Saving Recipes: Harold Sechler and the Chef Boyardee Story

Harold F. Sechler (b. 1923, d. 2018), my first cousin twice removed, saved recipes. He cut them from newspapers, wrote them on scraps of paper, and held onto promotional recipe booklets. His collection of cooking instructions appears to have been started by his Aunt Grace (Sechler) Cromis (b. 1888, d. 1973)—who raised him—but was added to after her death. Aunt Grace was the sibling of Harold’s father, John McWilliams Sechler (b. 1885, d. 1928), and of my great grandmother, Hannah (Sechler) Hagenbuch (b. 1889, d. 1967).

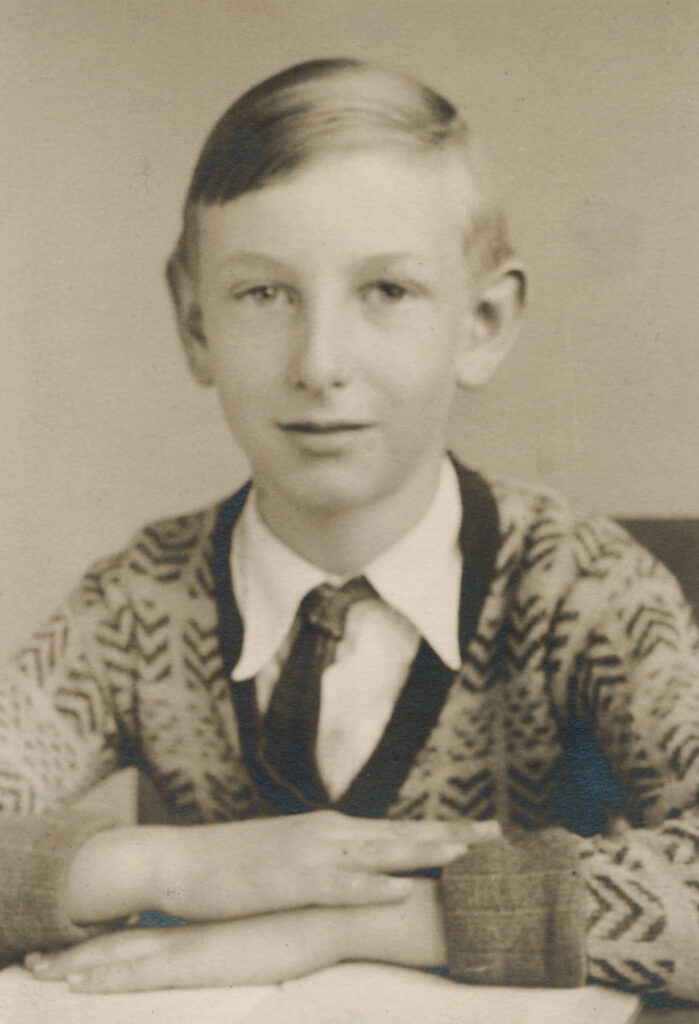

Recently, I had a chance to look through a box that contained Harold’s recipes. While it also held a few photographs, such as a nice school picture of him, most of the contents were related to food. I have no idea how many of these recipes Harold actually made. However, they do provide a sense of what he was eating. Here are just a few that I found:

- Lois’ Company Best Pickles (another recipe lists her as Lois Oswald)

