John Hagenbuch: Runaway Apprentice Becomes Prosperous Farmer

John Hagenbuch was the youngest child of Andreas and Maria Margaretha Hagenbuch. He was born on October 4, 1763 and baptized on the 16th at New Bethel Church in Albany Township, Berks County, Pennsylvania. At the time of John’s birth, Andreas was 52 years old and a grandfather.

When Andreas died in 1785, he left his youngest son, John, a curious gift–a copy of the book Wahres Christentum (English translation: True Christianity). The book and its contents were discussed in a previous article. None of Andreas’s other children were willed books, leading one to wonder: Why was John given this gift?

A recent discovery in The Pennsylvania Gazette has shed new light onto this mystery:

TWELVE DOLLARS Reward:

Ran away, last night, from the subscriber, a servant man named John Hagenbook [Hagenbuch], a German, a taylor by trade; he is 21 years of age, 5 feet 5 inches high, fresh coloured, much pitted with the small pox, and has black hair which he wears cued; had on an orange coloured coat of fine cloth, a clouded knit jacket, nankeen breeches, new fine shirt, white cotton stockings, good calf-skin shoes, plated shoe and knee buckles, and a castor hat. Whoever takes up and secures said servant in any goal, or delivers him to the subscriber, shall have the above reward, and reasonable charges, paid by ANDREW HERTZOG;

N.B. A certain Henry Voelker went off with the above servant; he is a free man, a taylor by trade, and persuaded the servant to go with him.

August 22, 1785

The aforementioned runaway is almost certainly Andreas’s son, John. While Andreas’s eldest son, Henry, also had a son named John, he was born August 4, 1762 and would have been 23 at the time the above was written.

The advertisement is a treasure trove of information about John Hagenbuch. Most notably, he was apprenticed as a tailor to Andrew Hertzog, who is offering the $12 reward (around $300 when adjusted for inflation). Records do indeed show a tailor, Johann Andreas Hertzog (b. 1730, d. 1810), who lived in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania during this time.

As the youngest of Andreas’s sons, John would have had little hope of acquiring the family homestead and the livelihood it provided. Property deeds reveal that Andreas signed over the majority of his estate to his sons Michael and Christian in 1782. With little future at home, apprenticing to learn a trade would have been a reasonable career choice for John.

Philadelphia is about 75 miles away from the Hagenbuch homestead, a substantial distance in those days. However, the Hagenbuchs were familiar with the city as well as the textiles industry. As noted in Andreas’s will, the family was producing significant quantities of linen fabric which would have been sold to tailors. Andreas may have personally known Hertzog from business dealings and helped his son to gain a tailor’s apprenticeship.

Apprenticeships typically lasted four to seven years and were set up as a contract between a master craftsman and the apprentice. Contracts for younger apprentices were often cosigned by parents. Along with learning the tailor’s trade, John likely received food, lodging, and clothes. In exchange, he would have been required to serve his master without pay until a set termination date, perhaps until his 25th birthday. His contract may have also restricted him from marrying and gambling.

Leaving an apprenticeship early was a serious breach of contract and appears to have occurred with some regularity in colonial America. Parents, when cosigners of an apprentice’s contract, were often held financially responsible for early termination. Unfortunately, without a copy of John’s contract, it’s impossible to know the full details of the arrangement, leaving more questions than answers.

