Revisiting Enoch Hagenbuch’s Written History

In the summer of 2015, this site published a series of four articles about Enoch Hagenbuch (b. 1814) and his written history (Enoch Hagenbuch: Early Family Historian, Parts 1, 2, 3, and 4). Enoch wrote a manuscript in 1884 that lists memories, stories, and family members’ names, going all the way back to Andreas in the eighteenth century. The abridged version is reproduced in this article series, yet there is also an unabridged version that exists with even more valuable family information.

A few months ago, I offered to help my husband, Andrew Hagenbuch, add all of these names into the Beechroots.com database. I’m proud to announce that we’ve now added all of the family members included in Enoch’s unabridged history, totaling over 270 names! Enoch often included birth places, burial locations, and stories about each person. I’ve done my best to include as much information as possible about each person to build out our family tree on Beechroots.

Considering each person individually led down a number of rabbit holes. I added the names manually and also looked up the Hagenbuchs on Findagrave.com to find additional details about their dates, birth places, burial places, and family. Frequently, Findagrave will link up to other family, showing the profiles of spouses, children, and siblings. It’s possible to continue on an endless journey of genealogical investigation, clicking from page to page. I mostly stuck to the task at hand (the names listed in Enoch’s history). Otherwise, this Beechroots data project would still not be completed!

Reading this history and inputting data has the potential to be a mechanical task. However, it’s much more intriguing to read between the lines and consider what the style and details of Enoch’s manuscript reveal about him as a person. Why did he include certain stories and pieces of information? What did he consider important enough to relay in his book, to share with the future generations of Hagenbuchs? I’d like to highlight a few tidbits for your contemplation.

In the preface to the history, Enoch shares his thoughts concerning Hagenbuch character and his goals in recording this genealogical information:

The Hagenbuchs are not among the distinguished men and women of our beloved land. They are, nevertheless, almost all of them honest, temperate and industrious, and may be counted among our best citizens…The author, in presenting this book to the public, hopes that those who peruse its pages will do honor to the Hagenbuch character, and seek to emulate their heroic actions.

Was there not yet a “distinguished” family member, or did he not know of them? He also claims to “have never been able to find the name on prison or pauper catalogue,” yet we know that after Enoch’s death, Isaac W. Hagenbuch (b. 1852) was sentenced to serve time in Eastern State Penitentiary. It seems that the Hagenbuchs of Enoch’s time were a wholesome clan, or perhaps his comments speak to his point of view and his relationships with his family.

He also writes about the cost of living and the physically demanding work during his lifetime. He “burned charcoal at $18.00 per month” and “paid $1.40 for a bushel of rye, chopped cord-wood for 25 cts per cord, cradled in the harvest field for 33 1/3 cts. per day, and had to put more hours into a day than is done now.” What would he say about our current jobs and hours put into a day of work?

Log home built by Elias Comstock in the 1830s. Unlike Nathan Hagenbuch’s house, this one uses hewed logs. Credit: Wikipedia.com/Jetmound

Enoch goes into great detail about Nathan Hagenbuch (b. 1811) and Rebecca (Stein) Hagenbuch’s (b. 1812) log home. Since their house is likely no longer standing, it is quite interesting to be able to visualize its construction and gain more information about how homes were built in the early nineteenth century.

He bought six acres of land, and on it he built a log house of unhewed logs. The roof was made of clapboards four feet long, laid double, so the top course, broke joints with the first, held down by a log, and so on till the roof was completed. The chimney was built outside the building at one end, and a hole cut through the logs for a fireplace.