- Quince Spread

- Barbecued Chicken

- Pumpkin Muffins

- Fruit Rolls

- Baked Navy Beans

- Honey Peanut Butter Candy

- Baled Hay

- Green Tomato Mincemeat

- Whole Wheat Pancakes

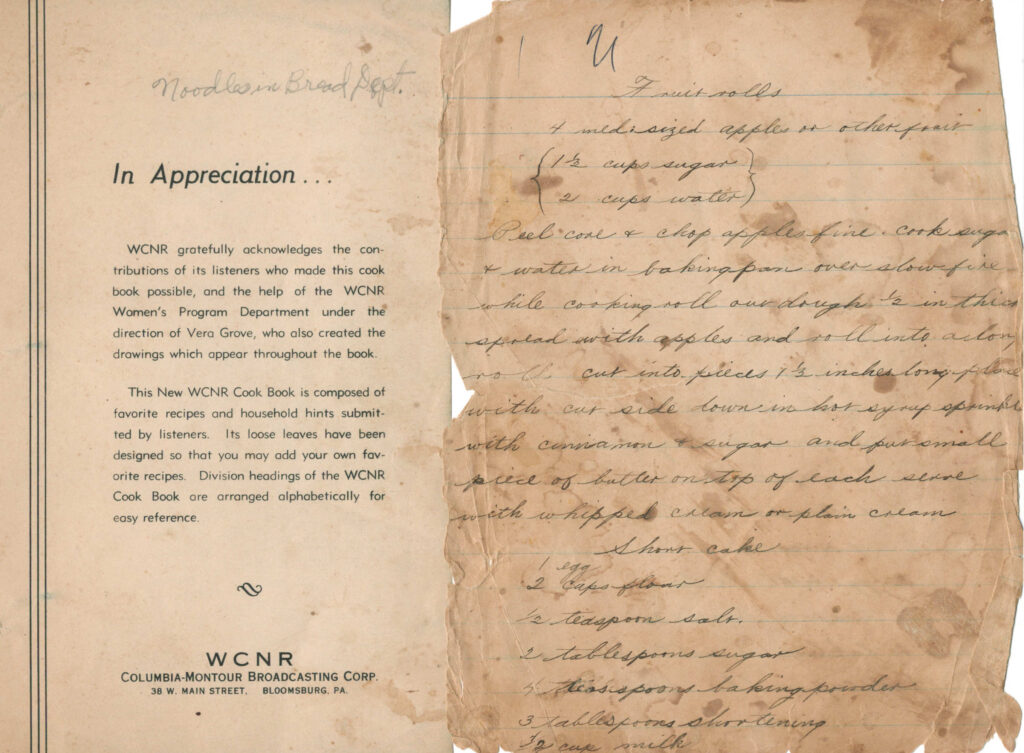

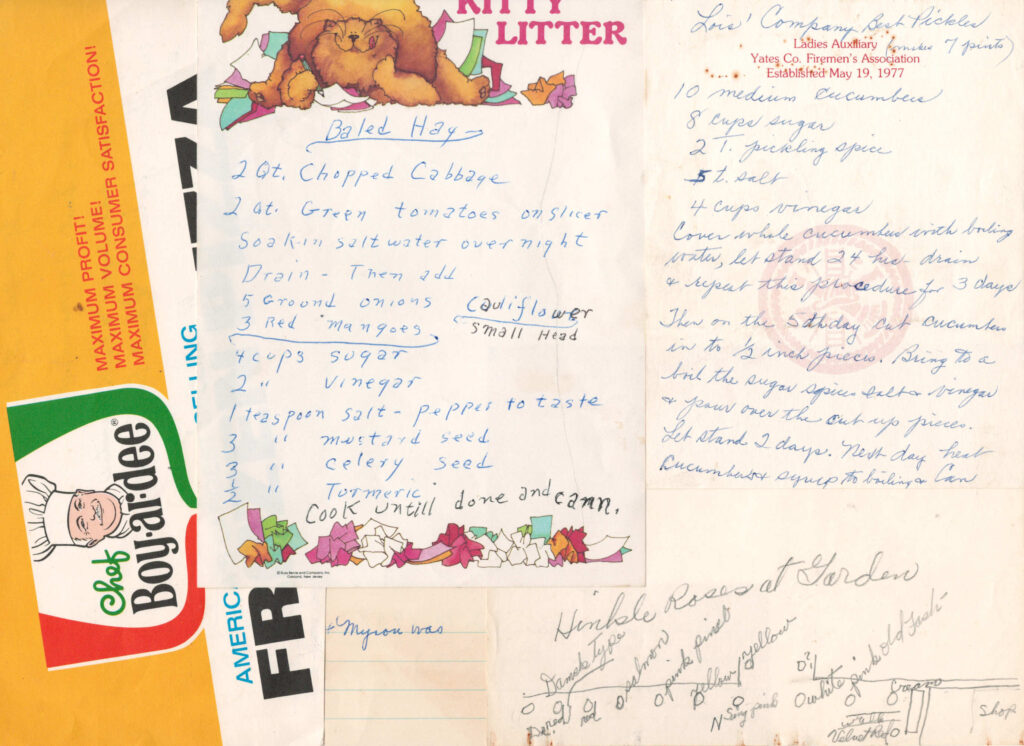

The most substantial item in the box was the WCNR Cookbook. WCNR was once an AM radio station broadcasting from Bloomsburg, Pennsylvania. Stuffed into the cookbook were the pages of an old notebook inscribed with more recipes. Their author appears to have been Aunt Grace. On another scrap of paper, I found a hand-drawn diagram for “Hinkle Roses at Garden.” Finally, on the back of a recipe was an unfinished note that began with “Myron was.” We know that Myron Cromis was the son of Aunt Grace and lived with his cousin, Harold, until the end of his life. Yet, one can only wonder what Harold stopped short of saying here.

Recipes are an important part of family history. Over the years, we have featured numerous recipes on this site, some of which hold memories of relatives or of gatherings from long ago. Others date from an even earlier time and were enjoyed by our Hagenbuch ancestors.

Page from the WCNR Cookbook (left) and a handwritten recipe for fruit rolls placed within it (right)