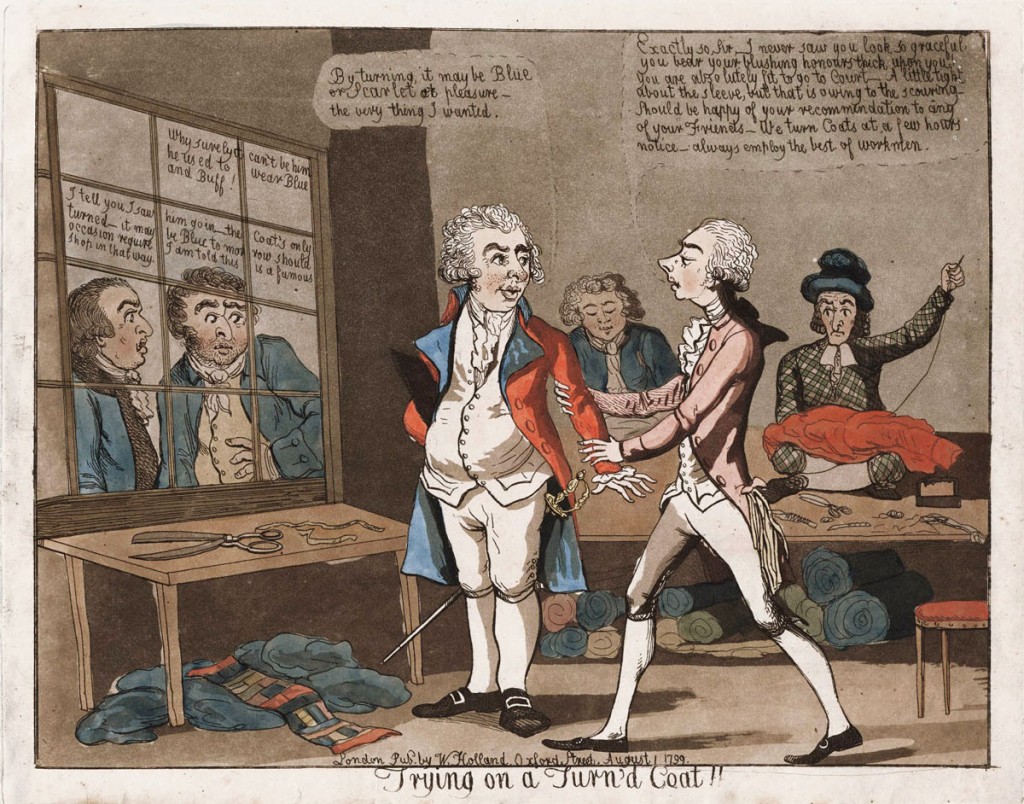

Besides the apprenticeship, the advertisement provides a detailed physical description of John. He was about five and a half feet tall with a youthful face that was scarred from small pox. He wore his hair in a queue at the back. John also appears to have been something of a dandy and was exceptionally well dressed for a 21 year old man from rural Pennsylvania. One has to wonder: Did he buy these clothes himself or were they provided by his master?

When he escaped, John was wearing an orange coat over a clouded (yarn that was not solid in color) knit waistcoat with long sleeves. He wore a fine shirt, white cotton stockings, calf skin shoes with silver buckles, Nankeen breeches also with silver buckles, and a castor hat. All of his clothing points to the elegance of a Philadelphia gentlemen.

Orange velvet coat, waistcoat, and breeches, 1775-1790. Credit: mfa.org/The Elizabeth Day McCormick Collection

As was mentioned in a previous article, linen was an everyday fabric in the 18th century colonies, while cotton was more of a luxury item. Some of the finest cotton was that from Nanjing, China. Having a natural light yellow color, Nankeen cotton breeches and later trousers were fashionable in early America.

In addition, John is also noted as wearing a castor hat–one made of beaver fur. This was probably a tricorn hat. A beaver hat, like Nankeen breeches, was a fashionable item and would have been more expensive than a common, wool felt hat.

Finally, it is worth pointing out that John’s knee length breeches had silver buckles on them. Breeches were commonly made with buttons and a fabric tie at each knee. The ties could be tightened to help hold the stockings in place. Fashionable men, however, were able to afford buckles for each knee instead of ties.

Compared to his father, who dressed in the deerskin breeches of a frontier farmer, John must have appeared a cosmopolitan, urban dandy. This contrast may demonstrate a point of contention between father and son. John’s lifestyle and quite possibly his values appear at odds with the ones he had been raised with.

As was touched upon previously, Andreas Hagenbuch owned a copy of Johann Arndt’s book, True Christianity. This book is mentioned both in his will from 1785 and in a document from 1782 where he sold most of his estate to his sons, Michael and Christian. One item he did not sell was True Christianity. It is mentioned by name as one item Andreas wanted to keep, underscoring the value it held in his life.

Andreas was almost certainly a Godly man who believed in Arndt’s teachings of living one’s life through Christ. Though pure speculation, it is easy to see how John’s urban, worldly life could have been a source of concern for his aged, devout father. This is even more fascinating to consider knowing that in his will Andreas specifically gave Arndt’s book, one of his most valued personal possessions, to John.

John was likely in Philadelphia when his father died sometime late in the summer of 1785. The timing of the son’s escape appears more than coincidental. One can only wonder if, upon hearing of his father’s death, John ran away from Hertzog on August 22, 1785 and broke his apprenticeship contract. While the advertisement in The Pennsylvania Gazette pins the motive on Henry Voelker, who supposedly persuaded him to run away, there is likely more to the story.

It is known that Andreas’s death presented John with a windfall of 150 pounds (around $30,000 today). Additionally, if Andreas had cosigned the contract with Hertzog, John may have realized that his father’s death meant fewer financial repercussions for leaving the apprenticeship. In either case, John probably saw an opportunity and took it.

Records support the notion that John left Philadelphia and returned to the Hagenbuch homestead that summer. He is listed as a single man living in Albany Township, Berks County, Pennsylvania on the 1785 tax assessment list. By all accounts, Andreas’s death marked a turning point in John Hagenbuch’s life. He left his previous life behind and became a prosperous farmer, not unlike his father.

