Interpreting Documents: Michael Hagenbuch’s Inventory

One of the joys and sometimes the frustration of genealogy is interpreting historic documents. Wills, inventories, letters, and deeds present opportunities to better understand the past. Of course, this is only possible if we are actually able to read them!

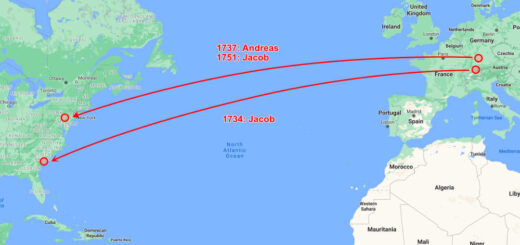

When we feature family documents on this site, we usually present them typed and formatted, making them easier for everyone to enjoy. However, behind each article is a substantial amount of unseen work. Today, we will pull back the curtain on this process and give a few examples of the effort that went into the interpretation of the inventory found within Michael Hagenbuch’s (b. 1746, d. 1809) estate.

On the face of it, Michael’s inventory appears easy to read. It is written in English, not Deitsch, after all. Yet, even documents in English may pose substantial challenges. For instance, this document is a digital scan of microfilm which is itself a photographic copy of ink on paper. With each iteration, some details are lost. Lines where the ink was light or faded may be entirely missing from a scan, making it easy to confuse letters.

Thankfully, modern software applications help to recover some of the details lost to the human eye. Images can be sharpened and the brightness or contrast adjusted. All of these techniques make it easier to interpret what has been written.

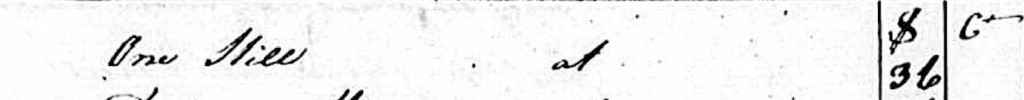

Reading historic documents is further complicated by the style of writing used hundreds of years ago as well as the unique characteristics of the author’s hand. For example, when reviewing the first item on Michael’s inventory, I believed that it said “One Mill” and the middle part of the M was simply faded.

Here is where viewing other instances of a person’s writing can be useful. Further down the word Screw was clearly visible. After comparing its S to the first letter in the supposed Mill, I realized that I had it wrong. The Mill was actually a Still. The next few items on the inventory (barrels of whiskey) provided additional context and supported that, indeed, Michael had owned two stills for the production of spirits.

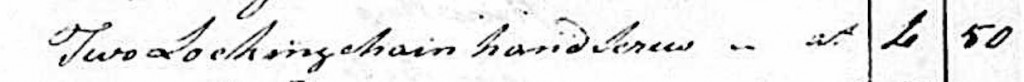

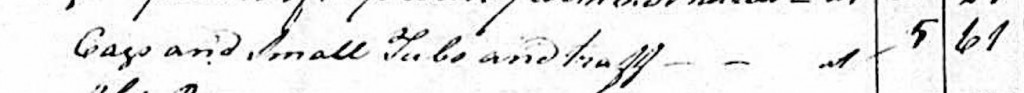

Cags was another confusing word which appears several times on the inventory, usually alongside mentions of tubs and bottles. Initially my father, Mark, and I suspected this was a misspelling of cages. These could have been used to hold chickens or other small animals. However, I kept wondering–what do these have to do with bottles?

It was my wife, Sara, who ended up providing an answer. Whoever wrote the inventory frequently spelled words phonetically. With this in mind, one can imagine a man with a heavy Deitsch accent saying the word kegs with an a sound. Realizing that the Hagenbuchs were distilling, kegs makes sense and fits perfectly with tubs, bottles, and troughs (which were misspelled as traffs).

Sometimes my interpretations of Michael Hagenbuch’s inventory led to humorous results. When I first read the above line item, I couldn’t make heads or tails of it. I ended up translating it as “six bushels of bats.” One can only imagine Michael collecting these winged creatures from his barn and placing them neatly in baskets for storage! Of course, I had it wrong. When my father looked at this line, he quickly replied “Oats! Six bushels of oats.” Having multiple sets of eyes can be extremely useful when reading documents.