At one time, recipes were part of a folk tradition, passed down by learning from parents and grandparents in the kitchen. Sometimes they were written down; other times they were not. Then came printed recipes, mass produced and disseminated in newspapers, books, and pamphlets. Yes, great grandma had a terrific cookie recipe, but it was easier to follow the one from a cookbook. Finally, everything went online and many millions of recipes could be easily searched and found in an instant. Who needs all that paper when the internet has more variety and is faster to use?

Like other artifacts, recipes must be saved and preserved—yes even ones from the internet! A favorite recipe can be bookmarked online, but what happens when the website where it is hosted goes away? My wife, Sara, and I have experienced this problem first hand! Printing out the recipe or saving it to a digital file can ensure it is available for years to come.

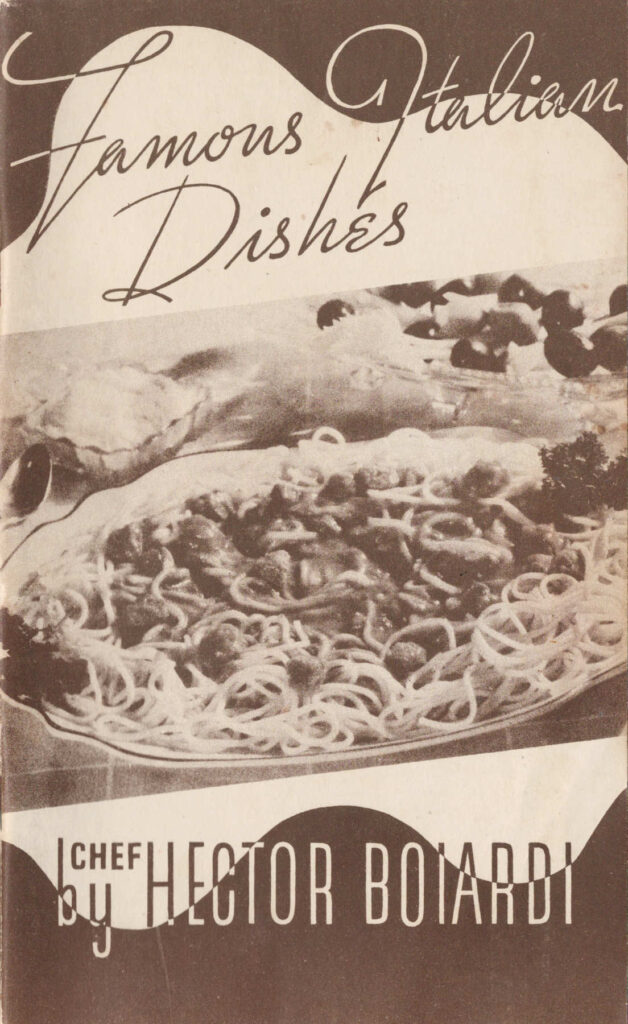

One of the most interesting items found among Harold’s recipes was a booklet titled Famous Italian Dishes written by Chef Hector Boiardi. Yes, this is none other than Chef Boyardee, whose Italian sauces, meal kits, and other ingredients started to be sold to American consumers during the late 1920s. The booklet is a 1938 promotional piece that includes recipes for Italian dishes that make use of Chef Boyardee’s ingredients.

