Homestead Economics: Flax, Linen, and Other Fibers

In 18th-century America, before cotton was king, flax was the fiber that ruled the fields. Used to weave linen fabric, people depended upon quality flax for a number of textile products—shirts, tablecloths, breeches, sheets, drawers, and more. Low-grade fibers were used to make coarse linen yarn and tow for starting fires. The seeds from the flax plant could even be collected, crushed, and their linseed oil extracted. Yet, for all of its uses, flax production was already in decline by the early 1800s.

Flax was an important crop at the Hagenbuch Homestead. It’s unclear exactly when Andreas Hagenbuch (b. 1715) began to grow it. However, it stands to reason that flax was likely first planted there in the 1740s, since the family would have needed it for their own use. In time, production multiplied as the demand for linen textiles increased in the colonies. When Andreas died in 1785, his estate inventory included a substantial amount of linen fabric, 87.5 yards total:

- nineteen yards of fine flax linen

- twenty yards of linen

- fourteen and a half yards of linen

- five yards of toile linen

- twenty nine yards of coarse linen

How much flax did Andreas have to grow and process in order to create 87.5 yards of linen? Using modern data for flax yields, it could have been as little as one and a quarter acres. But, it is assumed that colonial agriculture methods were nowhere near as efficient as today’s. This means that probably two or more acres of cultivated flax were needed. Research also suggests that a colonial family might have required one or two acres of flax just for its own needs. Therefore, if the Hagenbuchs were using flax as a cash crop, they may have had five or more acres of the plant growing at the homestead.

A print depicting a family breaking, scutching, and hackling flax by William Hinks, 1783. Credit: Notre Dame University

Curiously, Andreas’ inventory lacks any evidence of the tools needed for processing flax, wheels for spinning it into yarn, or looms for weaving it into linen. One explanation is that Andreas sold the majority of his land and estate to his sons Michael (b. 1746) and Christian (b. 1747) in 1783. Andreas only kept a small number of personal effects.

His inventory notes several different types of linens: fine, toile, and coarse. Fine linen might have been used to sew a shirt or tablecloth. Coarse, with its rougher texture, could be made into work clothes and aprons. The most interesting linen listed, though, is toile (pronounced “twall”).

Toile, from the French for “canvas”, was a linen fabric that was suitable for printing a pattern upon. The patterns were intricately designed and often of pastoral scenes. It is not believed that the Hagenbuchs were producing printed toile. Instead, they likely made the toile linen and supplied it to a tailor or textile printer in a larger city. There exists some evidence for this theory. Andreas’ son, John (b. 1763), was apprenticed to a prominent Philadelphia tailor, Andrew Hertzog (b. 1730).

During the 18th century, textiles were the single largest import from Great Britain to the American colonies. That began to change after the French and Indian War, as more Americans supported independence. Many colonies encouraged their citizens to grow flax, raise sheep, spin yarn, and weave fabric. The goal was to boost the American textile industry and reduce its reliance on British textiles. It is probable that the Hagenbuchs, who were known patriots, increased their own flax production as a result.

Even so, there is no evidence that Andreas or his children wove linen. They grew flax and may have processed it into yarn. With four sons and seven daughters, Andreas had an ample workforce for this type of labor. Weaving, on the other hand, was a specialized trade performed mostly by men, and none of Andreas’ sons appear to have been weavers.

A print showing women spinning, reeling, and boiling linen yarn by William Hinks, 1783. Credit: Notre Dame University

However, tax records show that several neighboring families had men who were—the Kistlers, Drums, Dietrichs, Kneppers, and Baileys. Some would even intermarry with the Hagenbuchs. One can imagine the people of Albany Township, Berks County, PA trading their raw materials and services to produce linen and other textiles.

Linen was a valuable commodity, especially during the Revolutionary War period when British goods were no longer available. Andreas’ inventory notes that 20 yards of linen were worth the same as 30 gallons of brandy!

