Life as a Lady Physician: Dr. Phoebe H. Flagler Hagenbuch

Prior to the 20th century, it was rare to encounter a female medical doctor. In fact, according to the University of Alabama, only about 5.5% of all American physicians were women in the year 1900. Yet, one of those few was a member of our family—Dr. Phoebe H. (Palmer) Flagler Hagenbuch.

Phoebe Hallock Palmer was born on February 22, 1832 to John and Mary Ann (Bacon) Palmer in Pleasantville, New York. John was a Quaker and worked as a drover, driving herds of livestock from New York to sell in Pennsylvania. During the 1840s, the family relocated to Stroudsburg, Monroe County, PA. Here, Phoebe met John A. Flagler (b. 1823)—another drover and a Quaker. The two were married by 1850 when she was 18.

The couple appear to have had no children of their own. While the 1860 census shows two children living with them, Mary Ann Carner (age 17) and William “Willie” Davis Palmer (age 1), these were the biological children of Phoebe’s siblings, Mary Ann (Palmer) Carner and William E. Bacon Palmer. In 1870 Willie, now 11, was still living with the couple and helping John Flagler with his modest farm. Phoebe remained at home, keeping house. However, she desired something more for her life.

By 1874, Phoebe H. (Palmer) Flagler had enrolled at the Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania and was working towards a degree in medicine. The college was one of only two institutions in the United States where women could train to become medical doctors. To attend school, she left her home in Stroudsburg and boarded in Philadelphia, where the college was located.

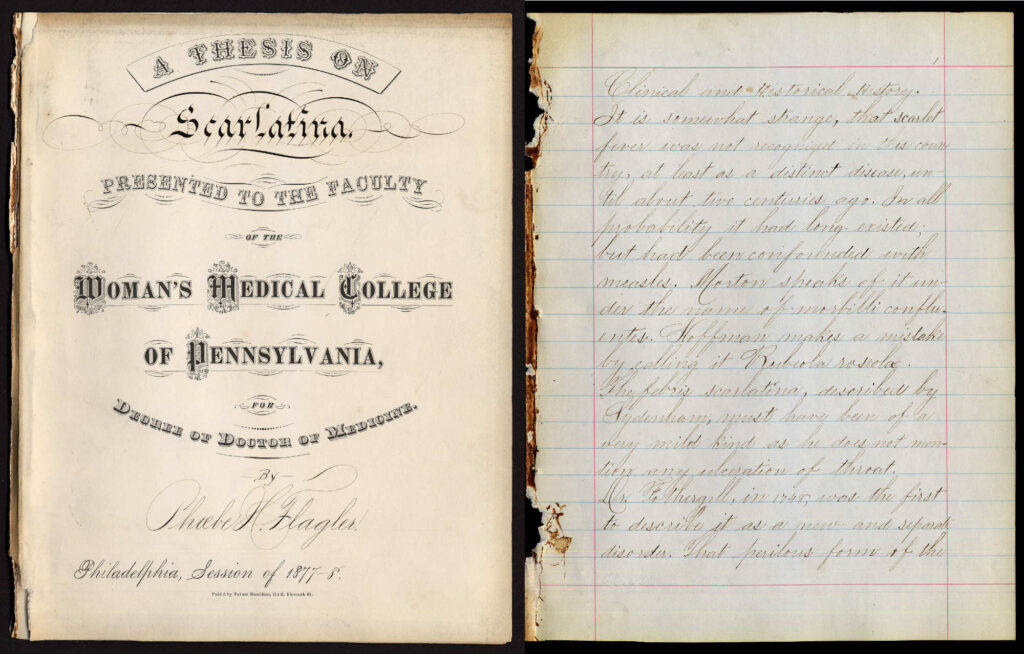

Sadly, John did not live to see his wife graduate. He died suddenly on January 31, 1876. Now a widow, Phoebe continued her studies. From 1877 to 1878 she researched and wrote her doctoral thesis on scarlatina, better known today as scarlet fever. The 37 page thesis was entirely handwritten in cursive and is in the archives at Drexel University College of Medicine, an institution that absorbed the Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania in 2003.

In her thesis, Phoebe examined the causes of and potential treatments for scarlet fever. On one page, she wrote:

There is a tendency among some physicians to attribute many diseases to microscopic spores, fungi, or animalculae. There may be some reason for this [but] it is by no means certain whether they are the cause.

