Butchering Day Memories from the Farm, Part 1

Last Tuesday was Fastnacht Day here in our part of Pennsylvania. In our Montour County household we called it Doughnut Day. It wasn’t until I moved to York County thirty years ago that I consistently heard the term “fastnacht” meaning the doughnut cooked in oil the day before Lent begins.

Of course, on the farm, Mom (Irene “Faus” Hagenbuch) did not use any oil. It was lard; and lard that had only just been rendered a few weeks before when we butchered. Similar to the Biblical phrase “to every thing there is a season”, there was an order of tasks on the farm starting in January with butchering. January was cold, the pork and all its related items kept fresh, the hot kettles and water in the scalding trough was welcoming, and the men butchering didn’t work up a sweat!

Someplace, among all my old family photos, is one of me when I was probably about 7 years old. I am standing in back of our house in the snow dressed in those 1950s clothes, a bandanna wrapped around my mouth and face, and a steaming butchering kettle in front of me. I spent several hours before I wrote this looking for that photo. No luck.

However, I did some research on butchering hogs and found some excellent articles written by two columnists: Robert Wood and Richard Shaner. Their articles on butchering appear in “Berks-Mont”, an online newspaper. Mr. Wood and Mr. Shaner trace the history of butchering in the Berks County region, where our early Hagenbuch ancestors lived.

Much of their description of 19th century butchering day certainly is no different than what I remember as a boy – killing the hog and sticking it to let it bleed out, scalding and scraping, hanging and splitting the carcass, and then all the jobs that followed. These included slicing the different cuts of meat, cutting lard, and cooking the different organ meats down to make puddin’ as well as scrapple.

I remember well one of the men of the butchering party would shoot the pigs with a .22, then slit the throat to bleed it out. Now, the real work began because the several hundred pound deceased porker was dragged to the huge wooden vat of hot water and lifted into it. I believe this was usually done by the tractor with a manure loader. Several chains underneath the carcass allowed the men to roll the pig around which loosened the body hair. Pig scrapers, wooden handles with round metal disks attached, appeared and everyone who could began scraping hair. Roll and scrape, roll and scrape until all visible hair from every part of the body was removed.

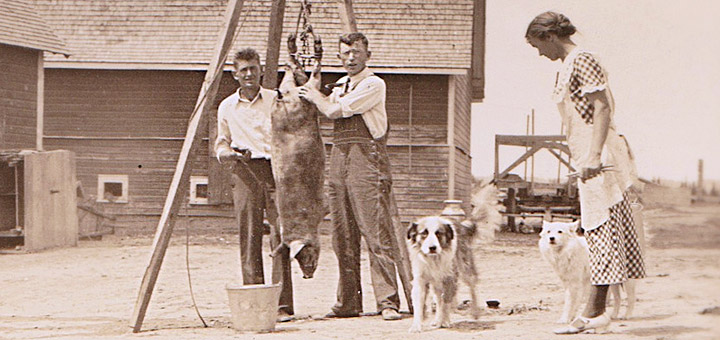

Most of the actual butchering on our farm near Limestoneville was done in what we called the shanty, a long unheated room attached to our kitchen. There were two or more long butcher tables in the shanty to cut up the meat. The end of the shanty had an open fireplace with a crane where a kettle could be hung. But, there were also one or two boiling kettles outside set up on the snow covered grass with open fires underneath. Two large wooden tripods, about 8 feet tall, stood in the yard to hang the hog carcasses.

As a boy we did not use the term scrapple, we called it ponhaws (or panhaas). I’ve talked to several Pennsylvania Germans (Dutchies!) about where this word derives from and none of us are sure. Is it a combination of the word “pan” (since you use scrapple pans or bread pans to cool it in) and the German word “haus” (house); or does it have something to do with pan fried rabbit, the German word for rabbit being “hase”? The story here is that our Pennsylvania German ancestors jested with their English neighbors when they pan fried the scrapple and told them it was rabbit, not wanting to admit what had been cooked to make the “ponhaws”!

Scrapple making is an art. The word comes from using all the scraps left over when butchering. As they say: “Everything but the oink”! It includes organ meats such as kidneys and liver, along with jowls, snout, pieces of fat, scraps of better cuts of meat, and unmentionable scraps!

It is all cooked in a huge kettle of water. Once it is cooked soft, the meat – now called “puddin” – is dipped out with a strainer and put in pans to cool. This is “eatin’ high off the hog” and as a boy we would put puddin’ on pancakes, waffles, or bread. The broth that is left is then cooked down with added cornmeal and spices. Every butcher had his own recipe.

My father’s (Homer S. Hagenbuch) first cousin on his mother’s side, Myron Cromis, was an expert at scrapple: just the right amount of pepper, salt, brown sugar, and other spices (usually a secret) were thrown in as the mixture boiled away and thickened. Eventually, it is thick enough to put in scrapple pans. When cool it is sliced and fried (the best way is in a bit of lard!).

Scrapple, or ponhaws, was a breakfast food served with fried mush all smothered in King syrup, not maple syrup. We called King syrup “molasses”, and it came in a red can with a lion on it. The fried mush was boiled cornmeal set up in a loaf pan, then sliced and fried. A few times each year I still happily repeat the breakfasts of scrapple, fried mush, “dippy” eggs, pancakes, and King syrup; a repeat of childhood “good eats”!

Next week, we’ll continue with the second installment of Butchering Day.