Flax continued to be cultivated at the Hagenbuch Homestead, even after Andreas was gone. When his son Michael (b. 1746) died in 1809, a new inventory of the property was done. This listed:

- seventeen yards of flax linen

- fourteen pounds of tow yarn

Michael was a tanner by trade and, while it appears some flax was grown, this may have been just for the family’s needs. Unlike his father, Michael’s son Jacob (b. 1777) seems to have been more invested in textiles. In fact, there is evidence that he and at least one of his sons had some training as weavers. Jacob’s estate inventory from 1842 shows:

- flax break

- one scutching mill

- a quantity of flax

- one piece of tow fabric

- three spinning wheels and a reel

- two hackles

- a quantity of linen fabric

- a quantity of hackled flax

- loom and harnesses

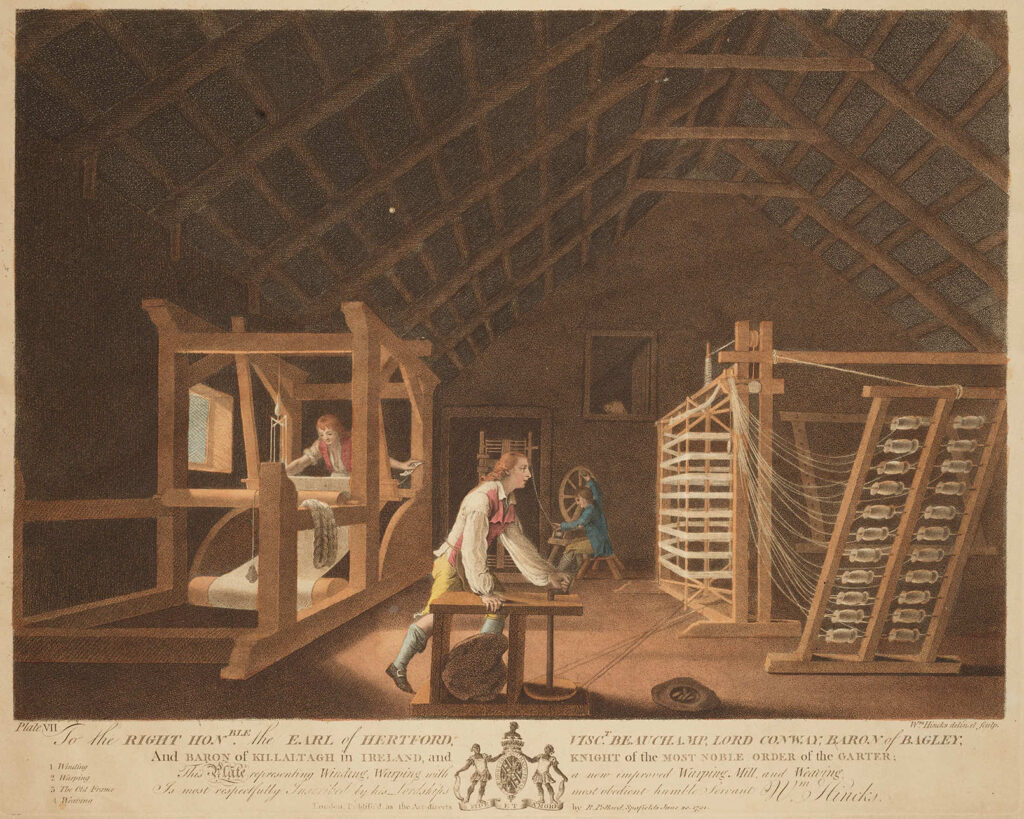

A print showing men winding, warping, and weaving linen by William Hinks, 1783. Credit: Notre Dame University

These items make it very clear that Jacob was growing flax, processing the fibers, spinning these into yarn, and weaving this into linen. The entire process, start to finish, was labor intensive and required the following steps:

- Planting—Flax needs rich soil and depletes it quickly. Crop rotation is necessary.

- Growing—Flax seeds are sown in April. Plants that are closer together branch less and grow taller, as much as three to four feet. This makes for longer, straighter fibers and better yarn for weaving.

- Harvesting—The flax plant matures in about 100 days. Plants are then pulled from the ground and laid out to dry.

- Rippling—To remove the seeds, the dried plant stalks are pulled through coarse combs. The seeds are collected, and the remaining stalks are now referred to as straw.

- Retting—This step requires specialized knowledge to be done correctly. To loosen the flax fibers from the stalks’ woody outer sheath and inner core, the straw must be exposed to moisture. Dew from the air, a pond, or a slow moving stream can all do the job. Some sources say a stream is the best way to ret flax, and a creek does run through the homestead property.

