Homestead Economics: Leather Tanning

Life at the Hagenbuch Homestead stank—quite literally!

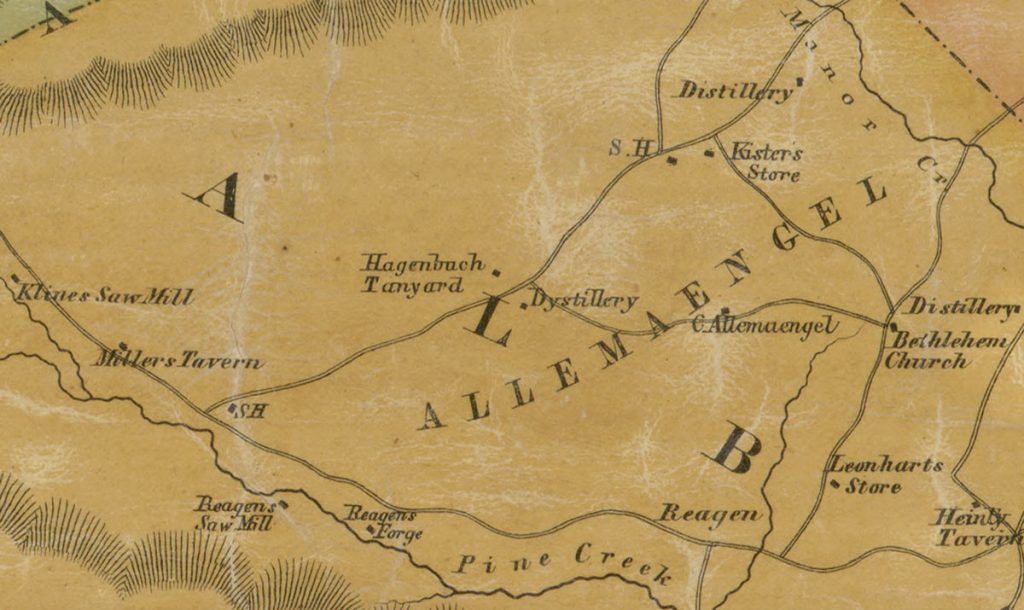

By the early 1800s, the homestead had a sizable tannery, large enough to be recorded on at least one map of the area as the “Hagenbuch Tanyard.” Records also show that several generations of Hagenbuchs participated in leather tanning there.

Leather was an important commodity in the 18th and 19th centuries. It was readily available, versatile, and had all sorts of applications. The military used leather to make horse tack, pouches, ties, straps, boots, carriages, coaches, sheaths, and gloves. Civilians needed it for breeches, pants, aprons, vests, capes, coats, hats, bags, satchels, shoes, and belts. Still other uses for the material included drinking tankards, harnesses, saddles, book covers, hinges, chair seats, and trunks.

Yet, the process of tanning animal hides to produce leather stinks. Along with requiring hard, manual labor, it generates rotting waste, putrid runoff, and noxious odors. For this reason, tanneries were often located outside of towns and away from populated areas.

The first indication that the Hagenbuchs were involved with tanning hides appears in my father’s, Mark Hagenbuch’s, oral history of the family. According to a story he remembers, Andreas Hagenbuch (b. 1715)—the founder of the Hagenbuch Homestead—was one of the first settlers in Albany Township, Berks County, Pennsylvania to learn the process of brain tanning from the local Lenape. Brain tanning softens a hide using a solution of animal brains.

Historic records that mention Andreas usually describe him as a farmer or yeoman. In fact, the only evidence connecting him to tanning comes from his 1785 estate inventory and notes that he owned “two pair of deerskin breeches.” Nevertheless, it is likely that Andreas had a small tanning operation at the homestead.

Colonial farms produced animal hides every time livestock were slaughtered. The hides were dried and brought to a tannery for processing into leather. In one type of arrangement, the tanner and the farmer would each get half of the finished hide. Although no money was exchanged, the tanner could sell his portion of the hide for cash.