Famous Italian Dishes also highlights some of the brand’s story, which I knew nothing about. Hector Boiardi got his start as a chef for some of New York City’s most important hotels, like the Ritz-Carlton and the Plaza. He eventually moved to Cleveland, Ohio, and opened his own restaurant, Il Giardino d’Italia, in 1924. A few years later, he started to bottle and sell his sauces to grocery stores. The brand was changed from the Boiardi family name to a phonetic spelling, Boy-Ar-Dee, to aid consumers with pronouncing it. Eventually, the hyphens were removed, and the brand became known as Chef Boyardee.

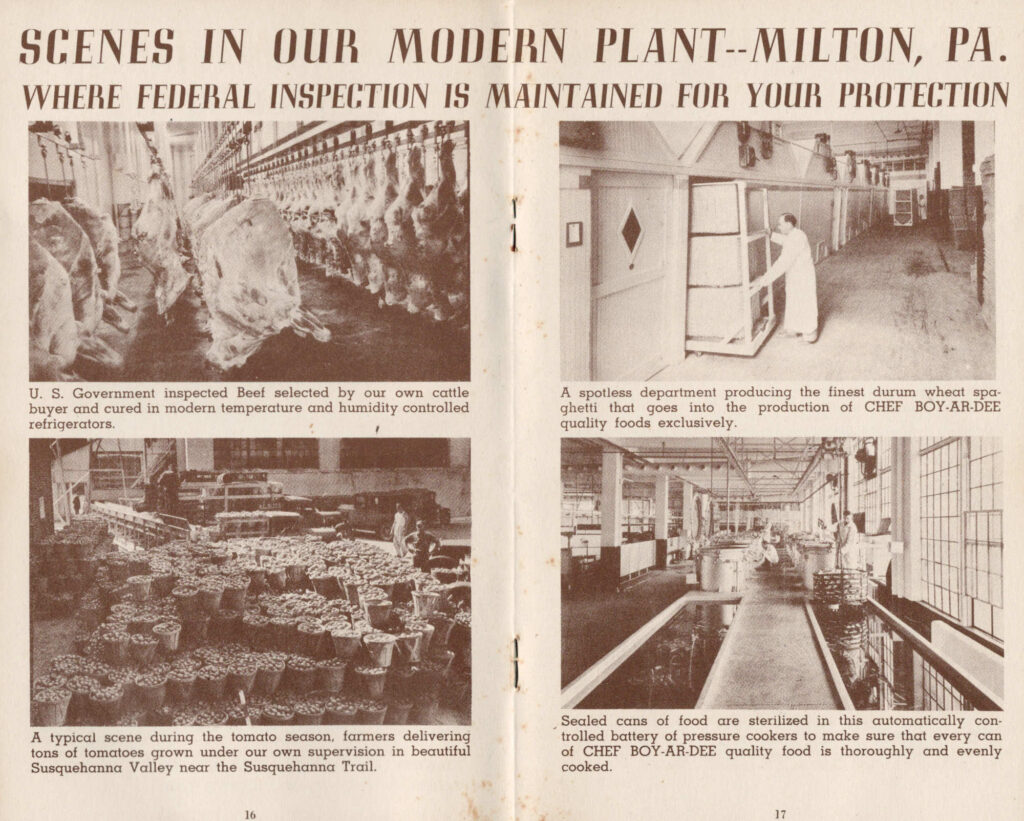

Demand for its products grew, forcing the company to find a location for a larger facility. Milton, PA was chosen, since it was surrounded by rich farmland and was closer to East Coast markets such as New York City. In 1938, an old silk mill on the southern end of Milton was converted into the new home of Chef Boyardee. This occasion led to the printing of the booklet Famous Italian Dishes, which touts the facility. The brand’s products are still produced in Milton today, though it is now owned by Conagra.

