Easter Day: April 7, 1765

This article contains several quotes from Johann Arndt’s 1605 book concerning Pietism. Although I realize that the writings can be difficult to understand at times, please take the time to read them carefully and reflect as Andreas Hagenbuch would have done.

Easter Day, April 4, 2021 was the quietest Easter I have ever known. Because of Covid, there was no family gathering here at our place outside Dillsburg. We didn’t color any Easter eggs or pack colorful Easter baskets with plastic straw and candy. We didn’t attend church with the Gospel reading of Christ’s resurrection, familiar joyful hymns echoing in the sanctuary surrounded by white lilies. Church at St. Paul’s Lutheran was “zoomed”. Typed Facebook messages went back and forth, with the expected, “He is risen!” and the response, “He is risen, indeed!” We did have a visit from daughter Julie, her boyfriend Eddy, and his father. The five of us sat outside and enjoyed a delicious red velvet cake created by Linda.

During the day, my thoughts turned to Easter days that my fifth great grandfather, Andreas (b. 1715), would have spent here in America. What would he have done, for example, on Easter Day, 1765 after having been here in America for almost 30 years, with two wives and 13 children being the center of his life? Of course, any religious aspects of Andreas’ beliefs are always tempered by my belief that he was a strict Lutheran Pietist, a student of Johann Arndt and Philipp Spener. Several articles have been written about the Pietist book which Arndt wrote, Wahren Christendom (True Christianity), that was important enough to Andreas that he willed it to his youngest son, John. As a Pietist, how would Andreas’ Easter Day look compared to how Christians celebrate it now?

Some sources state that the Easter bunny and colored eggs were brought to America by German immigrants in the 1700s. Even so, I find it difficult to believe that Andreas got caught up in these Easter traditions. If he was the strict Pietist that I believe he was, Andreas would have been focused on the inward guilt of sin, the crucifixion, the suffering of Christ, and the seriousness of the resurrection. Yes, we Christians believe in the joy that Christ overcame death and that the same future is promised to us. We know that we are given the grace of God by our faith. St. Paul writes of it and Andreas would have believed in this same promise through Martin Luther’s teachings of justification through faith alone (Romans 1:17). Along with the teachings of the Holy Bible and the preachings of Luther, what did Andreas read in Johann Arndt’s book concerning resurrection? Were they the words, “Alleluia, He is risen!”?

In Wahren Christendom (Book 1, Chapter 3), Arndt writes:

Look to [Christ’s] suffering, death and resurrection. Why did he suffer this? Why did he die and rise? He did so that you might die from your sins with him and in him, with him and through him you might again spiritually be resurrected and walk in newness of life . . . The new birth arises and springs from the wellspring of the suffering, death, and resurrection of Christ . . . by the power of His death [we] arise from our sins through the power of His resurrection.

Arndt continues (Book 1, Chapter 5):

Since Christ has helped others He will help me for He is in me and He lives in me. He has made the blind to see. I am spiritually blind; therefore, he will make me also to see. Thus it is with all the miracles. Therefore, acknowledge yourself as a blind person, a lame person, a cripple, a deaf person, as one exposed, and He will help you. He made the dead live again. I am dead in my sins and, therefore, He must make me live again, so that I have a part in the first resurrection.

These are excerpts which Andreas would have been familiar with and shared with his family, reading to his wife Anna Maria Margaretha and their children who were present on Easter Day, 1765. No stories of the Easter bunny, no hunting colored eggs, and no candy in baskets. Instead, Easter morning probably consisted of father Andreas leading his family in fervent prayers, the reading of the resurrection story in all of the four Gospels, and the preaching of Arndt’s serious Pietist writings about suffering, sin, and repentance; sharing Christ’s pain with the result of resurrection.

I would hope that Andreas would have offered some Easter joy among all the Pietist guilt. Arndt does write in Book 4, Part 1 some uplifting words. To summarize:

Light, in particular the sun, is a symbol of God and of Christ. It symbolizes God’s essence, the most beautiful light, the warm love of God, and the internal, spiritual light of the soul that is Christ himself. Light brings joy, it gives us power of life, it allows us to see the truth and casts out more than reason. The sun adorns the heavens and Christ adorns the Church . . . Light shares itself with all things and God shares himself with men. The light of the sun is also an image of resurrection. We share in it as we share in Christ’s resurrection.

To me this brings the images I have of past Easter Sundays, when I attended Easter sunrise services—the sun rising in the east as the church family joyfully sang, “Jesus Christ is risen today. Alleluia! Our triumphant holy day. Alleluia!” Arndt shared not only the Pietist beliefs that can be somber but also, as evidenced above, the joy of Christ’s resurrection likened to the rising of the sun.

