Gold Fever: The Journal of J. C. Hagenbuch, Part 5

At the end of Part 4 in this series, J. C. Hagenbuch (b. 1862) and his uncle John “Jack” Hagenbuch (b. 1857) had moved their camp to an abandoned cabin near Coon Creek, California. By August 29, 1905, Jack was back to prospecting for gold, while J. C. watched over the cabin. Their Klamath River adventure concludes in Part 5. You may view previous installments here: Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, and Part 4.

JOURNAL OF J. C. HAGENBUCH

Part 5: August 30, 1905–September 5, 1905

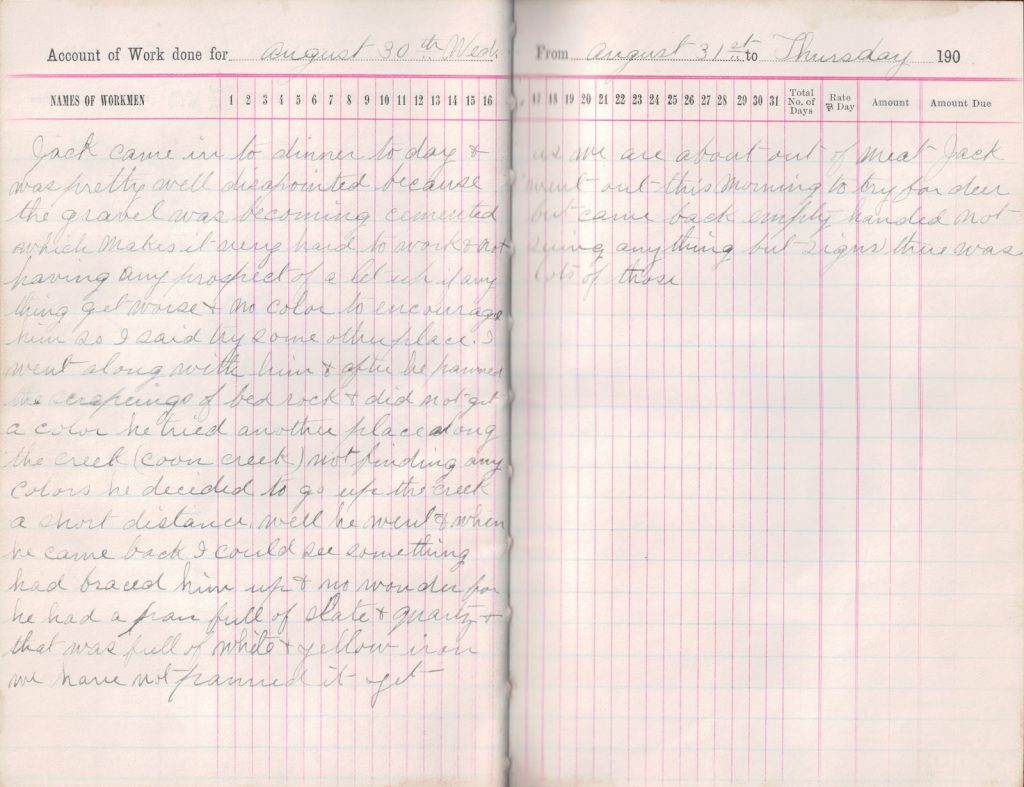

Wednesday, August 30, 1905

Jack came in to dinner today and was pretty well disappointed because the gravel was becoming cemented, which makes it very hard to work. Not having any prospect of a let up—if anything getting worse—and no color to encourage him, so I said, “Try some other place.”

I went along with him and after he panned the scrapings of bedrock and did not get a color, he tried another place along the creek (Coon Creek). Not finding any colors, he decided to go up the creek a short distance. Well he went and when he came back. I could see something had braced him up and no wonder, for he had a pan full of slate and quartz that was full of white and yellow iron. We have not panned it yet.

[Coon Creek, California: View Map]

Thursday, August 31, 1905

As we are about out of meat, Jack went out this morning to try for deer. But [he] came back empty handed, not seeing anything but signs. There were lots of those.

[Coon Creek, California]

Friday, September 1, 1905

Jack and I went up to look at this prospect as it was not very far. Then we went on up the mountain for a mile or two looking for deer. But [we] failed to see anything but lots of grey squirrels, which were too small to use our rifles on as ammunition is scarce for his gun. So I did not shoot either. We came home early. Then John panned the samples he brought in but although full of iron, we got no gold which showed up. Maybe [a] smelting proposition?1 Now Jack is down to the river trying his luck with the salmon.

