The Deaths of a Father and Son

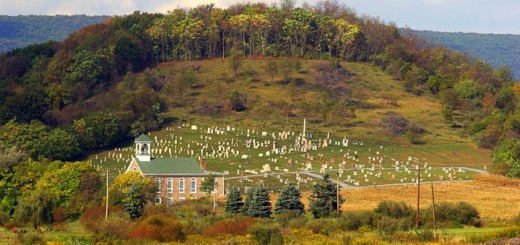

I have been inside the house on the hill twice. It overlooks the Susquehanna River. Both times, as I walked through the first floor rooms, up the two stairways, through the hallways, and into the bedrooms, I have thought of my family living there almost 125 years ago. I can see the children and my great grandparents. And, I can sense the pallor of death that descended on this house in 1897.

The scenes of this article set inside the house are fictional, based on the facts we know surrounding the deaths of Hiram and Henry Bruce, and from the physical tours of the house.

The date was July 10, 1897. The place was just north of Milton, Pennsylvania in the house on the hill that had only been completed about six months previous. The atmosphere within the house was depression, mournfully silent, a deathly pall hanging within.

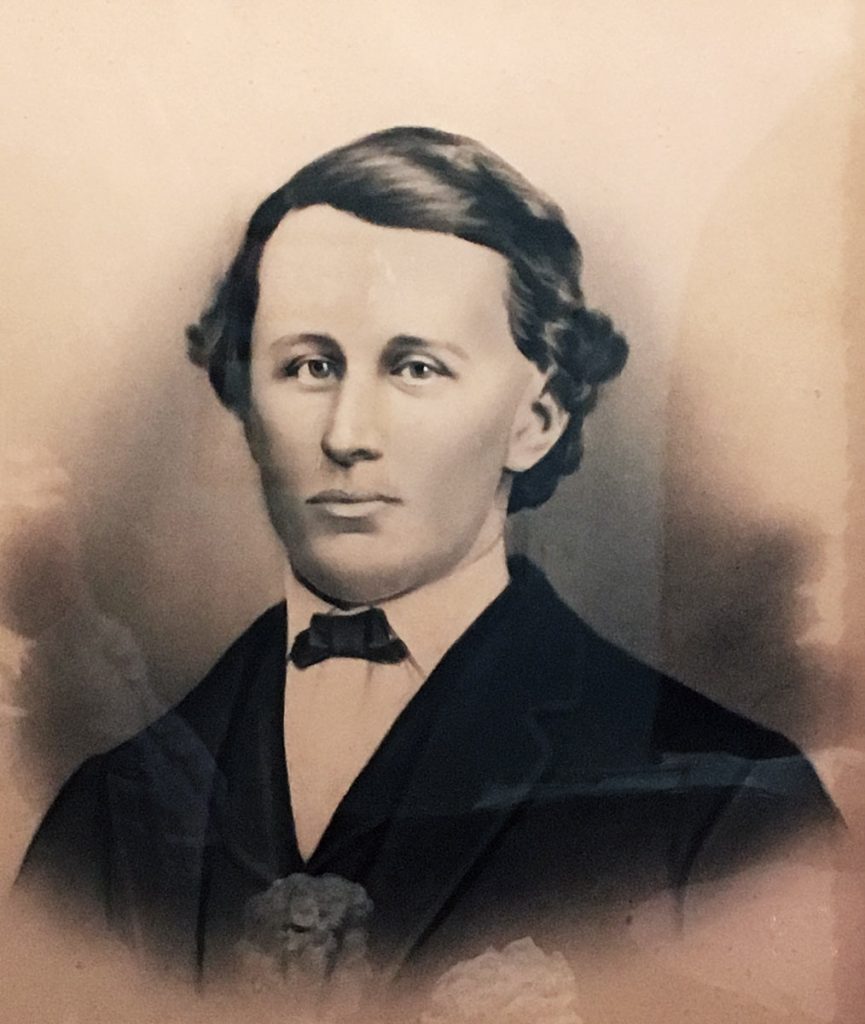

Hiram Hagenbuch, aged 50, and his son, Henry Bruce, had taken ill a few weeks previously. Hiram and Henry Bruce, aged 22, had been helping neighbors clean and repair items that had been in the most recent flood waters of the Susquehanna River. Hiram and his wife, Mary Ann, had no damage to their house or belongings because they had wisely built their new house on a hill about 500 yards from the river’s edge.

