What Caspar Wistar’s Story Tells Us About Our Own

Today we know substantially more about our common ancestor, Andreas Hagenbuch (b. 1715, d. 1785), than was understood even a decade ago. Below are a few articles that capture some of this knowledge. Yet, there are still many gaps in his story—ones that may never be filled in with certainty due to missing records.

- Andreas Sails Aboard the Charming Nancy

- Rethinking Andreas Hagenbuch’s Children

- Andreas’s Debatable Birthdate

That said, we can better understand Andreas through the stories of his contemporaries. Upon the suggestion of a friend, Chris Witmer, I recently read the book Immigrant and Entrepreneur: The Atlantic World of Caspar Wistar, 1650–1750 by Rosalind Beiler. Initially, my interest in Caspar Wistar came from a piece of land that he owned and was later sold to Andreas Hagenbuch. However, as I went through the book, I realized Wistar’s story informed and connected with our own in several other ways.

Caspar Wistar was born in 1696 in the Palatine near Heidelberg in what is now Germany. He died in 1752 in Pennsylvania. By comparison, Andreas Hagenbuch was born in 1715 in the Duchy of Württemberg near Heilbronn, also in what today is Germany. He died in 1785 in Pennsylvania.

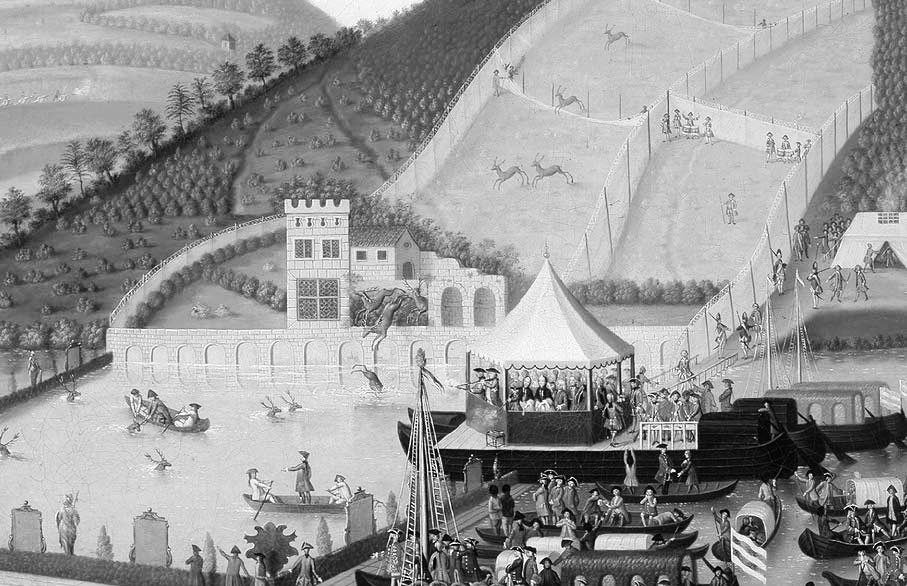

Wistar’s experiences give us a sense of what life was like for our ancestors residing in German states during the early 1700s. Years of war had left many families living in hardship. Resources were constrained, with too many people vying for too little land. This resulted in bureaucratic regulations that limited economic and job opportunities. Wistar’s father held a government position as a forester. Individuals in this job helped to manage resources and organize hunts on lands owned by the ruling Elector Palatine. The goal of a forester was to balance the land use of the Elector against the needs of the people.

We do not know the profession of Andreas Hagenbuch’s father, Hans Michael (b. 1685, d. 1735). However, while reading the duties undertaken by a forester, I was struck by how these connected with the Hagenbuch coat-of-arms and the story of the Buchbaum. It may be that our earliest European ancestors (many generations before Andreas) were foresters who managed resources, built fences and hedgerows, and tended to the animals and trees on the land.