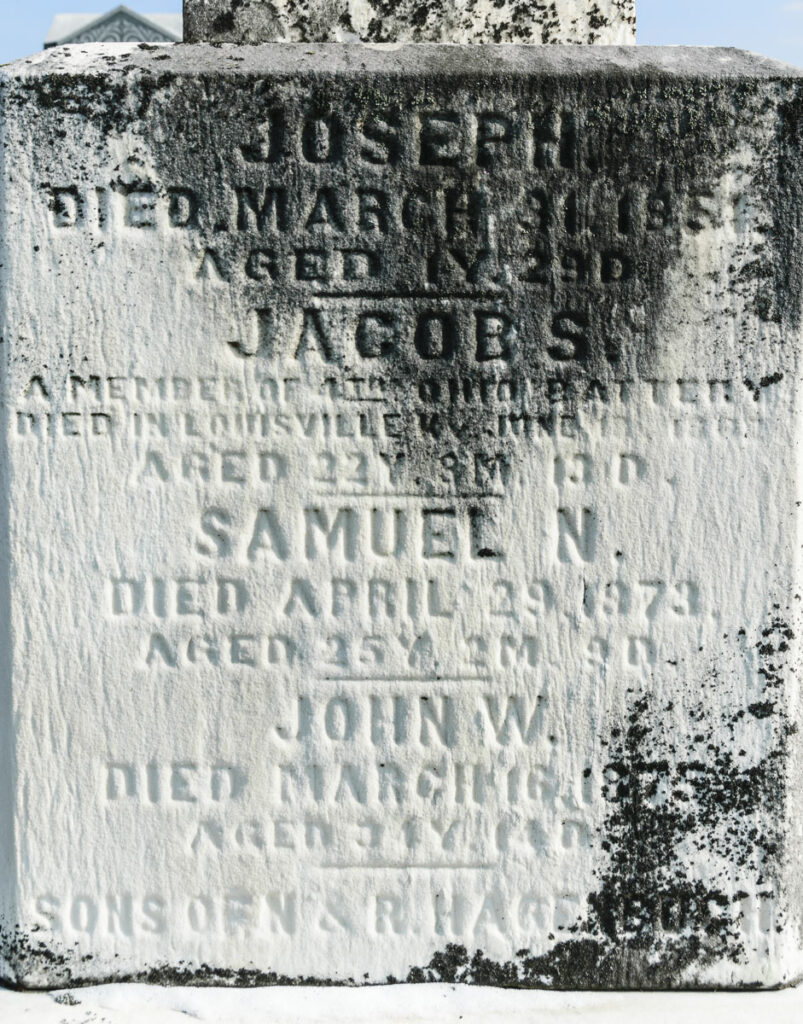

Perhaps most captivating are the personal stories about Hagenbuchs past. He writes of the poignant loss of Jacob S. Hagenbuch (b. 1839). Jacob joined the 4th Ohio Battery in 1861 and traveled to Tennessee.

The hardships he endured did not agree with him and health began to fail, and on Mar. 2 1862, he was taken to Nashville hospital. Remained there until June 16. He then left for home, and got as far as Louisville, Ky., but could go no farther and was taken to the hospital and died there June 18, 1862, aged 22 yrs., 8 m., 13 d. His father brought home his remains, and all that was earthly was consigned to mother earth at the family cemetery in Shelby.

Enoch shares personal anecdotes about his immediate family and himself. Of his first vote in an election (writing in the third person):

His first vote at a Presidential election was for Martin Van Buren in 1836.

This was clearly a noteworthy and exciting life event. He also is quite proud of his daughters Lydia (Hagenbuch) Watt (b. 1837) and Harriet (Hagenbuch) Erb (b. 1835) and their resourcefulness:

In the winter of 1853, in the absence of father and brothers, these girls attacked and killed a deer on the ice of the creek running by their home.

