The Mysterious Religiosity of Andreas Hagenbuch

Ever since I was a young man and first became acquainted with my great great great great great grandfather, Andreas Hagenbuch through the research of William Hagenbaugh in California, I have been extremely curious about him. Over the years more and more has been learned, more stories have come forth, and the curiosity about this man’s personality and beliefs has become stronger. Yes, it does border on obsession and I can even picture what he looked like!

For all those years Andreas’s religious beliefs and practices never were much of an issue with me. He was surely Lutheran as my branch of the family has remained up to the present. Since he came from near the Stuttgart area and his ancestors before him came from north of Zurich, Switzerland, I never wavered in my belief that the Hagenbuchs were Lutheran as far back as the beginning of the Reformation era.

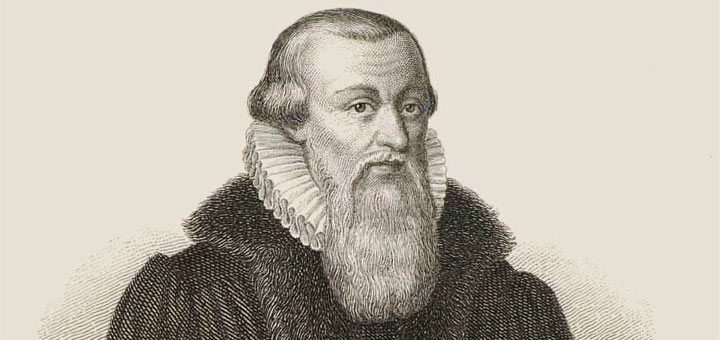

It was quite a revelation to discover that Andreas owned Johann Arndt’s book True Christianity (In German: Wahres Christentum, published between 1605 and 1610) and he willed this to his youngest son, John. It seems that Andreas wasn’t just Lutheran, he was a Lutheran Pietist! A future article will dive into further details of Arndt’s beliefs as written in “the book” (as I now refer to it when discussing religion with my son, Andrew). For this article I want to flesh out how Pietism may have influenced Andreas and subsequently, our unique Hagenbuch genealogy.

I have found, from contacting several historical libraries, that it was not uncommon for 18th century Pennsylvania Germans to own a copy of “the book”. However, it is a very curious act that Andreas willed it to his son John. It proves that Arndt’s Pietist beliefs were extremely important to Andreas. So along with all the other thoughts I have always had about his personality and beliefs, suddenly Andreas wasn’t just another Lutheran immigrant. This raised more questions.