When neighbors affected by the flood needed help, Hiram was on their doorstep and had taken Henry Bruce along. He had the next two eldest, (Francis) Eugene and Percy, continue the farm work. Hiram knew the dangers related to cleaning flood items— typhoid fever—a sickness which sometimes ended in debilitation or even death. But, he was known for his friendly and helpful nature so he had volunteered to help, along with Henry Bruce.

Upon being called to the house the week before, the doctor had immediately diagnosed typhoid in both father and son. It was a grave case that was escalating quickly into unconsciousness, the “typhoid state.” Henry Bruce was bedridden in his small second floor bedroom. Hiram was in the large bedroom shared with wife, Mary Ann. Mary Ann acted as nurse to her husband and son, while daughter, Kathryn “Katie”, did the housekeeping and took care of the younger children: Israel, Julia, Harry, Clarence, Franklin, and the baby, Luther. Julia and Israel were also a big help. Israel made sure the other boys were busy and stayed out of the way. Julia not only helped her mother with the two sick ones, but also helped with the baby.

During the past week, family members had stopped in to visit the sick father and son. They had brought prepared foods since Mary Ann was kept busy nursing, and they offered caring words and support. “They” included Hiram’s sister and brother-in-law who lived in Milton, Mary and Tilman Foust; Hiram’s brother, Joseph; Mary Ann’s brother and sister-in-law from Pottsgrove, Benjamin and Elizabeth Lindner; and Mary Ann’s sister, Jane Coleman who was now staying with the family to help.

As the day wore on, Henry Bruce’s breathing became shallower. Mary Ann increased the vigilance beside her son but would periodically move to her bedroom to check on Hiram. She kept cold compresses on their foreheads in hopes that the fevers would break, but the recent visit of the doctor gave no hope. The care of Henry Bruce was turned over to Julia who was only thirteen years old. She was already showing skills and an innate nurturing personality which would lead her in later life to the nursing field. Sitting with Hiram, her Bible open in her lap, Mary Ann read aloud, especially from the Psalms, and prayed quietly. Her sister, Jane Coleman, sat with her. They were already dressed in the black colors of mourning.