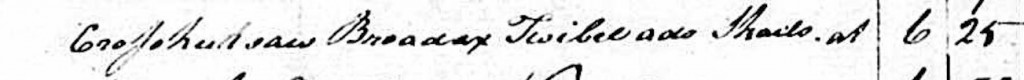

There were a few items within the inventory that used archaic words which are rarely heard anymore. Take, for instance, the above line. It describes a “Crosscut saw, broad ax, twibel ax, shails.” Crosscut saws and broad axes are still known today. However, the twibel ax (spelled as twybil or twibil) is hardly mentioned in the modern world. Upon further investigation, it appears the twibil ax was used to chop mortises from green wood when framing a structure.

The previous line item includes another mystery in the use of the word shails. It almost certainly refers to some type of tool. Currently our best guess is that it might actually be scales or sails. What do you think?

Another archaic word, gammon, is seen a bit later in the document. The definition of this was relatively easy to find. A gammon is a cured hind leg of pork. It was likely preserved through brining or salting and was not fully cooked or smoked like a modern ham.

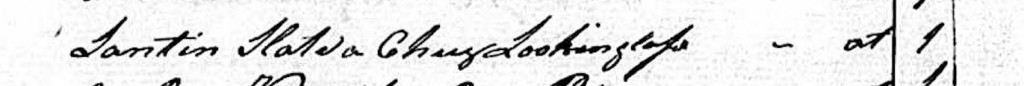

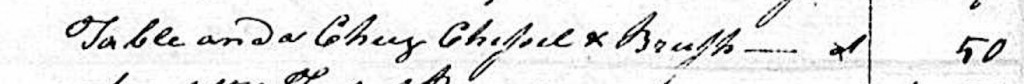

Language and grammar have changed in the last several centuries, as exhibited by the use of the letter s. Older documents make use of the long s character which appears something like a lowercase f. For example, the word brush appears as brufh and glass is written glafs. These types of idiosyncrasies can throw one for a loop.

One of the still outstanding mysteries of Michael Hagenbuch’s inventory is the word chug (or possibly chuz). This is found in two places. First, it is mentioned in the line “lantern slate and chug looking glass.” Second, it is used in “table and a chug chisel and brush.”

What could chug or chuz be referring to? Context clues show it is describing a looking glass (another name for a mirror) and a chisel for working with wood. Initially, I believed chug was a misspelling of cog and was being used to describe something circular. However, now I am not so sure.

Additional research into chisels reveals that it may be the name for a certain pattern or design of the chisel’s cut. This would certainly explain it being used to reference the chisel. Mirrors usually had frames around them, and a wooden frame would likely have been beveled with a chisel.

Interpreting historical documents is rarely a clear and simple task. Of course, this is what makes it fun as well as a bit frustrating. What do you think? Did we get it right with cags as kegs? Could shails actually be scales or have you ever seen a chug chisel? Let us know your thoughts!

The “twibil ads” undoubtedly refers to the two-bladed framing adze used to chop the mortices through 6 to 8-inch thick beams prepared to receive tenons, the ancient joining technique for heavy oak framing. The joint is secured with square oak pegs, driven through round bored holes (the proverbial square peg in a round hole); this process shears off the square corners of the peg and provides a very tight and secure fit. A Westphalian legend tells that the devil once visited a construction site and, being curious, picked up a twibil. Preparing to chop with the tool, he swung it up and cut his forehead with the vertical blade. Realizing his mistake, he turned the axe around and promptly cut a horizontal slice across the vertical one. Having marked his forehead with the cross of Jesus, he threw down the axe and left the job site for good.

I’ll guess the next item is “Skails”, meaning scales for weighing.

A lively imagination is required to interpret the handwriting and spelling of men whose daily language is probably Deitsch!

Forgot to offer my guess at the etymology of the twybil: twy or twi is Low German or Anglo-Saxon for Hochdeutsch “zwei”, meaning two, as in twilight, twin.

The “bil” is likely Hochdeutsch “Beil”, meaning hatchet, as in billhook.