Discovery: 1851 Letter Between Hagenbuch Brothers, Timothy & Enoch

Early this year, an exciting piece of Hagenbuch family history was discovered – an original, 1851 letter from Timothy Hagenbuch to his younger brother, Enoch. Not only does this letter shed light upon important family relationships during the mid-19th century, it also answers questions about why the Hagenbuchs, along with other families, traveled into the American West.

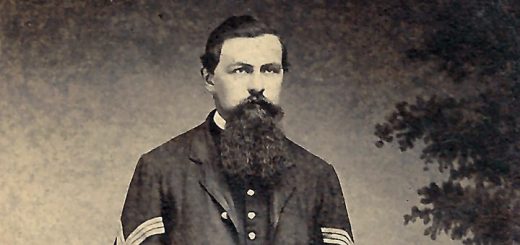

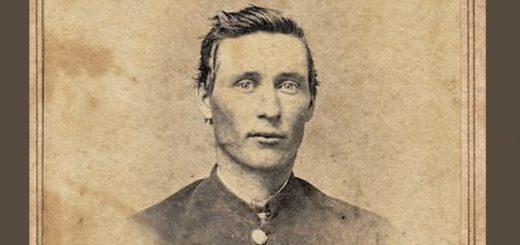

Timothy (b. 1804, d. 1852) and Enoch (b. 1814, d. 1895) have been previously featured on this website. Their father, Jacob (b. 1777, d. 1842), was a tanner and the great grandson of Andreas Hagenbuch (b. 1711, d. 1785). Both Timothy and Enoch were born and raised at the Hagenbuch homestead in Albany Township, Berks County, Pennsylvania.

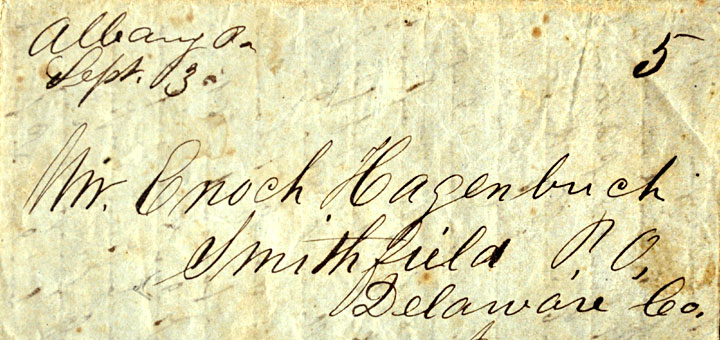

Enoch left Pennsylvania in April of 1838 and traveled west by horse and wagon. He first settled in Smithfield near the town of Muncie, Delaware County, Indiana. Then in 1852, Enoch pushed on to Waltham Township, LaSalle County, Illinois where he farmed not far from his younger brother, Charles (b. 1819, d. 1890). Late in his life, Enoch authored his History of the Hagenbuch’s in America. In this, he recorded family stories along with his own.

Unlike most of his brothers, Timothy decided to remain in Pennsylvania and stayed near to the Hagenbuch homestead. He neither married nor pursued a career in agriculture. Instead, he got an education and served as a school teacher as well as a scrivener.

Enoch’s historical account of the Hagenbuchs, written after he had moved to Illinois, frequently references the lives of family members living in distant locations. This led to speculation that he must have been in close contact with relatives living in other states. However, without email or a telephone, how was this possible?

Timothy’s 1851 letter to Enoch answers this question. The Hagenbuch family, even as it spread across the United States, shared family news and current events through written communication.

The discovery of the letter begins in Texas with a retired teacher named Jean McLane. Jean’s interest in old German writing led him to purchase the letter, which had been offered for sale on eBay. The eBay seller, located in Massachusetts, had acquired it as a part of a collection of miscellaneous antique letters.

After receiving the letter from the seller and translating it into English, Jean went looking for information about the people it mentioned. Ultimately, an online search for “Enoch Hagenbuch” led him to this site, at which point he made contact.

Jean generously donated the 1851 letter along with his translation to the Hagenbuch archives. It goes without saying, but were it not for Jean’s thoughtfulness the letter might have gone undiscovered. Thanks to his caring efforts this artifact can now be shared with the Hagenbuch family and others.

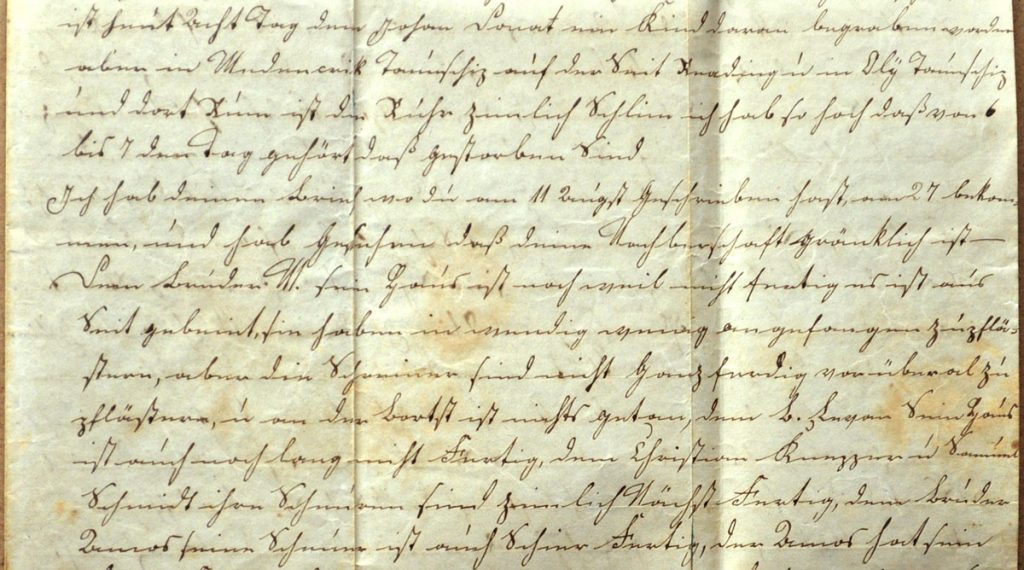

Upon examining the letter from Timothy to Enoch, several elements immediately stood out. First, the letter includes writing in English and Pennsylvania Deitsch. This confirms that some 120 years after arriving from Germany, the Hagenbuch family was still using a form of German to communicate with one another.

