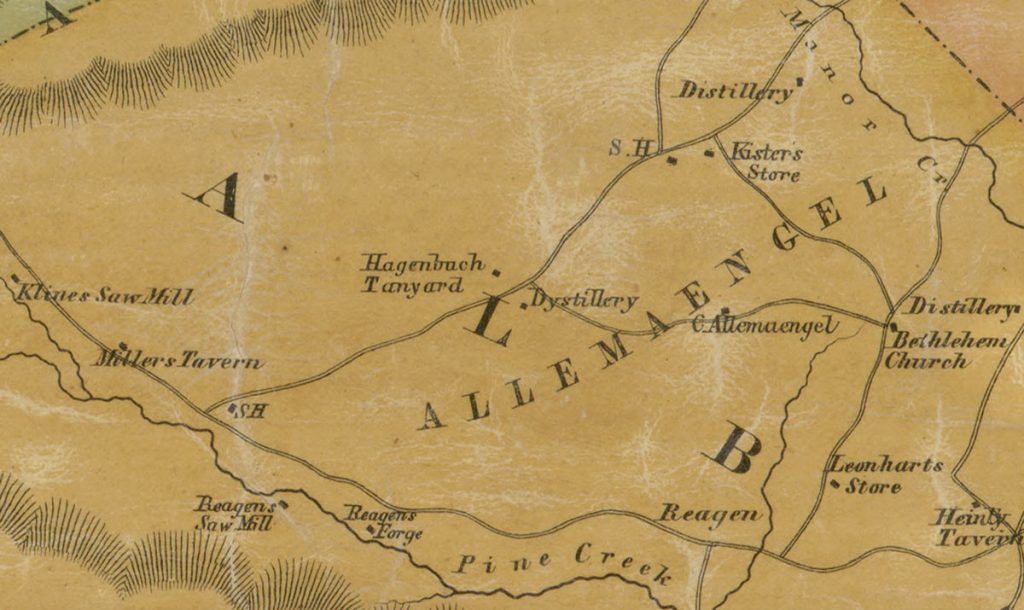

Still, one is left wondering: what structures were part of the messuage noted on the 179 acres around Site A? As previously discussed, Timothy Hagenbuch’s (b. 1804, d. 1852) schoolhouse was located there and was likely constructed in the early 1800s. Additional information comes from a map dated 1854. This happens to show the Hagenbuch tannery (Site B) and a distillery located a short distance to the east. Could it be that the Hagenbuch’s distillery along with Timothy’s schoolhouse were part of another cluster of buildings located near Site A? More research into this question is needed.