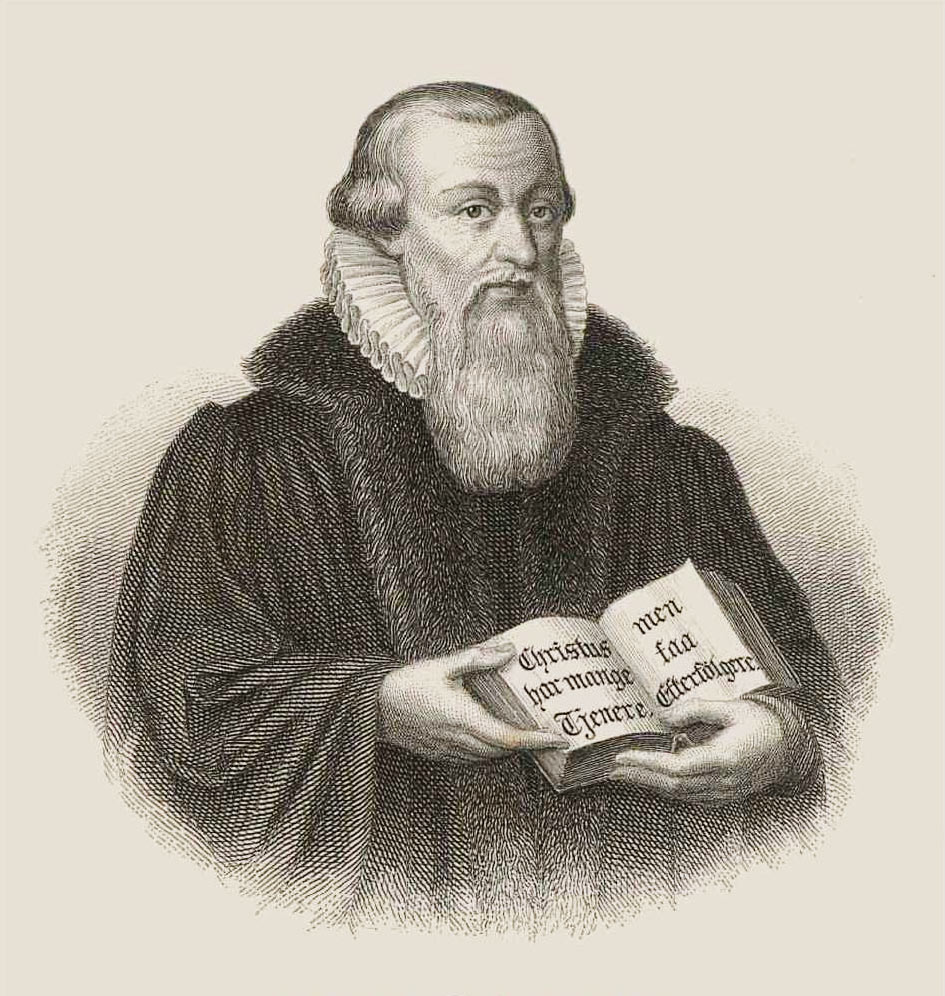

Were Andreas and his family true supporters of the local Lutheran congregations in upper Berks County? Pietism is a strong inner faith that is more concerned with Bible study with family in the home than with the Lutheran service and liturgy in congregations which was promoted by Henry Muhlenberg – the founder of Lutheranism in America.

Was Andreas a Pietist when he came to America in 1737 and did “the book” come with him from his home in Germany? Is there a connection between the German Hagenbuchs and the formulation of the Pietist movement by Phillip Spener in 17th century Germany (Spener, b. 1635 d. 1705, gives credit to Arndt as his mentor)? Did Pietism have a bearing on Andreas’s great grandfather, Hans Jacob Hagenbuch, leaving the area north of Zurich (town of Hagenbuch) in 1652 and moving to north of Stuttgart? What religious beliefs did our Swiss ancestors hold that might have influenced them to leave Switzerland? Did these beliefs carry down three generations to Andreas; those Pietist beliefs coming with him to America and possibly putting him at odds with the mainline Lutheran beliefs of the congregations at New Bethel Church (Rosenthal) and the Jerusalem Red Church?

These questions came to a head in the last few weeks as my wife Linda and I took a 10 day trip in Germany to visit the towns, cities, and sites where Martin Luther lived, preached, and brought about what some religious historians classify as the greatest religious upheaval and change that the world has ever experienced. Although I grew up knowing most of Luther’s history and a few months previous to our recent trip I read several Luther biographies, the tour of Luther sites drove home the great sacrifices that Luther made because of his faith. His strength, courage, and commitment to his mission were unshakeable.

The German government has spent millions of Euros to present Luther’s story and the history of the Reformation by creating new museums and refurbishing old ones. Thousands of Luther artifacts, art, Reformation articles, and signage are now available for the public to learn about this era which did change 16th century Europe and influenced world history. And, to my delight, over and over I found references to the piety of Luther and other reformers.

The word “piety” kept cropping up, with the climax coming on the day that we visited Wartburg Castle. Before arriving at the castle our bus went through the town of Halle, the center of Pietism, where Arndt, Spener, Luther, and even Muhlenberg spent time. At Wartburg Castle, the museum had a small section about Spener and Pietism. More and more I wanted to wrap my genealogical beliefs around the possible relationship of Luther, Pietism, “the book”, and Andreas Hagenbuch.