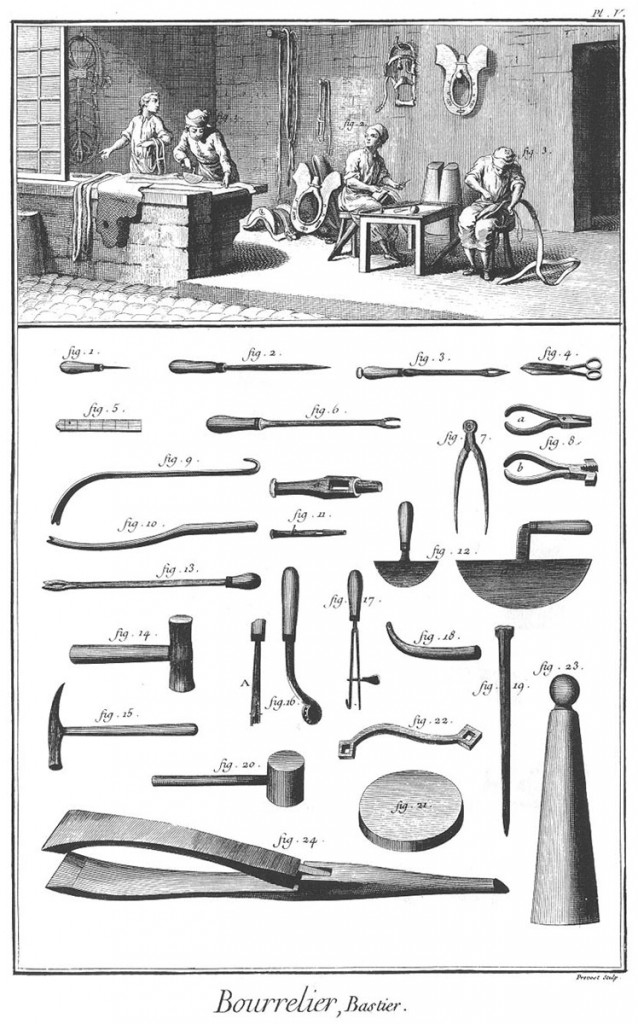

Harness and saddle maker workshop and tools. Diderot, 1763. Credit: The Encyclopedia of Diderot & d’Alembert Collaborative Translation Project

After returning to the family homestead, John eventually moved to be closer to his older brothers Christian and Henry in Allen Township, Northampton County, PA. On the 1788 federal tax list he is listed as a saddler, a profession which would have used some of his skills learned as a tailor. Previous to this in 1787, he married Maria Magdalena Dreisbach (b. Sept. 9, 1766; d. Jan. 3, 1825). She was the first cousin of Susanna “Dreisbach” Hagenbuch, who was married to John’s brother, Christian.

Magdalena also happened to be the daughter of Simon Dreisbach, Jr. (b. 1730, d. 1806) and Dorothea Teas (b. 1732, d. 1773). Simon was a delegate to the Pennsylvania State Convention in 1776 and signed the Pennsylvania State Constitution. He may also have contributed to the effort to move the Liberty Bell from Philadelphia to Allentown for safekeeping during the Revolutionary War.

Together, John and Magdalena Hagenbuch started a family near Kreidersville, PA. Their children included: Simon (b, July 4, 1788; d. Sept. 10 1858; m. Elizabeth Miller in 1808), Johann Conrad (b. Aug. 15, 1790; d. Jan. 23, 1865; m. Mary Ruckle), John Jr. (b. Oct. 5, 1791; d. 1861; m. Christina Hess), Jacob (b. Oct. 11, 1792; d. May 31, 1861; m. Abilona Hayman), Michael (b. Aug. 18/19, 1799; d. Apr. 12, 1852; m. Mary Hess), Daniel (b. May 13, 1803; d. April 6, 1878; m. Elizabeth Hill), Jonas (b. Nov. 23, 1810; d. May 26, 1847; m. Elizabeth Heffner), and Charles (b. Jun 6, 1811; d. Mar. 26, 1870; m. Elizabeth Hess).

John Hagenbuch is buried at Hidlay Church cemetery in Centre Township, Columbia County, Pennsylvania

In 1806, perhaps using money left to them in Simon Dreisbach’s will, the family relocated to a large, 500 acre farm in North Centre Township, Columbia County, Pennsylvania near present day Hidlay Church. It was not by chance, though, that they had chosen this location. Henry and Andrew Hagenbuch, John’s nephews through his brother Michael, had already established themselves in this area in 1802. John died March 20, 1846 and was buried alongside his wife at Hidlay Church.

History is often incomplete, leading to guesswork and supposition in order to fill in the blanks. Was John Hagenbuch a fashionable, careless dandy in his youth? Was he Andreas’s prodigal son and a source of worry for his aging father? What did it mean that Andreas willed John his valued book, True Christianity?

It is exactly these mysteries which make researching one’s family history so enticing. Whatever may have happened when he was young, John Hagenbuch went on to lead a prosperous and productive life. He also left many descendants, some of whom are likely reading this site today.

What set him on that path? Was it age and maturity? Was it his wife and the respectable family he married into? Or was it, just maybe, the book he had been given by his father?

The interpretation of the facts is ultimately left to the reader.