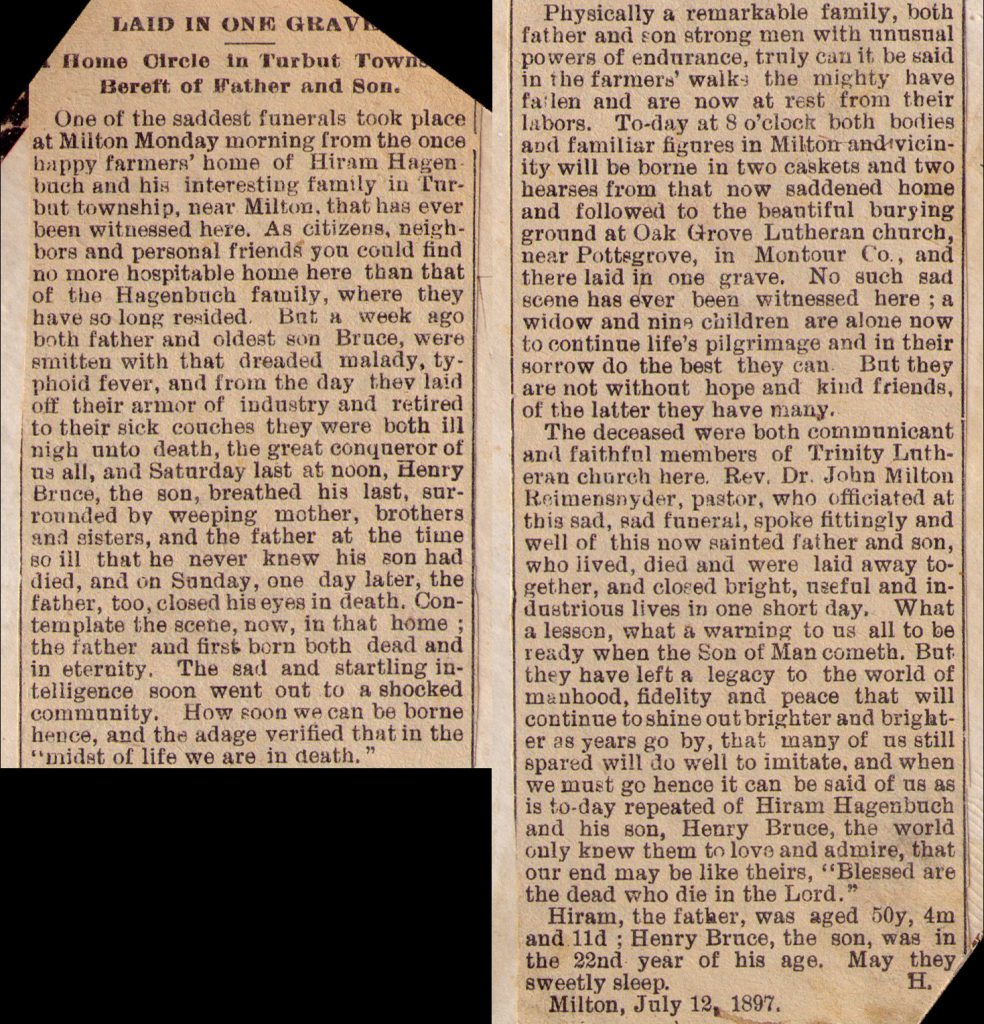

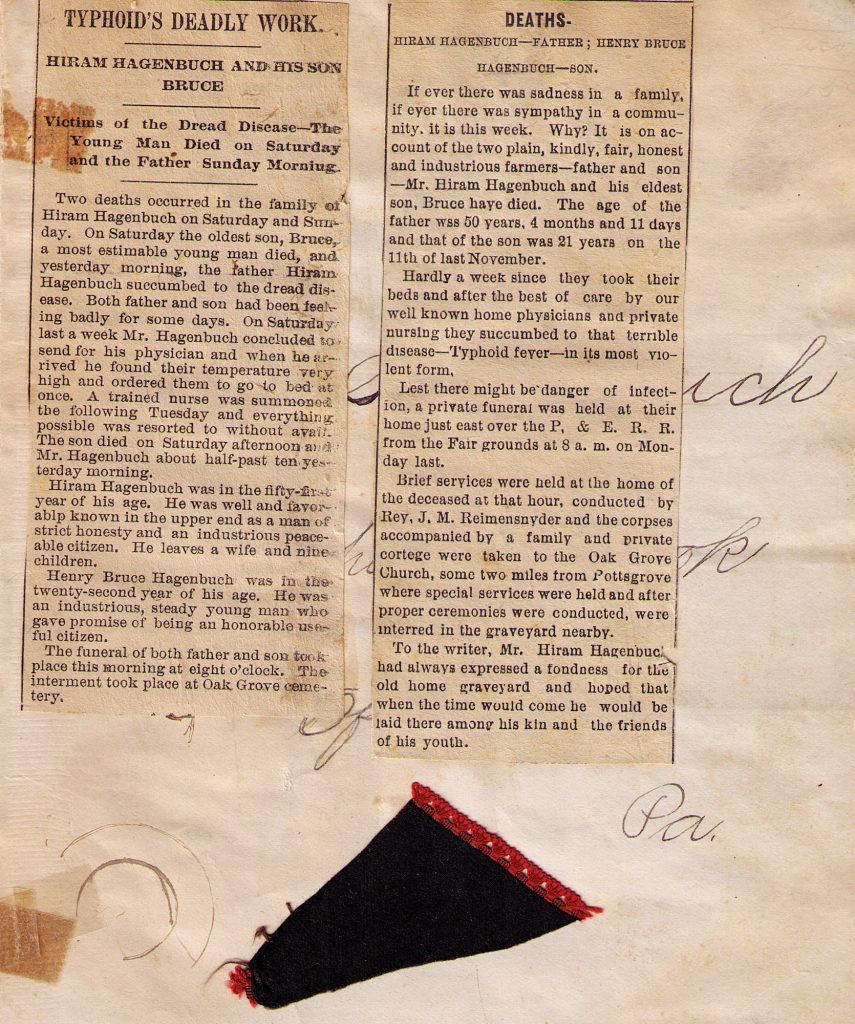

Obituaries for Hiram and Henry Bruce Hagenbuch, 1897. A piece of the casket lining may be displayed here as well.

As midnight approached, Julia called for her mother. Mary Ann rushed to Henry Bruce’s room as he breathed his last, quietly and effortlessly. Mary Ann pulled the sheet over him, put her arm around the sobbing Julia and shut the door. Julia met sister Katie in the hallway, as the mother went back to the vigil beside her husband. The older boys came from the third floor bedrooms. They had heard the commotion with their sisters as they moved to the kitchen. It was a sleepless night for most of the household.

Early in the morning of the next day, July 11, Hiram breathed his last. This was the age of stoicism and although wife Mary Ann found it difficult to contain her grief, she set her mouth tight, covered Hiram with the sheet, walked from the room helped by her sister, closed the bedroom door, and went down the hallway to look once more on her dead son, Henry Bruce. Julia had removed the sheet from his face and was sitting beside him, tear stains on her cheeks, as she looked up at her mother. At this sight, Mary Ann left out a sob, patted Julia on the shoulder, and asked her to “get Katie, and the other children, and meet us downstairs in the parlor. Father has gone to heaven.”

Julia did as she was told and the scene was out of some Victorian painting—a family gathered in grief. Israel was sent out to the barn to bring in Eugene and Percy, who were already at work with the animals. As they entered the kitchen back door, their