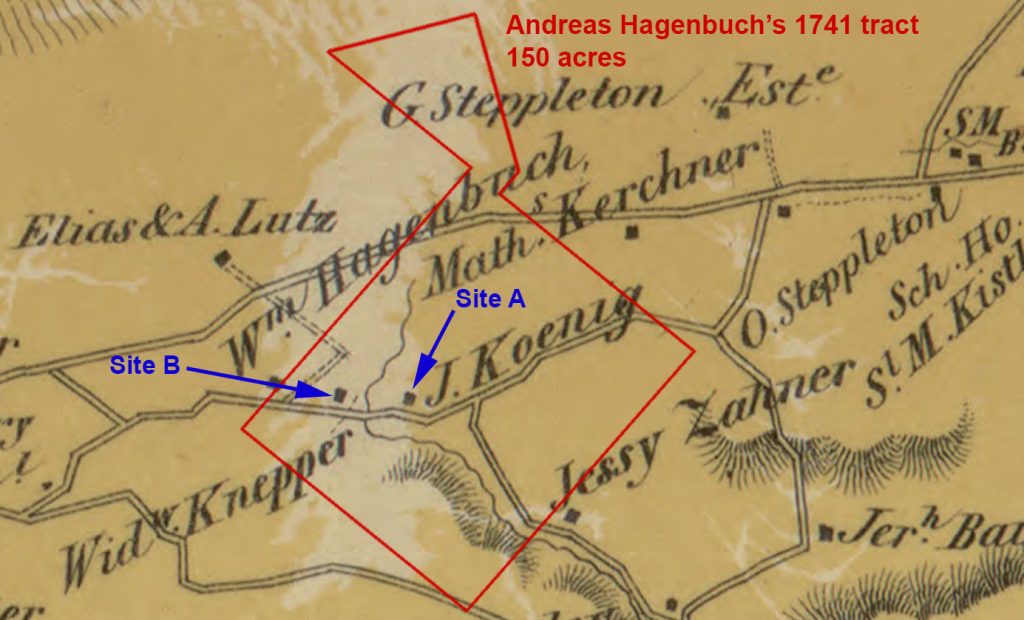

One final clue is found on a landholder’s map from 1860. This shows only two houses located within the bounds of the original Hagenbuch property (See the below diagram). John Koenig is shown living near Site A and Widow Knepper by Site B. Who are these people?

When Jacob Hagenbuch died in 1842, his son Michael (b. 1805, d. 1855) acquired several of the homestead properties. Yet, just over a decade later in 1855, Michael himself died. The stone farmhouse he built in 1851, barn, and nearby lands left the family and were being used by the Koenigs in 1861.

The Widow Knepper is none other than the wife of Isaac Knepper (b. 1815, d. 1856), Sarah “Hagenbuch” Knepper Brobst (b. 1817, d. 1904) who earlier appeared on the deed search of Site B. Sarah was the sister of Michael Hagenbuch (b. 1805). It would seem that after the death of their father in 1842, Sarah and her husband lived at the house with the tannery on Site B, while Michael built a new house, summer kitchen, and barn on the larger Site A. After Isaac Knepper’s death in 1856, Sarah lived alone for a while, eventually remarrying a Brobst (possibly Daniel Nathan Brobst, b. 1801, d. 1876)

In summary, the proposed timeline of Andreas Hagenbuch’s homestead is as follows:

- 1741 – Andreas (b. 1711) acquires 150 acres of land and builds his homestead on what is now known as Site B. A distillery and cemetery are constructed nearby on Site A.

- 1782 – Michael Hagenbuch (b. 1746) acquires the property and adds a tannery near the original group of homestead buildings at Site B.

- 1809 – Jacob Hagenbuch (b. 1777) acquires the property. Additional buildings, such as Timothy Hagenbuch’s schoolhouse are built near the distillery on Site A.

- 1842 – Upon Jacob’s death the land is divided. Sarah “Hagenbuch” Knepper Brobst lives in the property containing the tannery (Site B). Michael Hagenbuch (b. 1805) constructs a new home, barn, and summer kitchen near the schoolhouse (Site A).

- 1855 – Michael’s house and land are sold out of the family.

- 1876 – Sarah’s house and land are sold out of the family.

After locating and researching Site B, a visit was made to the property for a closer look of what was there. Compared to Michael’s 1851 farmhouse, the home on Site B is located closer to a road and running water.

The house also has a smaller footprint and an unusual design. The ground floor is made of stone that is rougher than that used in Michael’s farmhouse. Presently, this serves as a basement. Above it are two stories built from logs and covered with siding. Might the ground floor which contains windows and several doors have once been part of a smaller stone building? Future research will be necessary to determine this.

In addition to several outbuildings, the property has a banked barn constructed in the Sweitzer style. This type of barn was built into an earthen bank, enabling easy access to the first and second levels. The Sweitzer style was commonly used by immigrants from Germany and Switzerland in the 18th and early 19th centuries. It has an asymmetrical gabled end, created by the roof extending beyond the foundation on one side. This creates additional space on the second level and shelter for the livestock stabled on the first.

A final fascinating thought comes from the property’s current owners. According to them, the ground on the lot is uneven and contains several sunken areas. Might these be the remnants of other structures from the 18th century?

While it appears that Andreas Hagenbuch’s original log house does not remain, it is exciting to think that Site B might actually be where this stood. At the very least, Site B and its buildings predate many of those on Site A. It is hoped that this discovery will open new avenues for understanding the development of the homestead and the generations of Hagenbuchs who lived there.