A Boy with a Movie Camera

Moving pictures are a powerful way to capture and preserve history. In 1929, the Ukrainian filmmaker Dziga Vertov released his silent film, Man with a Movie Camera. It was largely dismissed due to its lack of a narrative plot and use of an experimental documentary style. Today, however, Vertov’s movie is considered an important work of cinema. Many of the techniques he refined or invented—including split screen, jump cuts, and stop motion animation—inspired later filmmakers.

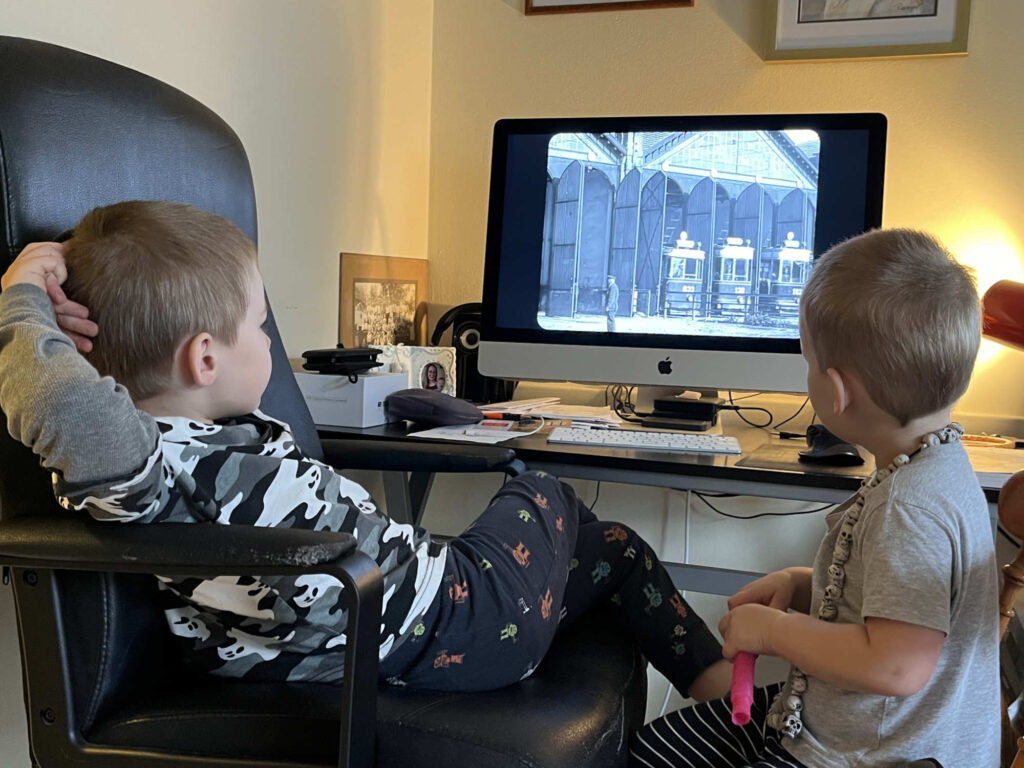

I first saw portions of Man with a Movie Camera in college. At the time, I didn’t think much of the film. Yet, after recently watching a restored version of the film with a soundtrack by the Cinematic Orchestra, I feel differently about the movie. And, it’s not just me. My young sons, William and Henry, watched part of the film with me and found it captivating too. (Man with a Movie Camera is provided below and begins at about 8 minutes in, when the music and images become more interesting to watch.)