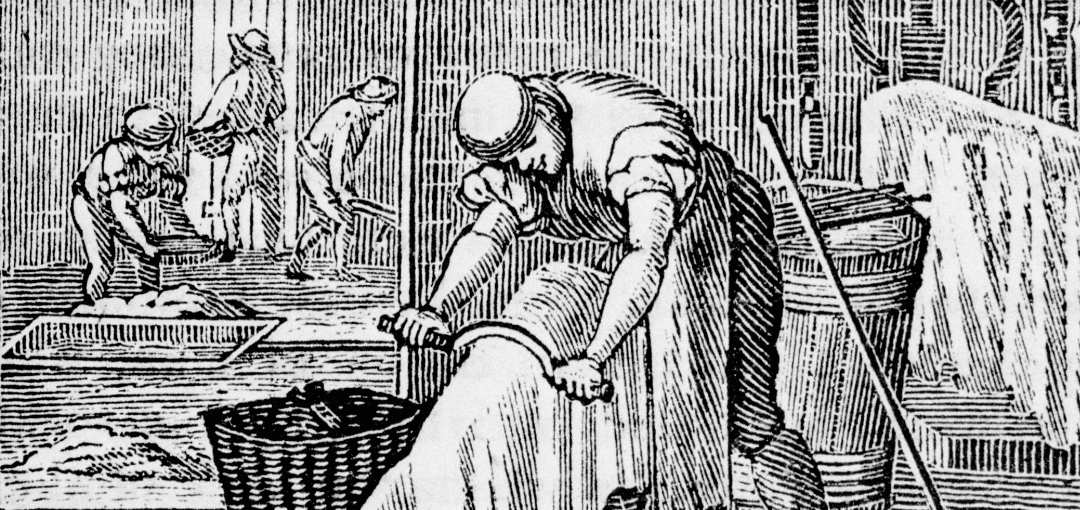

Lithograph “Tanner and Currier” depicting a tannery from 1790. Credit: Library Company of Philadelphia

The Hagenbuchs’ tannery may have begun in the mid-1700s with Andreas tanning his own hides. The resulting leather would have been used by the family for a variety of items, such as Andreas’ deerskin breeches. Eventually, his son Michael (b. 1746) learned tanning and was given charge of the operation. According to Michael’s grandson, Enoch Hagenbuch (b. 1814), his grandfather “was a tanner by trade.”

