Hagenbuch Coat of Arms Revisited

In early June, Andrew received a message from Jacob Robison who asked some questions about our family’s DNA tests and also about the Hagenbuch coat of arms. He was curious if we had any more details about the depiction of the beech tree and fence, which is the symbol of the town of Hagenbuch in Switzerland. We use its visuals to explain our surname: “Hagen” being the fenced enclosure and “Buch” referring to the tree. Several articles have already been written about this subject including the Story of the Buchbaum, Hagenbuch Coat of Arms, and Are We Really Beech Trees? The coat of arms that the town of Hagenbuch uses as their symbol is the most definitive emblem that our family can use, well, almost. Let me explain.

Let me begin by defining coat of arms as it can be a very confusing subject. A coat of arms is the shield portion which we see “knights of old” use and is surrounded by a crest, a motto, supporters, and helmet. A coat of arms is awarded to an individual, not to a family. However, there are some instances when the complete “arms” can be passed on, such as with Scottish clans.

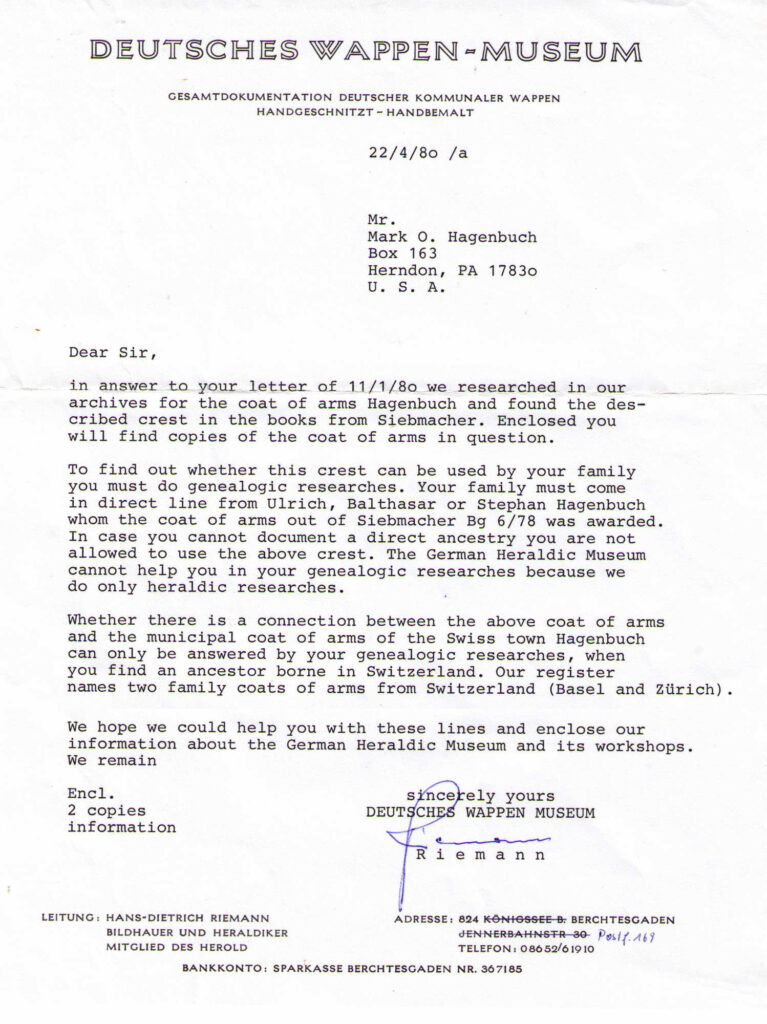

For example, the symbol we use as a family coat of arms (the beech tree and enclosure) can legally be used by members of the Hagenbuch family if they are descended from the brothers Ulrich, Balthasar, Stephen, and Georg Hagenbuch who were awarded the arms in 1541. They were bestowed (from translation) by the “emperor” who, at that time, was Holy Roman Emperor Charles V. Arms were awarded for some sort of bravery or service provided by the recipient. All this was documented in 1980 by Hans-Dietrich Riemann, director of the Heraldic Museum in Germany. Dr. Riemann further states in his letter that he is not sure of a connection between the Hagenbuch brothers’ receipt of the coat of arms and the town of Hagenbuch in Switzerland.

Americans, in particular, tend to be obsessed with finding a connection between their family and ancestors who would have had a coat of arms presented to them. Many Americans want to have someone famous in their background and with that comes the trappings of royalty, especially in the form of a coat of arms. Early on in my genealogical research, that was me too! I wanted to find a connection between our patriarch, Andreas (b. 1715), and those four brothers who were, according to one reference, “noblemen in their rights.” I never found that connection, although it is a possibility.

In the meantime, the symbol of the beech tree from the town of Hagenbuch became the stand-in symbol which I used. We do know that there were families of Hagenbuchs in the area of Switzerland, northeast of Zürich, and that Andreas’ great grandfather, Hans Sr., left there for Germany in 1652. But, was our line of Hagenbuchs familiar with the beech tree and enclosure as a symbol of the family and were they connected to the town of Hagenbuch?