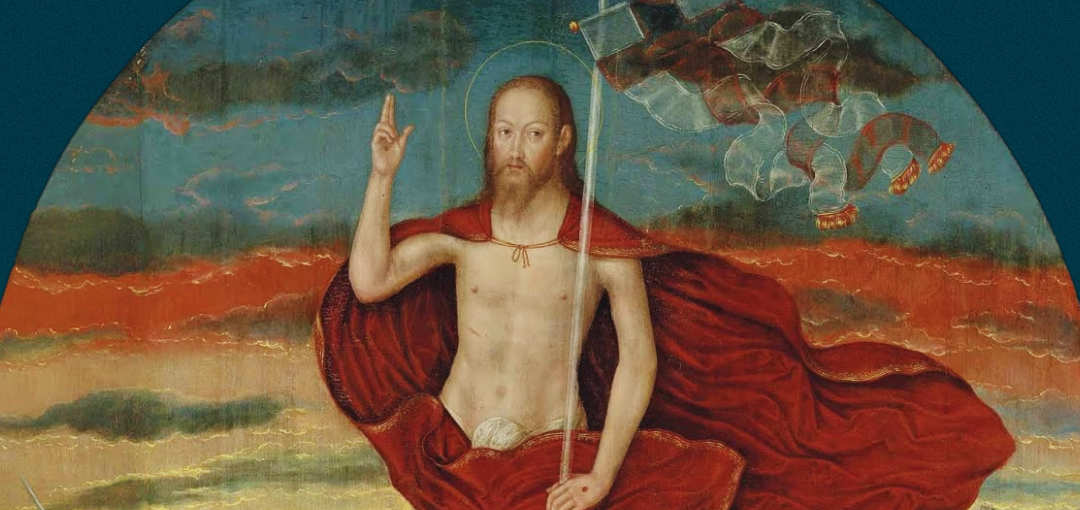

“Resurrection of Christ with Donor Family”, c. 1573, by Lucas Cranach the Younger. Cranach’s father, Lucas Cranach the Elder, was a contemporary of Martin Luther and was also a well known painter. The painting depicts the risen Christ standing on the lid of a sarcophagus and surrounded by a pious family. It bears witness to His resurrection, the tomb is empty and Christ has overcome death. It is an example of Christ’s sacrifice and suffering for mankind, a Pietist principle.

I spend a lot of my time thinking about our ancestors and their beliefs, their personalities, even picturing what they may have looked like! I have an imagination that can run rampant, especially when it comes to Andreas Hagenbuch, a man who was “big” in everything he did. Possibly “unique” is a better word. However, I do rely on my son Andrew’s realistic thoughts to tone down my imaginative musings. When I asked Andrew what he thought about Andreas and the celebration of Easter, knowing that Andreas must have believed reverently in Johann Arndt’s writings, he wrote to me:

I think it is tough to say for certain what Andreas believed or didn’t, beyond the fundamental Christian tenets. He owned Arndt’s book and appears to have valued it. He also didn’t always participate at New Bethel Church. That does lean toward Pietism. But, he may have just been independent or stuck in his ways, while the new organizations were being set up around him. I mean, someone doesn’t purposefully live in the wilderness if they have a fondness for institutional organizations and socializing, right? Maybe he was even more radical than Pietism? None of that would have survived, if true, I am sure!

So, as with some parts of our genealogical journey, we must imagine from what little evidence we have the innermost beliefs of our ancestors. It’s what makes them come alive. To me, Andreas was at once the strict religious leader of his family and at the same time a man who took care of his family and property.

Johann Arndt’s words from his Pietist teachings, Wahren Christendom (1605) which were read and pondered over by Andreas Hagenbuch, will serve as a conclusion to what Andreas may have reminded his family on Easter Sunday, 1765. These come from the book’s Foreward:

. . . Christian virtues are the children of faith, arise and grow from faith, and cannot be separated from faith at their source, if they are indeed genuine, living, and Christian virtues, arising from God, from Christ, and from the Holy Spirit. Hence no work can be pleasing to God without faith in Christ. How can true hope, proper love, constant patience, earnest prayer, Christian humility, and a childlike fear of God exist without faith? All must be drawn from Christ, the wellspring, through faith, both righteousness and all the fruits of righteousness. You must take care that you do not connect your works and the virtues that you have begun, or the gifts of the new life, with your justification before God, for none of man’s works, merit, gifts, or virtue, however lovely these may be, count for anything.

To a Pietist, Easter was certainly a serious, religious, and devotional holy day.