One must understand that Andrew and I often converse, sometimes daily, about our ancestor research and future articles. Our deepest conversations revolve around the personalities and beliefs of those relatives in the past. What were they really like? What did they think? Why did they make certain decisions? What made them tick?

Upon returning to Pennsylvania on Saturday night, May 20, I was filled with the burning questions about Andreas and his religious beliefs, mainly Pietism. As always, I did some research and then turned to Andrew. We are still trying to get a handle on what was happening in Zurich in the mid-1600s which may have influenced Hans Jacob Hagenbuch (Andreas’s great grandfather) to pick up and move to the Stuttgart area. However, I posed certain questions to Andrew in an email concerning Andreas, Pietism and the book. Here is Andrew’s theory:

Andreas was primarily against authority, which did factor into his beliefs as well. He was an ambitious person too.

According to your records, his father and mother died prior to 1737. When his first wife died in 1736, he has nothing to tie him down. He found a second wife who was less connected to home – maybe someone his parents wouldn’t have approved of? And, in 1737 he finally does something he had been meaning to do for a while. He goes in search of more opportunity. Yes, there may have been a search for freedom here too, but I bet it was freedom from authority – in life, religion, everything.

Andreas associates with Daniel Schumacher, who was also anti-authoritarian. He supports the Revolutionary War and raises his sons to do the same.

He bounces between churches and doesn’t sign his name to the founding of any of them, even though he was there when all these churches were founded. His children are baptized and confirmed by Schumacher, at New Bethel, and at Jerusalem Red Church. In that way, I just feel like he didn’t show strong loyalty to churches. The pietist part he found appealing was home practice and study. Since he could read and write, he worked at home with his family and that tradition carried through to the whole teaching thing with Timothy and Michael. I suspect their education came from learning the Bible, which they studied at home.

I guess I will say this about your question: All of the churches (not just New Bethel) had different beliefs than Andreas, which is why he didn’t show undying support to any of them. Pietism and personal beliefs may have been conviction. But they also could have been part of his desire to remain independent and not invest in any one religious institution.

So, there you have it. Maybe we haven’t made solid headway in fleshing out this very important part of Andreas Hagenbuch’s personality – that part which dealt with his religious beliefs. But it does add another layer to his character, a layer which I have great pride in; and a layer steeped in strong, yet independent Christian beliefs influencing all the other layers of his character.

To conclude, as Andrew and I constantly tell each other, trying to solve one mystery leads to many more; all the more intriguing!

Mark, I was delighted to find you via Patrick Donmoyer. You reviewed his book on PA Dutch Powwowing. I was always told my maternal grandmother Sallie Beer/s, daughter of Rosanna Hagenbuch was a powwow woman.

In researching powwow practices online I found your review and the Hagenbuch newsletters. What a font of knowledge for my research – thank you.

My FIVE GREAT grandfather was also Andreas Hagenbuch. So we must be distant cousins; sixth degree maybe?

My line via Andreas follows: son Heinrich, son John, son Reuben, daughter Rosanna (md Alfred Beer), daughter Sallie Beer/s (md James Redline), daughter Alice Redline (md Robert Tobias). Robert and Alice (dec) are my parents.

I’d love to communicate with you further. I grew up in Berks County and graduated from Reading HS and Kutztown when it was a State Teachers’ College.

I am the genealogist in our family and am pretty convinced we are distant cousins!

Hi Evelyn. Nice to hear from you! I am Mark’s son and site coauthor. Sadly, Dad died earlier this year, but I am happy to connect and I am continuing his genealogy work. You can message me directly through our contact form if you’d like to chat: https://www.hagenbuch.org/contact-us/

We have your family line up through Rosanna (Hagenbuch) Beer in our database: https://beechroots.com/person/2311/rosanna-hagenbuch-beer Thank you for providing the rest of your line.

Yes, we are distant cousins! My line is through Andreas’ son Michael (b. 1746) while, as you know, yours is through his eldest son, Henry (b. 1737). You are right that you are a sixth cousin to my father, Mark, and a sixth cousin once removed to me 🙂