Soon after Andrew received the message from Jacob Robison (which brought back a lot of memories of my early research on a Hagenbuch coat of arms), Andrew found new information that has given new life to this search. A stained glass window, which was being auctioned off in 2017, connects two brothers living in Zurich in 1674 with the coat of arms we know—a fenced enclosure and beech tree. What Andrew found was all in German, but he had it translated in two sections. First was the description of the stained glass window:

Switzerland, dated 1674. Signed “I.Weber”. Jakob Weber II (1637–1685), glass painter from the Zürich area. Glass etched and polychrome painted. In lead frame. Central image: Between 2 columns the helmeted coats of arms of Hans Heinrich and Georg Hagenbuch and their wives. Top: Prophet Isaiah, surrounded by 3 evangelist symbols and 3 scenes on the theme of “Fountain of Life”. Cartouche with inscription. At the foot 2 inscriptions and year. 30×20 cm. In wooden frame. Some cracks and cracked lead. Small addition in the left inscription (bottom).

This was followed by a translation of the inscriptions in the stained glass:

On the top: “Fons Vitae. With the fountain of life, God’s grace gift from heaven, refreshes the soul, makes it fertile, green flows there and from there, waste water and stinking sludge, and also dispels the false teachings.” On the bottom: “Hans Heinrich Hagenbuch, citizen of the city of Zürich, pastor of Veltheim and Mrs. Susaja Bodmeri, deceased, and Mrs. Esther Lindineri, his wife. Anno 1674” and “Georg Hagenbuch, citizen and councilor of Frauw, at that time judge of the noble foundation of Münster in Argoüw, Mrs. Margaretha Seengerin, deceased, and Mrs. Anna Maria Düllin, his wife. Anno 1674.”

There is a lot to learn from the translation and especially from the stained glass window itself. What struck me most at first glance was the use of the beech tree throughout the window: two times depicted without the fenced enclosure and two times depicted with the enclosure. It can also be found at the bottom left with a unicorn. To me, this means that these two Hagenbuchs, probably brothers—Hans Heinrich, a pastor, and Georg, a judge—were using the symbol of the town of Hagenbuch as their own symbol, possibly to symbolize their Hagenbuch clan. Two of the other symbols, the unicorn and the lion, are used in the coat of arms that was sent to me years ago when I was first researching the possibility of a Hagenbuch coat of arms. I find it interesting that the lion seems to be holding a cross. This is possibly a symbol of a medal of service that was given to the four brothers back in 1541.

Other symbols found in the stained glass are the mullet, a German six pointed star, which is in the same shield as what appear to be plant leaves or “spades” as in playing cards. In heraldry, the use of the spade represents a leaf and therefore life. There is also a crescent moon with a three leaf clover symbol, as well as two more mullets. The color blue is predominant and again, from the information sent to me years ago, the background color of the shield that the four Hagenbuch brothers received was blue or azure.

The religious symbols of Isaiah and the “fountain of life” reference are most likely meant as just that—religious references not related necessarily to the Hagenbuch family. However, the scenes around Isaiah are exceptionally busy: animals in an ark, a figure with an eagle atop a cross with strings and mirror, a prostrate figure, and men digging. All of this needs further research to decide the significance of all these figures and their relationship to the inscription of “Fons Vitae” and Isaiah.

The locales mentioned are from different areas around Zürich, and one can’t be sure why they are part of the inscription when Hans Heinrich and Georg were probably from Zürich. What was very mysterious to me was the mention of four women and the words “his wife” for both brothers. However, thanks to Mr. Jean McLane—who has previously assisted us in translating German to English—we now know the answer.

The German word “selig” actually means “deceased” in this context. Therefore, the inscription, after naming Hans Heinrich and Georg, is indicating that two of the women had died and the brothers had remarried the other two. Of course, it is strange that they are referred to with “Mrs.” and their maiden names. But, this gives us information about the four wives’ ancestry: Mrs. Susaja Bodmer, Mrs. Esther Lindner, Mrs. Margaretha Seenger, Mrs. Anna Maria Dull. Note that in German, endings of “in” and “i” are not part of a surname and denote a female.

Mysteries and curiosities abound in this stained glass window. Most significant is that the coat of arms of the town of Hagenbuch was being used by two Hagenbuchs in 1674, a mere 20 years after Andreas’ great grandfather left this area to move into Germany in 1652. It would be advantageous if our patriarch, Andreas, could be genealogically connected to the four brothers—Ulrich, Balthasar, Stephen, and Georg—from when the enclosure and beech tree first appear to be associated with our Hagenbuch family in 1541. It would be equally advantageous if Andreas could be linked to the two brothers that were the patrons of this artistically beautiful stained glass window. One has to wonder: Who purchased the window in 2017? Does this person have a connection to the Hagenbuch family, as they might have information about Hans Heinrich and Georg?

Andrew’s discovery is exciting for it not only connects our Hagenbuchs to the use of the Hagenbuch town symbol, but also serves as a missing link between Hagenbuchs from Zürich and our own Hagenbuchs from nearby. The stained glass window is an artistic and colorful reminder that our family is much more than just the black and white letters of the typed word. We are a family of colorful stories now supported by a magnificent piece of art.

Many thanks to Jean McLane for his translations from German to English.

How did you find out who the coat of arms had last been issued to or when last issued? Was it the German wappen-museum that was able to give you that information?

I found a coat of arms drawing with my family name on it in with a genealogy book we have of our family from the generation before the one that came to America from Germany. So trying to figure out if a decanted of mine was issued it but not sure how to find that information.

Not sure if your aware but Hagenbuch and Hagemann surname is Hagen which has an unbelievable history in medieval Germany nobility. Having many members connecting to emperors and kings of Germany, Netherlands, Sweden.

Well any help you could give would be greatly appreciated.