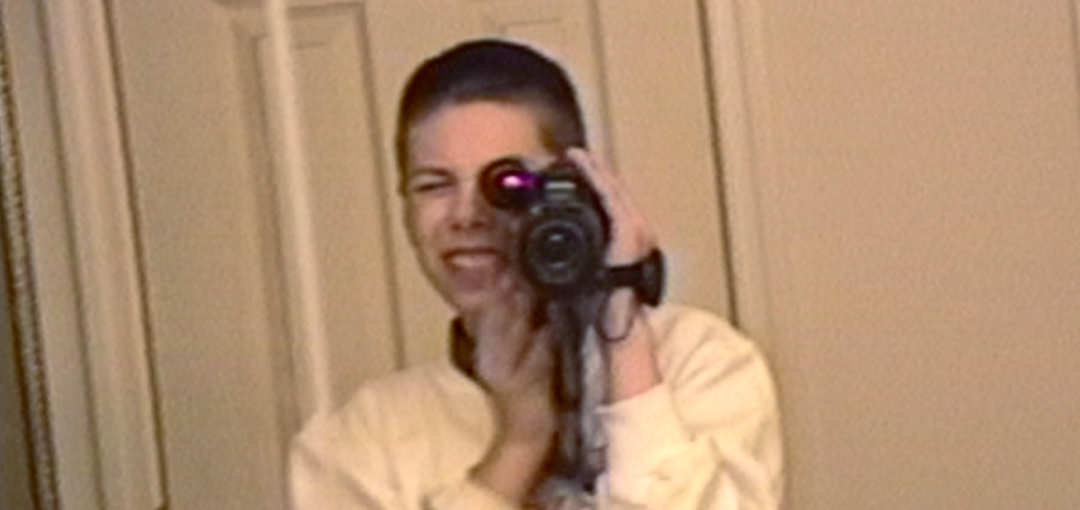

My interest in movies—a term coined from the phrase “moving pictures” around 1908—started in December of 1992 when my parents purchased a Sony 8mm video camera. They thought it would be good to have for an upcoming family road trip they were planning. I was 11 years old and was immediately drawn to the camera. Looking back, I can see that this event really ignited my passion for media and technology. Not only did I want to use the camera, I also wanted to learn how it worked and to see how far I could push what was possible with it, similar to Vertov.

As explained in a previous piece, I have been digitizing and archiving family video tapes. My goal is to preserve them for future generations, just as we do with stories, letters, books, and photographs. Video tape is a fragile medium. Magnetic tapes may only last a few decades. From my own experience, I am seeing first hand how tapes from the early 1990s are decaying and becoming unreadable.

Thankfully, I have had more successes than failures. About a month ago, I was able to play, capture, and preserve the first few tapes ever shot on my family’s 8mm video camera. Amateur home movies don’t have a reputation for being must-see cinema. Yet, much to my surprise, the tapes were a wonderful treat to watch. Footage that hadn’t been seen in over 30 years provided a glimpse of a time that was otherwise only a memory. The movies sparked a flurry of text messages and phone conversations within our family, as we reminisced about relatives, holiday gatherings, and past home decor.

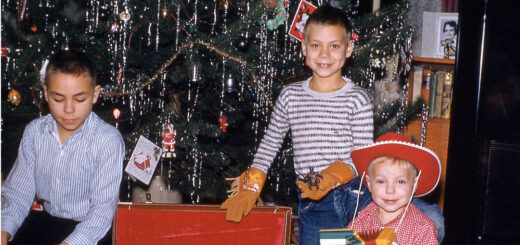

But something else struck me—how the eyes of a child provided a fascinating lens through which to observe the world. Once handed the camera, I used it without any preconceptions of how or what I should shoot. I started experimenting and documenting my surroundings. I captured walk-throughs of the family home and recorded our cat, Pepper. While investigating the Christmas tree, I inadvertently taped conversations between my parents as they decompress after work. Thirty years ago, these videos must have been boring to watch. But today they are terrific documents of a time and place that no longer exists as it was. (Watch the following clip to see Christmas lunch at Homer and Irene (Faus) Hagenbuch’s from 1992.)

There are recordings of family events too, gatherings of Hagenbuchs and Gutshalls (my mother’s side) during the holidays. Faces, foods, decorations, and presents can all be observed through moving pictures and audio. How much each of us has changed—or not—through the decades! How wonderful it is to see those who are no longer with us laughing and talking again.

Again, what would have seemed boring at the time is now the focus of our fascination. In one segment, I placed the camera on a tripod and recorded Christmas at my Hagenbuch grandparents. In another, I captured a conversion between me and my maternal grandfather, Roy A. Gutshall Jr. (b. 1920), where I explained to him about how the movie camera worked. Needless to say, these video tapes are an irreplaceable treasure filled with more than could be held by a single snapshot.

My interest in recording family gatherings and goings-on at home quickly waned. While my parents used it to chronicle school events and concerts, I had ambitions of real filmmaking. Soon, my sisters, our cousins, our friends, and even the family cat, were creating short, narrative movies about detectives, science fiction space stations, and wild misadventures. Many were recorded in my parents’ basement, which we converted into a studio complete with sets and costumes. These tapes are fun to watch too, although they have less to offer as genealogical documents.

Stepping back, I now see how important a child’s view of the world can be to preserving the past. I also have come to realize just how little of the present I capture on video. While I take thousands of photographs every year, I rarely use video. Why is that? One reason may be that video requires a bit more effort to shoot. Another could be that a phone, which most of use to take photos, feels more like a point-and-shoot camera than a video camera. Whatever the reason, I feel like I should be taking more home movies, especially now that I have children.

With this idea in mind, I have purchased my eldest son, William, a basic video camera for his birthday. Yes, they still make these! Even a low-end, $60 camera has abilities that a $1,000 model lacked decades ago. My hope is that like Vertov and me, William will become interested in capturing his world through moving pictures. Whether the recordings are high art or amateur in quality is of no consequence. What matters is that his footage will preserve a moment in our family’s history—something that we will value in the decades ahead.