Prior to discovering the booklet, I had no idea that Chef Boyardee’s products were made in Milton—an area connected to the Hagenbuch family. When I mentioned this to my father, Mark, he recounted how as a teenager in the late 1960s he had a job loading tomatoes into a truck that was bound for the Chef Boyardee plant. The tomato picking happened on the farm of George Hower, Jr.

At the same time, my grandfather, Homer Hagenbuch (b. 1916, d. 2012), was working evenings for Kepler Farms. They also grew tomatoes, and he would drive them to the Chef Boyardee plant. Sometimes the tomato trucks from Hower’s farm—the ones that my father had loaded earlier in the day—would be pulling into the plant when my grandfather was arriving with his load from Kepler’s.

Additionally, my father mentioned that he and my mother, Linda, shared a Chef Boyardee frozen pizza on their first date in 1972. And, some of our extended family was connected with Chef Boyardee as well, including Clyde Hagenbuch (b. 1920, d. 2012) who worked there for almost twenty years.

Scenes from the newly opened Chef Boyardee plant in Milton, PA as depicted in “Famous Italian Dishes”, 1938

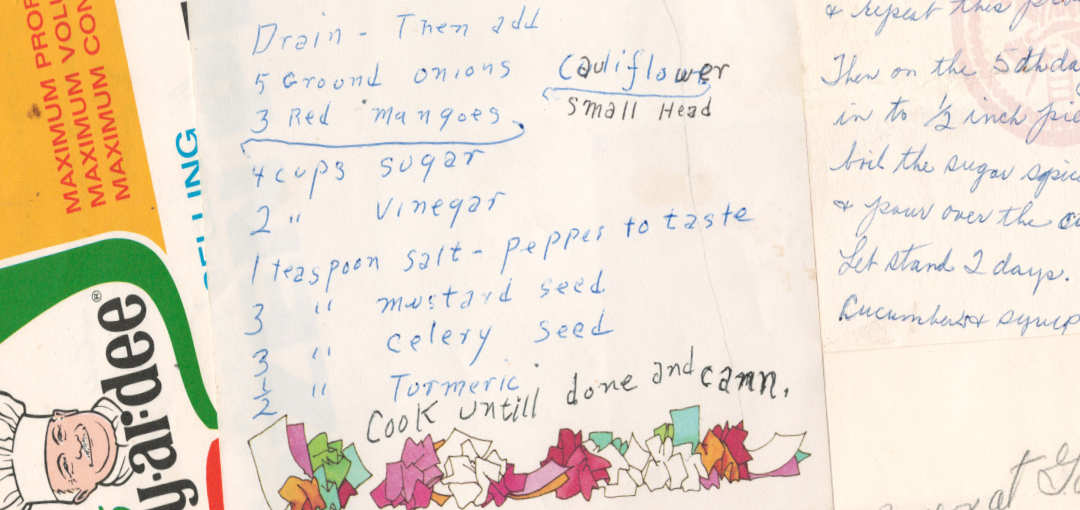

I am sure many in our family have tried Chef Boyardee products over the decades. We know that Harold Sechler certainly did. Not only did he have the Famous Italian Dishes booklet with his things, he also hand wrote numerous recipes on the back of packaging from Chef Boyardee frozen pizzas!

I can’t say if, or when, I will be making any of the recipes that Harold saved. That said, I am glad he tucked them away, so that we might get a glimpse of what his family enjoyed cooking and eating. Of course, should I decide to try any of these delicacies, rest assured, I will share the results here.

Marcia and I met and talked awhile with Hector’s grandson at a party when we lived in Milton in 1966. He was very down-to-earth and friendly. That was the first we knew that the name was spelled Boiardi. I believe he told us a little bit of his family history then too.

Another great article, Andrew!

Thanks, Uncle Bob! It was great seeing you and Aunt Marcia yesterday too.