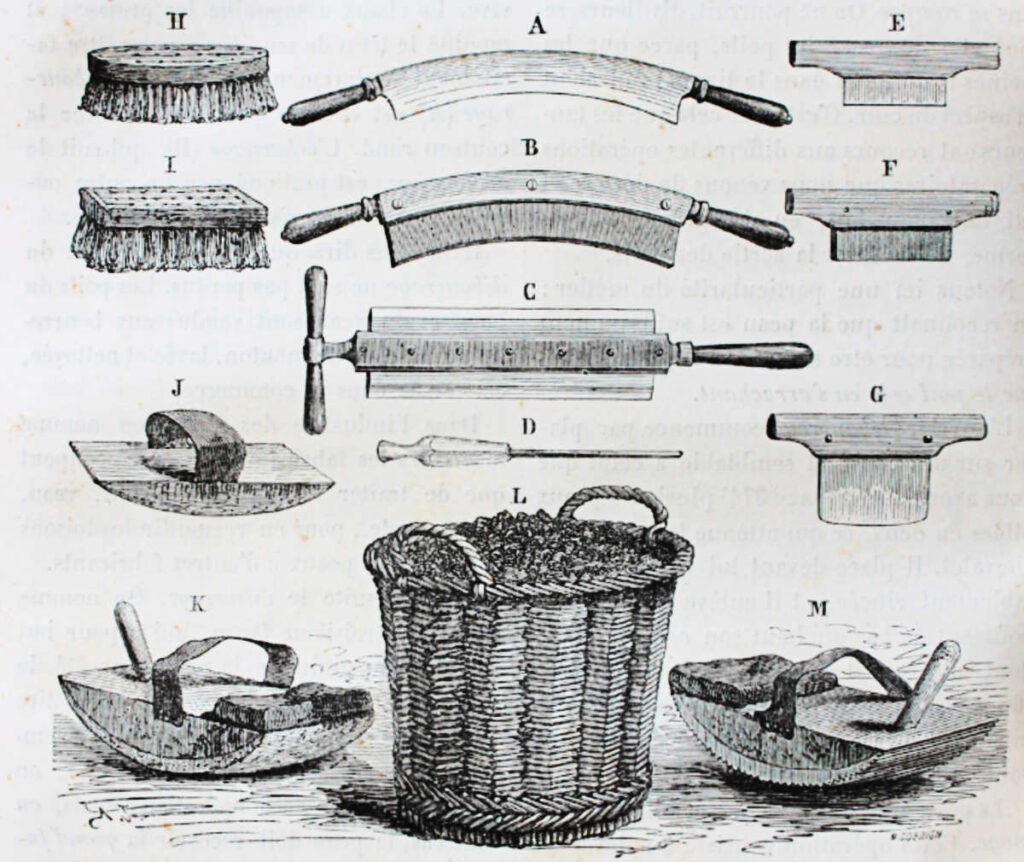

This characterization of Michael is supported by the following items found on his 1809 estate inventory:

- tools for a tanner

- a draw knife

- one shaving horse

- shaving knife

- seven shaving knives and shimmer

- five currying knives and sundries

- 25 pounds of tallow

- twelve hides

- Spanish hides

- leather

The above lists a number of tools used by a tanner such as knives and a shaving horse, as well as hides for working, tallow for making leather pliable, and finished leather. In addition, during the late 1800s Michael purchased 56 acres of mountain land not far from the homestead. While unsuitable for farming, the land was rich in trees whose bark could be stripped, boiled, and used to tan hides, through a process known as vegetable tanning. Watch the below video to see a brief overview of vegetable tanning.

Producing leather through vegetable tanning consists of the following steps:

- Skinning—Animals such as cows, calves, hogs, sheep, and deer are slaughtered. The animal is skinned and the hide removed.

- Curing—To stabilize the hide and prevent putrefaction, it is salted and dried. Cured hides can be transported and shipped for later processing.

- Soaking—The cured hide is soaked in fresh water to remove the salt and make it pliable again.

- Liming—The hide is moved to a basic solution, created from lime, wood ash, or other alkaline substance. This loosens any hair so it can be removed, and it prepares the collagen in the hide for tanning.

- Scudding and Fleshing—The hide is placed over a shaving horse and scraped clean with a draw knife. Scudding works the top of the hide, removing any excess hair or follicles. Fleshing cleans the underside of any unwanted tissue or membranes.

- Deliming and Bating—During deliming, the pH of the hide is neutralized by soaking it in solution made with acidic minerals, urine, or other substances. Next, animal feces or entrails are added to produce enzymes that soften the hide tissue in a process called bating.

- Tanning—The hide is washed again and then tanned using tannins. These naturally occur in the bark of many types of trees including oak, chestnut, and hemlock. The tannins bind to the collagen in the hide, making it more flexible, less water soluble, and more resistant to decay. The hide is submerged in a bath of tannin liquor for many months. It may be removed at times for further scudding and fleshing, depending upon the state of the hide.

- Drying—The hide is pulled from the tannin liquor, stretched tightly, and dried. It is now leather.

- Currying—Tallow or oil is worked into the leather to make it flexible and softer. It is shaved down to the desired thickness, beat, and burnished until it reaches finished quality.

Michael’s inventory is notable because it makes no mention of large tubs, which would have been necessary for soaking the hides. This suggests that the Hagenbuch Tannery had pits or vats that were dug into the ground. The remains of these may be buried at the homestead property.

