John D. Hagenbuch Testifies Before Congress and Meets Samuel Gompers

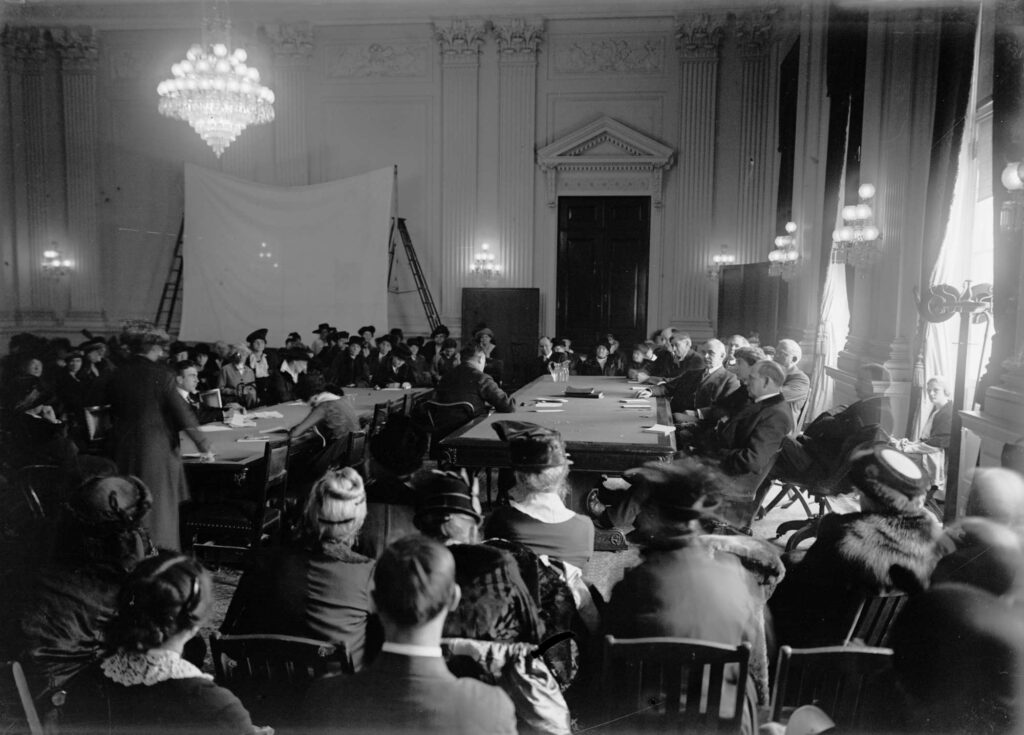

On Tuesday, June 24, 1902, twenty-eight-year-old John D. Hagenbuch (b. 1874) sat before the United States Senate Committee on Education and Labor in Washington, D.C. A series of hearings had been convened to listen to testimony related to a bill that, if passed, would limit the number of hours laborers in private businesses could spend each day completing work for the United States government. It was an early step towards implementing an eight-hour day, though it does not appear to have passed in 1902.

Four senators were present at the hearing, including Moses E. Clapp from Minnesota who served as acting chairman of the committee. Also there were Joseph K. McCammon, a lawyer and former military judge who represented businesses such as the Bethlehem Steel Company, and Samuel E. Gompers, president of the American Federation of Labor who spoke on behalf of workers.

At 10AM the proceeding began and the following was recorded:

Senator Clapp: Will you state your name, Mr. Hagenbuch?

Mr. Hagenbuch: My name is John D. Hagenbuch.

Senator Clapp: And your occupation?

Mr. Hagenbuch: My occupation is that of stenographer and typewriter for the Bethlehem Steel Company.

Senator Clap then permitted Mr. McCammon to question the witness on behalf of his business clients:

Mr. McCammon: Whose stenographer are you?

Mr. Hagenbuch: I am the stenographer for Mr. McIlvain, the president [of Bethlehem Steel].

Mr. McCammon: Were you present at the meeting of workmen in South Bethlehem—

Mr. Hagenbuch: I was not present at that meeting.

Mr. McCammon: Excuse me. Wait until I get through. I refer to the meeting on the evening of March 14, which was addressed by Mr. Gompers.

Mr. Hagenbuch: I was not present at that meeting.

Mr. McCammon: That is all, Mr. Chairman.

To understand McCammon’s line of questioning and the reason for Hagenbuch’s testimony, one must return to a previous meeting of the Senate Committee on Education and Labor held on June 17, 1902. During the proceeding, Thomas H. Flynn, a paid organizer for the American Federation of Labor, testified that 37 men had been fired from the Bethlehem Steel Company after attending a large, workers’ rally on the evening of March 14, 1902 in South Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. The featured speaker at the gathering was Samuel Gompers and, by the end of the night, several hundred workers had unanimously adopted a resolution supporting federal legislation for an eight-hour workday.

At the June 17th hearing, Gompers testified that while he was at the rally someone pulled him aside and pointed to a man in the audience with unusual behavior. The man was a stenographer, and he appeared to be recording the names of workers in attendance, presumably so they could be dismissed by Bethlehem Steel Company which was against organized labor. Gompers tasked Flynn with investigating the incident and interviewing the men who had been fired. One identified the stenographer at the rally as John D. Hagenbuch. However, McCammon’s questioning and Hagenbuch’s testimony suggested that was incorrect.

Senator Clapp asked for clarification:

Senator Clapp: Were you present at any meeting about that time?

