Painting Portraits of Our Family, Part 1

An often heard quote states: “Find a job you enjoy doing and you won’t have to work a day in your life.”

Most people’s first jobs are out of necessity and aren’t what they plan as their life’s career. My first paid jobs when I was 14 years old were working for a local farmer hoeing fields and picking tomatoes, working in a local general store, and as church organist at Oak Grove Lutheran Church—all at the same time—until I went off to college in 1971. During my time in college, I worked in the cafeteria and at a local restaurant. These were all jobs of necessity to have funds to prepare myself for my career in education, teaching, and school administration.

There have been several articles written about the jobs that Andreas Hagenbuch (b. 1715) and his four sons had. However, the times in which they lived were much different than the twentieth century when I was deciding my career path. Were their jobs more works of necessity or careers that they chose? We’ll never know the answer to this with certainty, but we can make some logical conclusions.

Portraits of the 18th century often depict people holding or pointing to something that describes their career or position. Their clothing in these portraits is also often descriptive of their job or interest. Take for example, George and Martha Washington. George is frequently depicted in his military uniform or standing with a globe or even having a battle scene behind him. A famous portrait of the couple together, painted in 1789 by artist Edward Savage, depicts them with their grandchildren which speaks to the importance of family. Soon-to-be first president Washington is wearing his military uniform, although he was not serving in any military capacity at that time. The papers under his hand represent his administrative ability, both in the military and government. Martha Washington is dressed in fine clothing and holding a fan befitting her station in life. And, she is pointing to a map of where the “President’s House,” what we now call the White House, will eventually be built. So, the two of them have depictions of family, military, government, status, and home.

George and Martha Washington with their family by Edward Savage, 1789. Credit: National Gallery of Art

What if there had been portraits painted of Andreas, his wives, and his children? What would they depict?

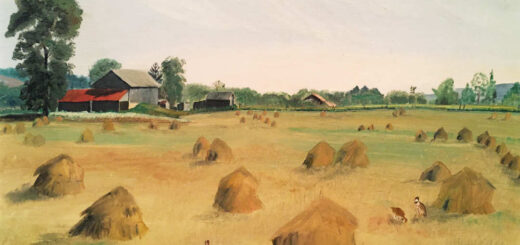

We don’t know what Andreas brought to America other than his second wife, his infant son Henry, and the drive to make a new life in Pennsylvania. We don’t know what skills he had when he came here. We don’t know what his job or career was when he lived just north of what is now Stuttgart, Germany. But, he must have had some skills or learned quickly about constructing a shelter for his family and creating a living from farming. We know that he had a distilling business, a tanning business, and a fiber arts business. To create these businesses he had to be a farmer. He would have grown fruits and rye for whisky and brandy, raised animals for food and hides, and cultivated flax for linen.

It is also quite evident he was savvy in purchasing property and loaning money with an assigned interest. He was a sort of “banker and land speculator.” Additionally, he helped his sons begin businesses and possibly helped the sons to keep those businesses going. A few of his daughters were certainly involved in the fiber arts business as evidenced by the linen that was given to several of them in his will. And, he may have had some hand in making marriage matches for his children as they did marry into solid, local families. All of this is evidence that he was the family patriarch, or as he is known still in Albany Township by some of the local historians, the “go to guy.”

Andreas may have arrived in America with cash in late September of 1737. We don’t know. But, we do know that he had the personal characteristics that were the impetus behind the small empire he created on the frontier of Pennsylvania, the Allemangel. He must have been endowed with both the physical and mental strength to construct a building that was termed a safe house—one where the neighbors could go when danger occurred during the unsettling years of the French and Indian War. His neighbors trusted him, his family was large (3 wives and 12 children living to adulthood), and his legacy lives on. His first jobs were of necessity to become a successful settler in a wild land. Later these evolved into a career where he was respected because of his wisdom and the material wealth he amassed.

In an imaginary portrait of Andreas, we would expect to see a depiction of the Berks County farm and Blue Mountains behind a man who is physically strong and confident. The farm would have some animals grazing among some fruit trees. He would be pointing to papers on a table where also would lay a Pennsylvania rifle. And, off to one side would be hanging a sheaf of rye for distilling and a bundle of flax for making linen. Readers can use their own imagination of what he might look like and his clothing. One might also refer back to the previous article about the look of Andreas’ effects when he died. Center stage on the table would be his book: Wahren Christentum, True Christianity.

As to the two wives which were here in America with Andreas, Maria Magdalena Schmutz and Anna Maria Margaretha Friedler, we can be sure that they were similar in looks and dress to other Pennsylvania Deitsch “Hausfraus.” These matriarchs were in charge of the household and the children, which would include the daily feeding of many mouths, providing respectable clothing, and of all things within the very important kingdom of home at the Hagenbuch homestead.

These grandmothers of many of us might have portraits painted similar to the one of Mrs. Thomas Everette and her children with some additions. Along with the children symbolizing family, wives Magdalena and Margaretha would be sitting at a table with papers of recipes, household accountings, and the Heilige Schrift—the Holy Bible. Also on the table might be tableware, breads, and vegetables. A blazing fireplace could be in the background with cooking utensils and steaming pots. Hanging behind the wives would be sausages and freshly killed game such as rabbits and a turkey. All these items represent care of the family and the difficult, necessary work these wives accomplished daily and throughout their lives.

We must continue this thread and explore the careers and necessary work of the earliest Hagenbuch children. It is another slice in the important genealogical work of our family.

another good article….thanks again

I have listed in a document that heirs of Peter Klingaman-DEC-Date28 Feb 1829.

Marcles-Mary Elizabeth-Klingaman married John Knepper–dec-leaving nine children.

Magdalena Knepper married Jacob Hagenbuch.

Salone Knepper married Isaac Hagenbuch.

Peter his sons were Peter married Barbara Faust, John Married Catherine Hagenbuch, Jacob married Magdalena [Molly] Faust, Christian married Anna Marie

Oswald, Michael married Anna Marie Schmidt. I do not have written proof for his sons.