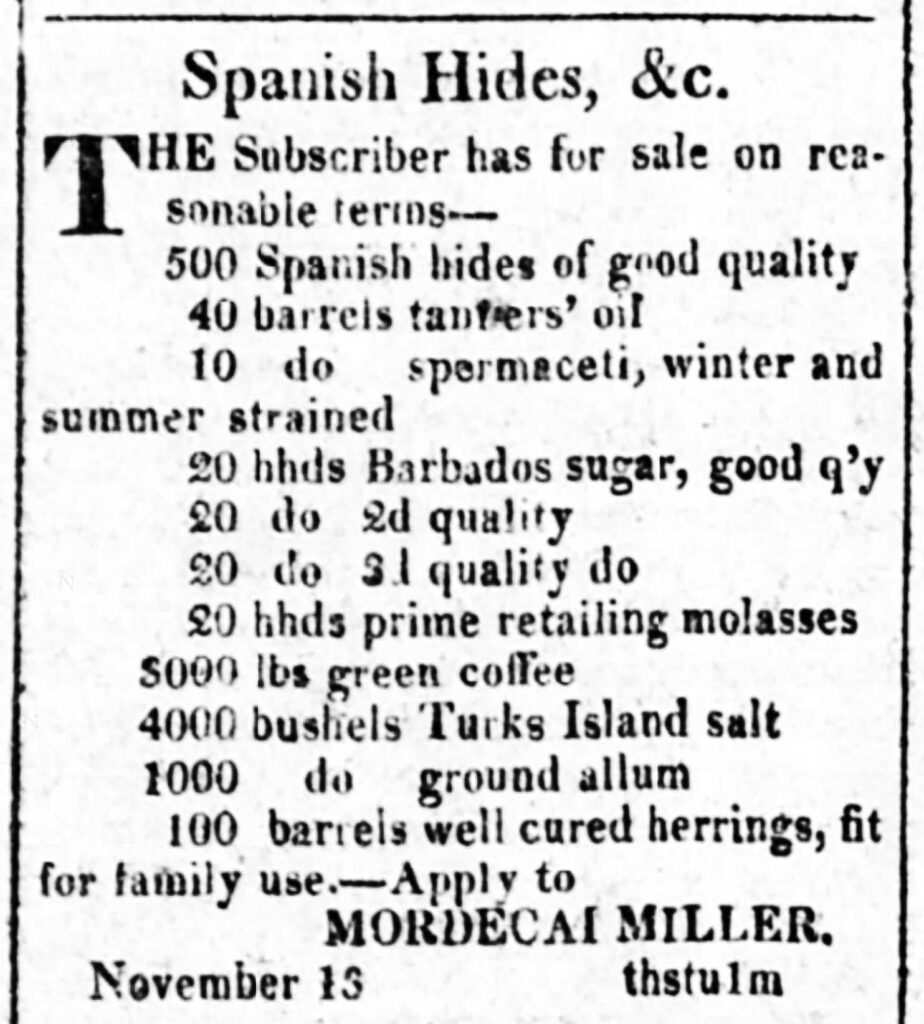

The 1809 inventory also mentions “Spanish hides.” In a previous article, research suggested that these were high quality and valuable. A new investigation has yielded several advertisements from the early 1800s that mention Spanish hides. These confirm that the hides were typically of good quality and they were imported from either Spain or its colonies. In other words, the Hagenbuchs were buying the dried, cured Spanish hides and turning these into leather.

Advertisement for imported products including Spanish hides from the “Alexandria Gazette,” November 24, 1817

Curiously, Michael’s brother, John (b. 1763), was listed as a saddler on the 1788 federal tax list for Allen Township, Northampton County, PA. He was living with his brother, Christian (b. 1747), at the time. John’s status as a saddler suggests that he was trained in leather working, an interest he may have developed at the family homestead.