Mr. Hagenbuch: On the morning of March 14, the day of this meeting referred to, Mr. Gompers addressed the students of Lehigh University on the subject of “Labor’s Struggles and Aspirations.” We received a printed card, which is sent to everybody, announcing among a number of lectures this particular one of Mr. Gompers. The matter was drawn to the attention of President McIlvain by his secretary, and at the president’s request, I went there and took notes of that lecture. I have with me both the original notes and the transcript into English.

Senator Clap: You say that was in the forenoon?

Mr. Hagenbuch: That was in the morning at 11:30.

. . .

Senator Clapp: Were there any of the employees of the company [Bethlehem Steel] there?

Mr. Hagenbuch: I saw no one there whom I knew; neither had I received any instructions of any sort to see whether anyone of our company did attend. I went entirely uninstructed, for the purpose of making a transcript of the lecture.

Senator Clapp: Do you know anything about a meeting that was held that evening [the workers’ meeting]?

Mr. Hagenbuch: I knew of it through the newspapers.

Senator Clapp: Do you know where it was held?

Mr. Hagenbuch: It was held in the municipal hall of South Bethlehem. Mr. McIlvain was asked whether he cared to have me report to that meeting. I asked him that question. He said, that inasmuch as it was on the question of the Chinese Exclusion Act, he did not see that matter would be of any interest to them, and I was not present.

Senator Clapp: Do you know whether there was any stenographer there or not?

Mr. Hagenbuch: No, sir; there was no stenographer there.

Senator Clapp: You do not know that, do you?

Mr. Hagenbuch: To the best of my knowledge and belief. All questions are answered with that reservation.

At this point, Senator Clapp turned to Samuel Gompers. Gompers was an important figure in the fight for workers’ rights around the turn of the 20th century. Born in Britain in 1850, he immigrated to the United States with his Jewish parents when he was thirteen. In 1886, Gompers founded the American Federation of Labor (AFL), a national organization of labor unions. As its president, he advocated for higher wages and shorter working hours. He was against socialism and unrestricted immigration to the United States, explaining his interest in the Chinese Exclusion Act which prohibited laborers from China from entering the country.

Samuel Gompers continued the questioning:

Mr. Gompers: You say that at the request of Mr. McIlvain, the president of the Bethlehem Iron Company, you attended the lecture at Lehigh University Hall on the morning of March 14?

Mr. Hagenbuch: Yes, sir.

Mr. Gompers: Did you take stenographic notes of my address?

Mr. Hagenbuch: Yes, sir.

Mr. Gompers: Are you in the habit of reporting the lectures that are delivered at Lehigh University?

Mr. Hagenbuch: That is the first lecture of that sort which I reported. I may say, however, that several days ago I reported the proceedings of the Alumni Association at Lehigh University.

. . .

Mr. Gompers: But you did not report any of the other lectures besides mine?

Mr. Hagenbuch: None of the other lectures but yours.

Mr. McCammon [interjecting]: Probably none of them were worth reporting except yours.

Mr. Gompers [to McCammon]: The Judge is always complimentary.

Mr. Gompers [to Hagenbuch]: You say you were not at the meeting on the evening of March 14, at Market Hall, Bethlehem, when Mr. Garland and I made addresses on the subject of immigration and the eight-hour question?

Mr. Hagenbuch: I was not present at that meeting, for the reasons previously stated.

Samuel Gompers concluded by telling the Senate committee that he believed John D. Hagenbuch was being truthful in his testimony. While Gompers recognized Hagenbuch’s face, he believed this was because Hagenbuch attended the lecture at Lehigh University, not the workers’ meeting. After answering a few more questions for Clapp and Gompers, Hagenbuch was dismissed, and he returned to his home and birthplace of Pennsylvania.

Born on January 24, 1874, John Daniel Hagenbuch was the youngest son of Jacob (b. 1830) and Elizabeth (Loehr) Hagenbuch (b. 1831). His line is: Andreas (b. 1715) > Henry (b. 1737) > Jacob (b. 1765) > Daniel (b. 1803) > Jacob (b. 1830) > John Daniel (b. 1874). By the age of 20, he was working as a stenographer for the superintendent of the Lehigh Valley Railroad.

In 1894, he married Kathryn E. Blackwood (b. 1876), and the couple had four children together: Jacob (b. 1895), Anna Lovenia (b. 1897), James Blackwood (b. 1899), and Maydell (b. 1902). Around 1900, John was employed by the Bethlehem Steel Company as a stenographer and typist for the president, Edward M. McIlvain. In 1908, he served as the assistant to general manager, Eugene G. Grace, and after that, the assistant to the new president, Charles M. Schwab. Schwab, in particular, actively fought to keep unions and organized labor out of Bethlehem Steel.

Children of John D. and Kathryn (Blackwood) Hagenbuch in 1912 (Left to Right): Jacob, Anna, James, and Maydell

At the age of 40, John was stricken by a sudden paralysis that forced him to retire in 1914. He died two years later on October 18, 1916 and is buried at Nisky Hill Cemetery in Bethlehem, PA. Two of his former bosses, Grace and Schwab, served as pallbearers at his funeral, indicating the strong relationship he had with both men. John has numerous ancestors alive today, several of which read this site.

Our Hagenbuch family has participated in key moments of United States history, a fact exemplified by John D. Hagenbuch’s testimony before Congress in 1902. Not only did he work for one of the most important companies of the early 20th century, Bethlehem Steel, he also interacted with notable personalities such as Samuel Gompers and played a minor role during the hearings that created legislation in support of American labor.