[Coon Creek, California]

Saturday, September 2, 1905

We both went over to where Jack found his lead and worked until dinner time. After dinner, Jack went back to work while I went down to Elliot’s—a half-breed (who runs a little store and who by the kindness of his daughters sees to sending and getting our mail).2 Well I received 5 letters while Jack got 12, and he has been reading letters ever since. Then on the way, I saw lots of salmon running, and we quit and went to the house. We got the gig, but that is all we did get.

[Coon Creek, California]

Sunday, September 3, 1905

After breakfast, we went down to look for salmon again. While Jack went down along the bank to see just where they came up, I counted 19. Then I called him, and up to the time he came back, 10 more went over. I told him, and he started in. But, it seems every time he would go in, they would quit running. So he stayed in but not one came. We came to dinner, and I fixed up a gig for myself but did no better for neither one [of us] got a fish.

[Coon Creek, California]

Monday, September 4, 1905

Jack started out after deer as we are out of meat, but [he] did not get any so [he] got back for a late dinner. Then we went after salmon and got the same amount.

[Coon Creek, California]

Tuesday, September 5, 1905

We went over and worked until dinner time. Then [we] brought some of the iron along back. After running some quicksilver through it, we burned it to see if it caught any gold.3 But when it got hot, it all blew away. So we do not know whether we had any or not.

[Coon Creek, California]

POSTFACE

J. C. Hagenbuch’s story of traveling down the Klamath River in search of gold begins on July 9, 1905 and ends abruptly on September 5, 1905. His final entry is written on the last page of the journal, and to date a second journal has not been found. This begs the question: What happened next?

From the journal, we know that J. C. and Jack made it as far as Coon Creek, California. We also know that they were having poor luck finding much gold. This fact is highlighted in J. C.’s final entry when he mentions using mercury (also known as quicksilver) to capture gold from iron ore. Like a comedy of errors, the heated mixture blows away, leaving them with nothing.

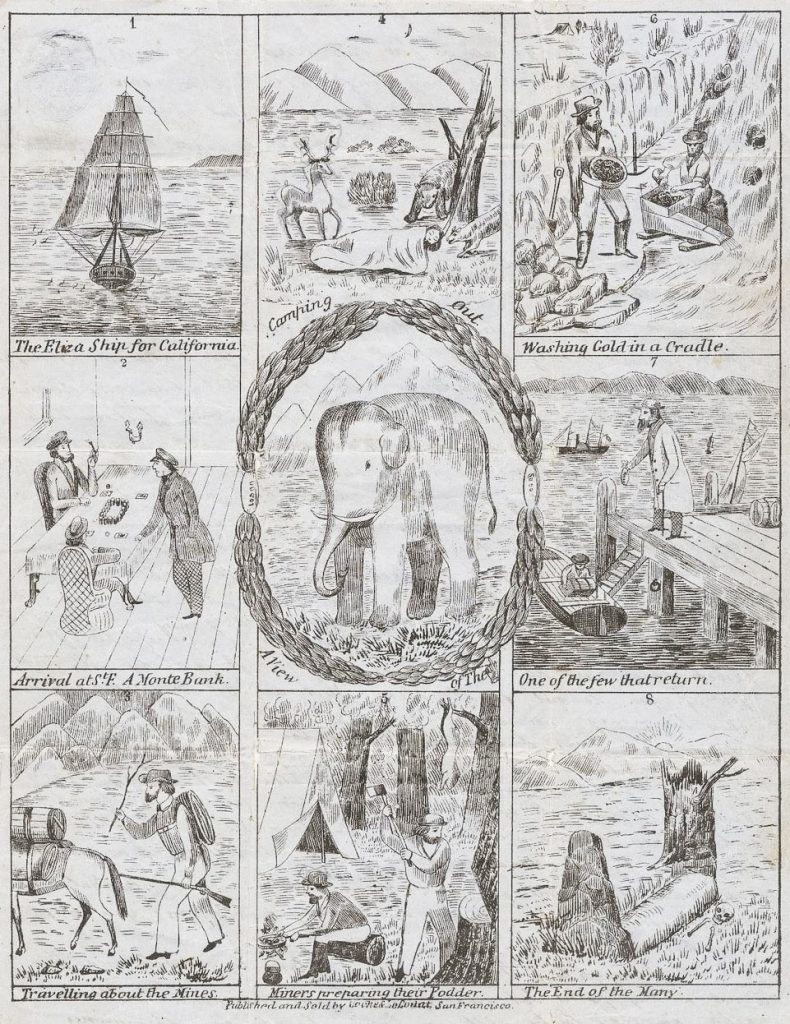

Compounded by the pair’s dwindling supply of food and low ammunition reserves, it seems that their adventure may have been drawing to a close. One can imagine that after another few weeks of unsuccessful prospecting, they loaded up their boat and continued down the Klamath River towards the Pacific Ocean. Once reaching a larger town with a train station, they may have sold the boat, said their goodbyes, and returned to their previous lives. It might be said that Jack and J. C. had “seen the elephant.”