- Drying—With the fibers loosened, the retted straw is laid out to dry again, this time until is it entirely free from moisture.

- Breaking—The dried, retted straw is placed is in a wooden machine that breaks the woody parts away from flax fibers.

- Scutching—The flax is beaten with a large wooden knife to remove woody matter, leaving behind only the soft, flax fibers

- Hackling—The flax is pulled through combs that straighten the fibers, separate out shorter ones, and remove any other impurities.

- Spinning—The longest flax fibers are spun into fine, linen yarn. Shorter fibers become tow and can be spun into a coarse yarn.

- Reeling—The yarn is converted from a cone or cylinder shape into a hank.

- Weaving—Hanks of yarn are woven on looms into linen fabric.

Flax was still being cultivated at the homestead when Jacob’s son, Michael (b. 1805), died in 1855. The 1856 inventory of his estate included:

- keg flax seed

- one lot flax

- flax

- linen cloth

- one piece brown linsey

By the mid-1800s, southern plantations were growing cheap cotton by using slave labor. Processing, spinning, and weaving cotton textiles had been industrialized on a massive scale, driving down costs further. Homespun, time-consuming linen production simply couldn’t compete and families, like the Hagenbuchs, switched to other crops.

Why then would Michael still have a keg of flax seeds? One idea is that the Hagenbuchs planted flax for its oil. Linseed oil had properties that made it useful for finishing wood, treating leather, and making paints. All of these would have been needed at the Hagenbuch Homestead.

There were several oil mills near the homestead too. Michael Fenstermacher built an oil mill near Lynnville, Lehigh County, County, PA sometime before 1781. Jacob Greenawalt established an oil mill in Weisenburg Township, Lehigh County, PA in the 1740s. One of his relatives, Abraham, married into the Hagenbuch family and, another relative, John, established an oil mill in Albany Township by the early 1800s.

Michael’s inventory also mentions a curious textile: linsey. Linsey-woolsey was a coarse fabric woven from linen and wool. The linen was used for the warp of the fabric (the long, vertical threads) and the wool was used for the weft (horizontal threads woven through the warp). This design gave the textile the strength of linen with the feel of wool.

We know that sheep were present at the Hagenbuch Homestead throughout the 18th and 19th centuries. Along with flax, their wool was almost certainly used to make textiles. Another example can be found in Jacob’s inventory which lists:

- a quantity of satinette

Satinette or “satinet” could be called commoner’s satin. Instead of being made from silk, satinet was woven with a warp of linen or cotton and a weft of wool. This sounds a lot like linsey-woolsey, except that satinet was finely woven to mimic some of the qualities of satin. Research suggest that during the 19th century satinets were produced using quality wool, such as that from merino sheep, and a twilled weave pattern.

Flax and wool were important fibers grown at the Hagenbuch Homestead. Flax was used to make linen, while wool could be combined with linen to create linsey-woolsey and satinette. Textile weaving was not always done on the farm, and only Jacob Hagenbuch was documented as owning a loom. However, the economic necessity of flax at the homestead, whether for its fibers or its oil, is undeniable. Understanding how and why flax was cultivated there helps us to better imagine the daily lives of our ancestors.

Articles in the Homestead Economics Series:

Andrew, Are you aware of the PA Agrcultural census? The first was done in 1850 and will have valuable info about the Hagenbuch farm in Albany Twp. Info is online. I can send you the link if you don’t have it. Chris W.

Hi Chris. Wow! I haven’t seen this. I believe this is it? https://www.phmc.pa.gov/Preservation/1850-Agricultural-Census/Pages/Counties-A-J.aspx This will be useful for future articles as it captures the Hagenbuch Homestead shortly before it was sold out of the family.

You got it.

Michael has 10 bushels of flaxseed and 2 lbs of silk cocoons. Go figure. To really make sense of any of this, one has to compare farms against one another, which would take some time to do a spread sheet to organize things of all the farms in Albany Twtp.

As you may have seen, there is also an 1880 and 1927 census, which may be helpful for other Hagenbuch farms elswhere.

Hi Chris. This is a great idea. I might dig into this and use it more for my next piece. I wanted to write about either the tannery, distillery, or general agriculture of the homestead. This find gives me a good primary source for the latter, along with some of the family letters we have from that time 🙂