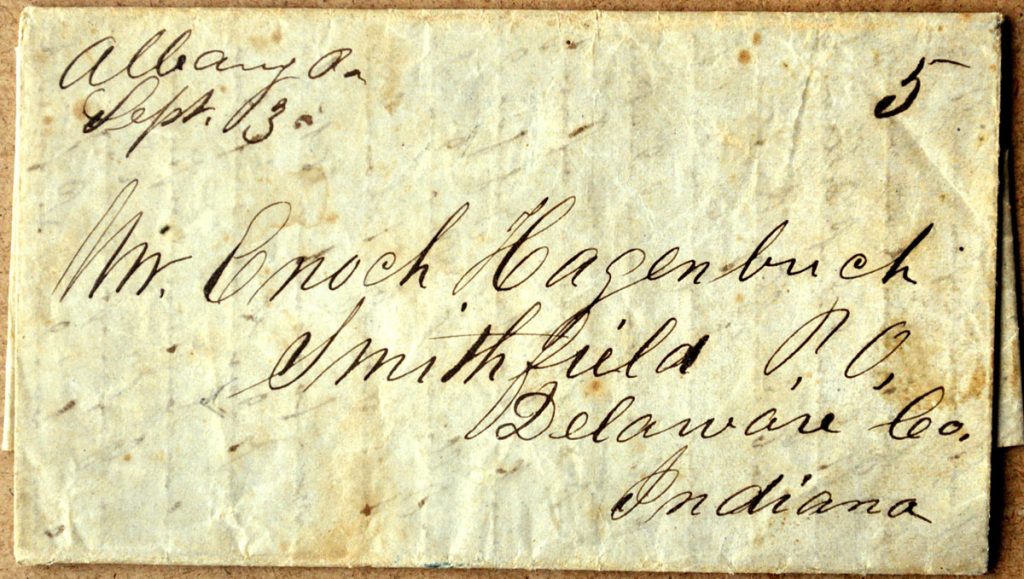

Nevertheless, some fluency in English was required to function in the broader American society, and Timothy, as a school teacher, undoubtedly was fluent in it. Sure enough, the address on the outside is written in perfectly legible English cursive. The inside, however, is in Deitsch using an old German writing style known as Kurrentschrift.

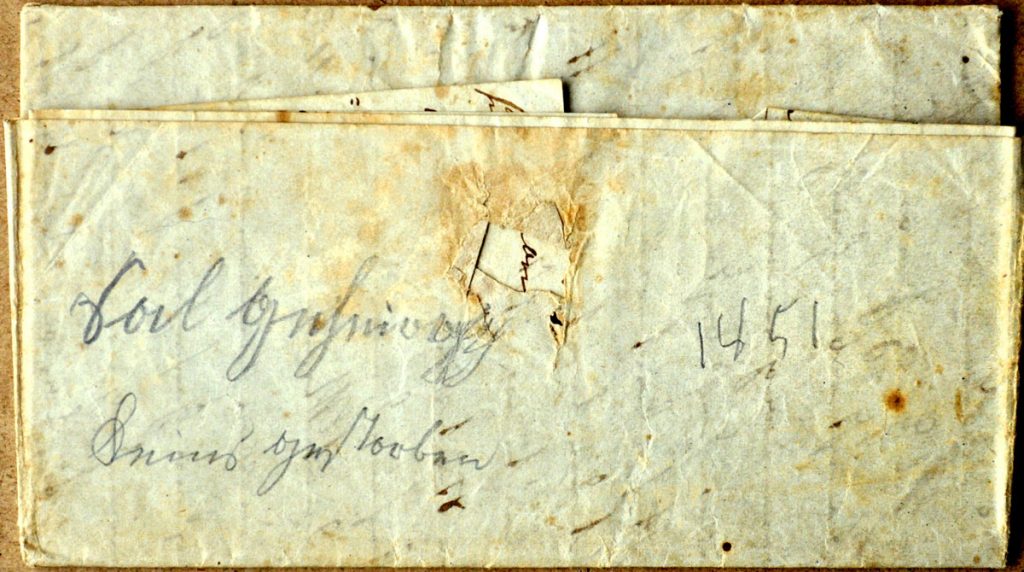

Another item worth noting is the letter’s lack of an envelope. As was commonplace during the 19th century, letters were written on sheets of paper which could be folded and closed with a wax seal or adhesive sticker. The evidence of such a seal can still be seen as a torn hole on the back of the letter.

One final detail that stands out is the letter having two different forms of writing on the outside. The English mailing address on the front is written in ink and was almost certainly put there by Timothy. The penciled Deitsch text on the back appears to be written by someone else, and as will be discussed later, may have been Enoch jotting down a few notes about the letter’s contents.

Timothy’s 1851 letter to Enoch is a fascinating reminder of what a single artifact can reveal about family. The next few articles in this series will further examine the contents of the letter and provide an English translation of what Timothy wrote to his brother.