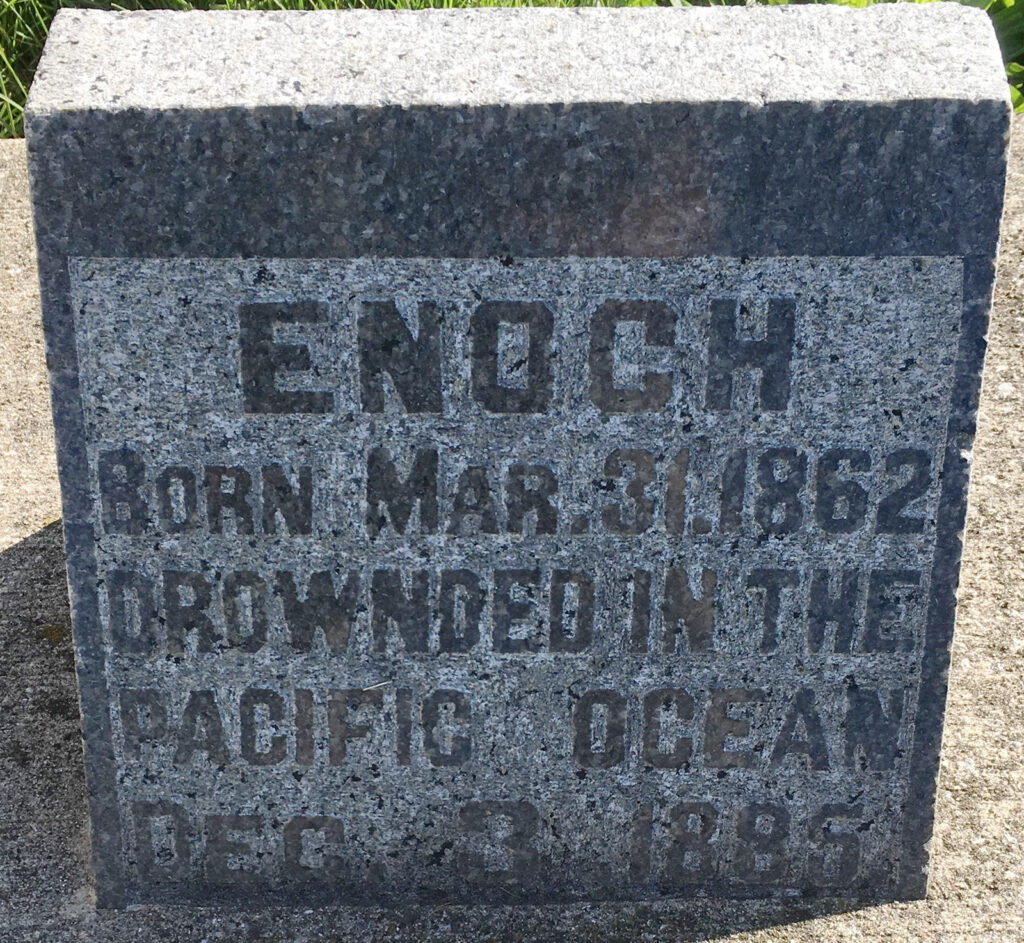

He writes of Lydia’s son, Enoch H. Watt (b. 1862), and his untimely death:

He hired out as a hand on a vessel called the ‘Emma,’ employed on the Pacific Ocean catching sea lions. About Nov. 4, 1885, while out on a cruise, a severe storm overtook them, overturned the vessel, and on the 8th his body was discovered on the shore, and there in the cemetery, he lies buried.

And of his youngest daughter, Malinda (Hagenbuch) Ferry (b. 1851):

At twenty years of age she weighed 260 pounds, and very active at almost everything. At thirty-three years of age she weighed 309 pounds.

Of course, all of these stories are valuable details in themselves. However, more interesting is why Enoch chose to select and write them down for posterity. By which stories should a person be remembered? The only details we know of Malinda are concerning her birth, death, and weight. Was Enoch proud of her, or ashamed, or something else? These questions can be pondered, but will likely remain unanswered.

Enoch ends his history with a personal message. As he warns in it, we have found errors in his manuscript. Some we have been able to uncover and correct, perhaps, as he said, making “an improvement on it.” Regardless, we are most grateful for these details and a glimpse into the life of our ancestor.

Now, I say good-bye. God bless the whole fraternity, and may everyone answer the design of the Creator in his life and life-work. Now, don’t find fault with what I have written, for I am sensible of many errors in this memorial, but hope some good friend will make an improvement on it. Yours for the right always, Enoch Hagenbuch

Watch for a future article about the poetry Enoch includes in his genealogical history.

Thanks Sara….I’m glad you are getting some well earned credit for the contributions to this web site. I am sure Mark and Andrew welcome your dedication.

Great job Sara! This explains the couple tweaks you made to my entries in the site. 🙂