Caspar Wistar was an early German immigrant to Pennsylvania. Later in life, he penned his memoirs in “A Short Report” and explains the process of leaving home. He went by boat down the Rhine River to Rotterdam. Then he sailed to England where he boarded a ship bound for America. Wistar describes how emotionally difficult it was to leave his parents, friends, and other family. As he turned to leave, his mother ran to him and cried, fearing she would never see him again. Although her premonition was correct, Wistar remained in contact with his family, writing letters and even helping some of them immigrate to Pennsylvania.

By comparison, Andreas Hagenbuch’s parents died prior to him leaving home and, perhaps, their death contributed to his decision. His father’s death in 1735 may have provided him with an inheritance to pay for the journey. Additionally, we know that Andreas’ younger brother, Philip Jacob Hagenbuch (b. 1725), traveled to Pennsylvania in 1751 and resided with his older brother for a time. It stands to reason that like the Wistars, the Hagenbuchs wrote letters and corresponded with family across the Atlantic.

Wistar landed in Philadelphia in 1717. He arrived alone and with very little money. This led him to take on a variety of odd jobs, such as hauling ash for a soap-maker. Within a few years, he became apprenticed to a brass button-maker and mastered this craft. His success as a button-maker earned him enough money to marry and begin his entrepreneurial ventures. He speculated in real estate, imported hard-to-find goods like German hunting rifles, became a partner in an iron furnace operation, and started a successful glass works. By the late 1740s, Caspar Wistar was one of the wealthiest, self-made people living in the colonies.

Andreas Hagenbuch arrived in Philadelphia 20 years later in 1737 on the Charming Nancy which was captained by Charles Stedman. The ship was likely carrying goods for Wistar. In a letter to a European business associate, Wistar described Captain Stedman as “my good friend” and entrusted him to transport valuable items to Philadelphia.

Dog-shaped bottle, a schnapshund, from the Wistar Glass Works made during the mid-1700s. Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art

Unlike Caspar Wistar, Andreas already had a wife, Maria Magdalena, and a one-year-old child, Henry. He also had money in his pocket and possibly a few personal connections to rely upon. These factors enabled him to quickly acquire land in early 1738, only a few months after arriving. Similar to Wistar, Andreas had ventures in a number of industries including agriculture, textiles, distilling, and land speculation. He even acquired a piece of property in Northampton County, Pennsylvania that had once been part of a larger tract owned by Caspar Wistar. At this location, his son, Christian Hagenbuch (b. 1747), would build a distillery.

Yet, Andreas Hagenbuch never attained Caspar Wistar’s level of success. One reason likely had to do with networking. Wistar, quite shrewdly, converted to the Quaker faith after arriving in Pennsylvania, while Hagenbuch remained a Lutheran. This opened up many more opportunities for Wistar and helped him to connect with powerful Quakers, such as the Penns. Wistar then married Catherine Jansen, a Quaker whose father was a large landholder and justice of the peace for Philadelphia County.

Another reason is that the best land and resources—closest to the port city of Philadelphia—had been settled in the early 1700s. By 1737 when Andreas arrived, good land had grown more expensive and new immigrants were forced to settle in the wilderness, far away from major cities. Though they did well for themselves, the Hagenbuchs were more isolated and not as well connected as the Wistars.

Despite this, there is evidence that the Hagenbuchs and the Wistars were themselves linked through marriage. In “A Short Report” Caspar Wistar mentions the name of his first cousin, David Deshler, who was the son of his aunt, Maria Helena (Wistar) Deshler (b. 1684). David and his brother, Adam (b. 1713), immigrated to Pennsylvania, with Adam settling in what would become Lehigh County. It appears that Adam was the grandfather of Jacob Deshler (b. 1781). Jacob married Elizabeth Hagenbuch (b. 1788), a granddaughter of Andreas Hagenbuch.

Caspar Wistar’s unique story provides another lens for understanding how our ancestors lived in Europe and their early experiences in Pennsylvania. His life connects with our Hagenbuch family through land purchases, the voyages of Captain Stedman, and even marriage. In other words, Wistar’s story is also a part of our own.

It is always amazing what you two discover about the Hagenbuch family. It baffles me that you can find information from that long ago. Keep up the good work, it’s always good to read about the ancestors and what their lives entailed. Nothing boring here!!!!! Thanks again Andrew and Mark.