This passage demonstrates her uncertainty towards germ theory. Indeed, it was not until the 1880s that doctors isolated streptococci bacteria and showed these pathogens were present in patients afflicted with scarlet fever. The connection between bacteria and the disease was finally confirmed in the early 1900s. Phoebe’s thesis was accepted, and at the age of 47, she was conferred a Doctor of Medicine degree on March 13, 1879.

Thesis on Scarlatina written by Phoebe H. (Palmer) Flagler Hagenbuch, 1878. Credit: Drexel University Archives

Shortly after graduation, she moved with Willie to the town of Bryan in Williams County, Ohio. There, according to the 1880 census, she began to practice as a physician, while Willie worked as a painter. The two lived with her widowed sister, Catherine (Palmer) Mitchell, and her children.

Around 1885, Phoebe remarried, this time to George Miller Hagenbuch (b. 1826) of Williamsport, PA. George was a widower who ran a drugstore in that city. His first wife, Campaspa Mellick had died in 1876. George has been previously featured in an article series about a medicine bottle that was sold at his store. His line is Andreas (b. 1715) > John (b. 1763) > Simon (b. 1788) > George Miller (b. 1826).

Dr. Phoebe H. Flagler Hagenbuch, as she wrote her name, relocated to Williamsport and set up her practice in a building at the corner of Park Avenue and Hepburn Street. A few years later, she moved her office downtown to 435 Market Street. She saw patients at this location until the mid-1890s, when she and George separated.

Phoebe returned to Stroudsburg, PA and opened an office at the corner of Sarah Street and North Eighth Street. In 1900, she officially divorced George M. Hagenbuch on the grounds of “not supporting her, forcing her to live with his daughters, and [giving her] menial chores.” She had been a housewife once before and, at the age of 68, had no interest in returning to that life.

She decided to keep the Hagenbuch family name and continued to practice medicine as Dr. Phoebe H. Flagler Hagenbuch. While some female doctors were considered second rate to their male counterparts, Phoebe did more than prescribe pills to her numerous patients—men, women, and children. In the book, Send Us a Lady Physician: Women Doctors in America, 1835–1920, William Hoffman describes how his grandmother, Phoebe, also performed surgeries:

I have heard stories of table top operations. . . . One man in the neighborhood . . . had his arm amputated under these conditions by her. He had gotten it caught in a corn shucker.

The 1900 census shows Phoebe living in the house next to Willie, who was now married. He and his wife, Jennie, had two children: Ethel and Olivette. It should be noted that Willie was recorded as “William D. Flagler” rather than “William D. Palmer.” By the 1910 census Phoebe, still working as a physician, had moved into Willie’s home. She was listed as his mother, though he was using the last name “Palmer.” On the 1920 census, Phoebe, now 86 years old, was retired and still living with Willie’s family. Dr. Phoebe H. (Palmer) Flagler Hagenbuch died on November 22, 1927 at the age of 95. She was buried at the Stroudsburg Quaker Cemetery.

Did John and Phoebe (Palmer) Flagler adopt their nephew, Willie, as their son? The death certificate for William “Willie” Davis Palmer clearly notes that his biological parents were William E. B. Palmer and Harriet Clark. Harriet died in 1859, the year after he was born, and he spent most of his life with Phoebe. Even if he was not legally adopted, he seems to have thought of her as his mother.

Pocket surgical kit once owned by Dr. Phoebe H. (Palmer) Flagler Hagenbuch. It was donated by the Hoffman family to the Monroe County Historical Society. The spatula-like implement near the bottom is a grooved director and tongue tie, used when performing a lingual frenectomy (cutting a tongue-tie).

This then helps to explain William Hoffman’s comment about his “grandmother” Phoebe. Research shows that William L. Hoffman (b. 1914, d. 1992) was the son of Oram P. and Olivette A. (Palmer) Hoffman. Olivette (b. 1889), as mentioned earlier, was the daughter of William “Willie” and Jennie (Peltier) Palmer. In other words, Phoebe was actually William Hoffman’s adopted great grandmother or, biologically, his great great aunt.

The life of Dr. Phoebe H. (Palmer) Flagler Hagenbuch ushered in a new era in medicine, one where women could participate equally alongside men. Today, over 50% of the doctors under the age of 45 are women. Her story also demonstrates how one’s determination can lead to a successful and meaningful career, even later in life.

Each year during Women’s History Month, the Monroe County Historical Society celebrates Phoebe as a notable lady and the first female physician in the county. Though a Palmer by birth and a Flagler by her first marriage, Phoebe’s second marriage to George M. Hagenbuch connects her to our family tree and permits us to remember her as an accomplished Hagenbuch relative.