While Michael was a tanner, he also was a distiller. When his son, Jacob (b. 1777), took over the Hagenbuch Homestead in the early 1800s, small-scale distilling was on the decline. As a result, Jacob—who was also a tanner by trade—appears to have boosted the production of leather at the tannery. The larger operation required more tanbark, and Jacob bought 88.5 acres of mountain land for this purpose. When Jacob died in 1842, his inventory recorded the following items related to tanning:

- a number of tubs

- saddler’s tools

- knife for scraping hides

- a set of tanner’s tools

- lime and hair

- lime bucket and shovel, etc.

- tallow and a box

- 8 cords of bark

- 25 sides of sole leather

- 29 calf skins

- 32 sides of leather

- a quantity of leather

The above list includes a large amount of different types of leather. In particular, calfskin was valued for its softness. Cords of bark are noted and were necessary for the vegetable tanning process. As Jacob grew and expanded the Hagenbuch Tanyard, his sons learned to make and work with leather. Enoch writes in his family history about how he owned a bridle made by his brother, Timothy (b. 1804), from leather tanned by their father, Jacob.

Another of Jacob’s sons, Michael (b. 1805), took over the homestead after his father’s death. According to his brother, Enoch, Michael was both a teacher and a tanner. Yet, when he died in 1855, his inventory showed little evidence of tanning. It included:

- 1 bucking tub, etc

- 1 lot tallow

- 1 lot tubs and barrels

- 1 shaving bench, etc

- 1 lot tubs and buckets

- 1 lot saddler tools

Gone are the many tanner’s tools and knives that were so clearly noted in earlier inventories. There is a shaving bench for currying and a bucking tub for liming hides. However, as was mentioned in a previous article, the bucking tub could just have easily have been used for washing clothes.

Here it is worth considering that the homestead property was divided in 1842 and Michael built a new house and barn in 1851. It seems likely that he abandoned the earlier tannery and, if he was tanning, it was mainly for the use of his family. What had once been a thriving industry for the homestead was replaced by other agricultural activities. Enoch confirms the demise of the tannery and, writing in the 1880s, describes how it was left for ruin.

Using estate inventories, an old map, and Enoch Hagenbuch’s family history, it is possible to trace the development of the Hagenbuch Tanyard from the late 1700s to the early 1800s. Similar to linen production, leather tanning was once an important, successful business for the family. But, as with textiles, industrialization would change the economics of small-scale tanneries, like the one at the Hagenbuch Homestead, and force most to cease operations

Articles in the Homestead Economics Series:

Great article, Andrew! Very interesting.

I knew there was a lot of hard work involved, but did not know how much time was involved. I believe Jacob died in 1842, not 1742 as stated.

Thanks, Uncle Bob! Yes that was a typo and it is fixed now 🙂

Thank you for your amazing summation of the life and times of a colonial tanner. My relatives, the Scholl and Winey families of Richfield, PA, were also in the tanning business. I have often wondered what they did all winter when their vats were frozen…other processing steps no doubt. To your list of leather products, you might add, as I have recently discovered, fire buckets. Not only were they made for the early fire departments, but they were also required in each home in Phila. to extinguish a kitchen or fireplace fire before it got out of hand. Of course, B. Franklin was involved in that idea!

Thanks and that is a great point about winter! Perhaps the chemical content in the water kept the vats from freezing easily? Not sure. I have seen pictures of indoor vats, but that seems unlikely in a small, rural operation. Thanks for the tip on fire buckets too!

Great article. This is off the topic but I noticed in the 1854 map a place marker for “C. Allemaengel” suggesting to me that it is a surname. Any truth to that?

Hi Bruce. Good question! I have looked at this over the years and come to the conclusion that it is a mistake. I have never seen Allemaengel as a surname. Rather, just a name for the area. The location marked at “C. Allemaengel” is where the Zahner family is known to have lived.