The Christmas Putz

Several days ago, my wife Linda and I attended a special showing of nativities at a church near Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. Over 500 nativity scenes or creches were displayed. Many were traditional and made of papier-mâché, molded, or wooden figures of the child Christ in the manger, Mary and Joseph, angels, shepherds, the three kings, and a host of animals set in a stable.

Some of these traditional nativities had just a few figures, some were elaborate with dozens of figures. Nontraditional ones featured figures made from every imaginable material (yarn, cut nails, gourds) and various characters representing the holy family and the visitors (Charlie Brown figures, American Indians, and even rubber ducks!).

Being a historian and traditionalist I thought back to our ancestral family and what they might have known about nativity scenes in the 18th and 19th centuries. Would they have had a carved set of figures or was the idea of a creche completely foreign to them?

Church history tells us that Saint Francis of Assisi was the first to put together a nativity scene in 1223 at Greccio, Italy. Saint Francis used real people in a cave near the town. He did this as a teaching tool and to get the local folks to “put Christ back into Christmas” as he was fearful that the celebration was becoming too secular.

Within a hundred years or so most churches in Italy had nativity scenes, now made of wood, papier-mâché, or other materials in the churches throughout the Advent season. The country of Germany especially took up the tradition and elaborate nativities are found today in churches throughout Germany, Switzerland, Poland, and other countries with Germanic backgrounds.

Christmas Putz on display at New Bethel Church, not far from the Hagenbuch homestead. Credit: Jon Bond

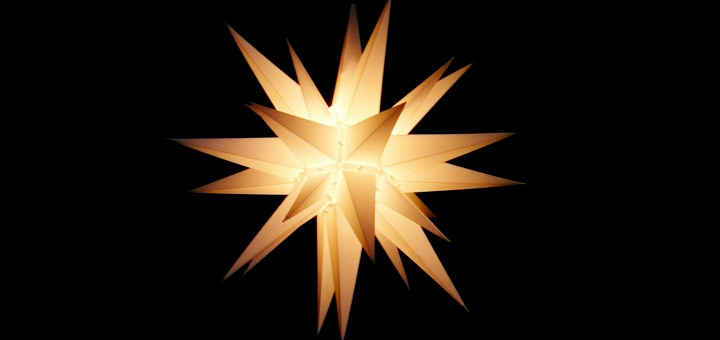

The first recorded instance of a nativity scene in Pennsylvania was in the town of Bethlehem founded by the Moravians in 1741. The nativity was given the vernacular title of a “putz”; the German word “putzen” meaning to decorate. The Moravians, unlike the Quakers and other Plain Dutch sects, did decorate for Christmas time; not only with the putz or nativity, but also with stars, hence the multi-pointed Moravian star, which is still popular at Christmas time today. (However, the three dimensional multi-pointed Moravian star does not appear on the scene until after 1830.)

It is difficult to say if Andreas and his family would have known much about the putz. However, if they were being made and set up for Christmas by the Moravians in Bethlehem sometime after 1741, there is a very good chance that they certainly were familiar with the Christmas Putz. Andreas is known to have had business connections, relatives and friends in the area of Bethlehem; his son Henry had the Cross Keys Tavern in Allentown. Knowing from sources that the early Lutheran Hagenbuchs were deeply religious, as were the Moravians, it is supposed that Andreas and his family were aware of the Moravians, especially as the sect began to move throughout Pennsylvania to evangelize.

We can go off on a tangent here as one relates the Moravians and their beliefs to two of the most important names in Pennsylvania Lutheranism during Andreas’s time: Conrad Weiser and Henry Melchoir Muhlenberg. Both of these Lutheran founding fathers had run ins with Moravians as they attempted to wrest the Berks County Lutherans away from the teachings of Martin Luther to the teachings of the Moravian bishop, Count Zinzendort.

The association of Weiser and other religious leaders with Andreas, his immediate family, and third generation descendants needs to be further explored. However, it is probably safe to say that our early ancestors in Berks County knew of the Christmas Putz and, in the mid-1800s before they moved from Berks County, may have even had a putz set up in an area of their home during the Advent season. Many of us descended from Andreas still carry on this religious tradition today.