Scenes of the gold rush including “seeing the elephant”, c. 1852. Credit: UC Berkeley, Bancroft Library

“Seeing the elephant” was a popular figure of speech during the 1800s. The phrase was used to describe an experience that one anticipates with great excitement, but which ultimately leads to disappointment or hardship. For example, during the California Gold Rush of the mid-1800s, unsuccessful miners wrote of “seeing the elephant” and never needing to “see” it again. Similarly, soldiers in the Civil War used the phrase to describe their experiences of battle.

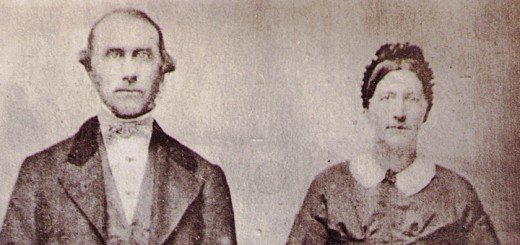

By 1908, Jack was once again living in Victoria, British Columbia. According to a newspaper advertisement in The Victoria Daily Times, he had resumed work as a sign painter. In 1921, documents show that he crossed back into the United States at Buffalo, New York. These records list his daughter, Emily (Hagenbuch) Leslie, as his point of contact and mention he was traveling to visit his nephew, J. C. Hagenbuch.

John “Jack” Andrew Hagenbuch died on April 7, 1923 in San Francisco. It is believed his was living there with his daughter, Helen Hagenbuch. He is likely buried somewhere in Northern California.

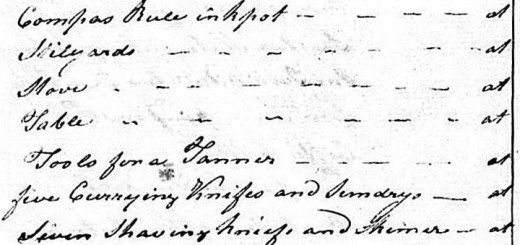

Advertisement for J. A. “Jack” Hagenbuch’s sign painting services in The Victoria Daily Times, September 1908.

J. C. Hagenbuch returned to Bloomsburg, Pennsylvania. According to census records, in 1910 he was living with his father Isaiah, stepmother Harriet, and sister Bertha. After his father’s death, J. C. moved to Sugarloaf Township, Columbia County, PA, where he did farm work.

Census records also reveal that beginning around 1920 J. C. resided next to Irvin and Clara Diltz. Their son, Otto, is the same one mentioned in J. C.’s journal as a cousin. J. C. and Otto appear to have had a close relationship, as it is Otto who signed J. C.’s death certificate.

Jacob Clark “J. C.” Hagenbuch died on November 19, 1930. He is buried at St. Gabriel’s Cemetery in Coles Creek, Columbia County, PA. It is believed that when he died J. C. left his possessions—including the 1905 journal—to his friend and cousin, Otto Diltz. Jim Hess, who discovered the journal, is the grandson of Otto’s sister, Anna (Diltz) Hess.

J. C.’s 1905 journal is a fascinating piece of Hagenbuch history. Not only does it document the travels of two Hagenbuchs from the early 1900s, it also provides insights into their personal thoughts and dreams of riches. Though J. C. and Jack appear to have found little gold, the real treasure is the one they left us: their story. We owe much to Jim Hess and his family for preserving this wonderful piece of our family’s heritage.

Footnotes

-

- J. C. appears have considered other mineral opportunities, such as smelting iron, in case they did not find gold.

- Elliot’s store was located in Cottage Grove, California.

- Quicksilver is another name for mercury. Gold can be dissolved into mercury, making it useful for extracting gold from other minerals. Burning the mercury will release the concentrated gold. However, this process is quite toxic.

thank you for another good read…..a lot of work…good information

You are welcome, Uncle Dave! It’s been a fun series of article to work on.