mother met them with the news. They were the first two of the children to view the dead body of their father. Then they hitched the horse to the carriage to return with the doctor and undertaker. Aunt Jane Coleman, holding baby Luther, ushered the other children to the death beds – first of their father and then of their oldest brother. Although hushed throughout the house, there was activity as the doctor and undertaker arrived, the children were fed their breakfast in silence, and the family sequestered themselves in the parlor and the tower room.

The doctor pronounced Hiram and Henry Bruce dead and the undertaker talked to Mary Ann about the preparation of the bodies. Oldest son Eugene took over the bulk of funeral arrangements with advice from his mother. Although he had just turned 20 three weeks before, he was a capable young man and would continue with the tasks related to the managing of the farm and other businesses in which Hiram was involved.

However, within a few months as the mortgage on the house was due, payments were difficult to make. With the funeral arrangements and the loss of the patriarch’s guidance and skills along with the grief from losing a husband/father and son/brother, it was difficult to remain economically sound. By the next year, the house on the hill went to sheriff’s sale and passed to Mr. Everitt who held the mortgage on the house and whose farm the family had been managing.

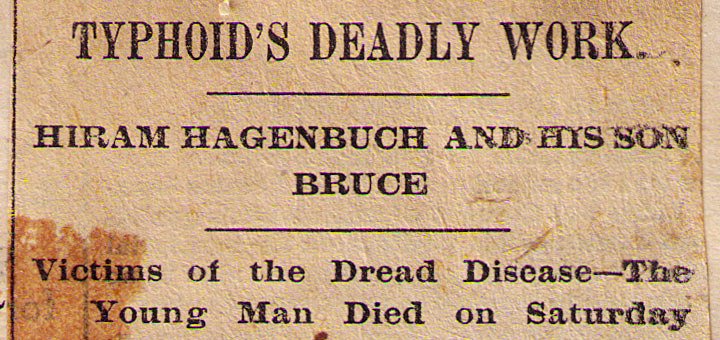

It was a sad state of affairs for a once thriving family, and the populace read about the grievous situation in the local newspaper a few days after the deaths.