Andreas Hagenbuch’s Continental Money

When Andreas Hagenbuch died in 1785, the inventory of his estate was valued at over 1100 pounds or around $200,000 today. This inventory included personal effects, as well as cash and bonds. One item stands out from the rest because it was assessed as having no value. Oddly enough, this item was “banknotes for 3500 dollars continental money.”

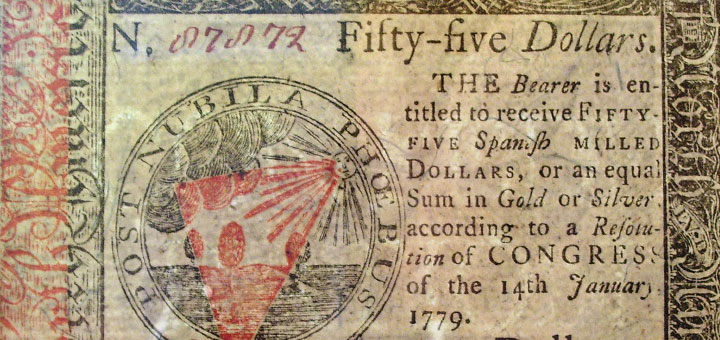

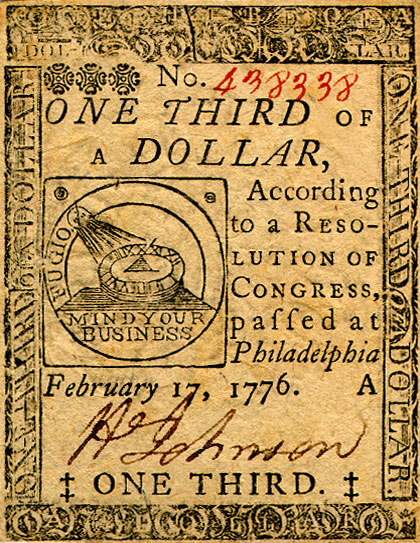

To understand why Andreas’s Continental dollars were seen as worthless, it is necessary to understand their history. Continental money, denominated in dollars, was first issued by the Continental Congress at the beginning of the Revolutionary War in 1775. The new currency was established in order to divorce America’s thirteen colonies from the British pound.

Developing a new, reliable currency isn’t an easy task, and right from the start the Continental dollar ran into trouble. Over the next ten years, its value quickly depreciated until it nearly became worthless. This led to the popular phrase “not worth a Continental.”

There are a number of theories explaining the failure of the Continental dollar. Early on, it was believed that a paper currency not backed by gold would ultimately fail. While a possibility, it is necessary to point out that the current United States dollar hasn’t been backed by gold for decades, yet still remains one of the world’s most stable currencies.

Another more likely theory is that the Continental Congress simply authorized the printing of too much money, which led to runaway inflation. This was compounded by the effects of counterfeiters who were able to easily copy the design of the Continental dollar and print their own money. In fact, some of the counterfeited money was even produced by the British, who hoped a glut of fake currency would destabilize the colonial economy and swing the war in their favor.

Whatever the root cause, Continental money was nearly worthless by the end of the Revolutionary War in 1783. This explains why it was given no value in the inventory of Andreas Hagenbuch’s estate. It was not until the 1790s, after the establishment of the United States Constitution, that the Continental dollar was finally taken out of circulation. According to The Early Paper Money of America by Eric Newman, after the creation of the United States dollar, Continentals could be exchanged for treasury bonds at a rate of 100 to 1. A person received, quite literally, a penny for every Continental dollar!

This raises the question of why Andreas Hagenbuch held 3500 dollars of worthless Continental money when he died. One potential answer is that he directly supported the Revolutionary War and had received payment from the Continental Congress. It is known that the Hagenbuchs were producing linen, leather, and brandy at their homestead in Albany Township, Berks County, Pennsylvania. All of these goods were needed by the Continental Army during the war.

Another idea is that Andreas received the money from locals who had been paid by the Continental Congress. It is known that soldiers in the Continental Army, when paid at all, were given Continentals to compensate them for their service. As a result, they would have tried to use this money to buy goods and services. Andreas Hagenbuch likely came in contact with a number of servicemen, even in Albany Township. His sons Henry, Michael, Christian, and John all served during the Revolutionary War.

Realizing the worthlessness of Continental dollars, it is a wonder that Andreas Hagenbuch ever accepted them as payment–or is it? With German roots and four sons serving in the war, it is likely that Andreas strongly supported the efforts of the colonies to end British rule. Accepting the currency was simply another manifestation of his patriotism.

Therein lies the most nuanced understanding of the “banknotes for 3500 dollars continental money.” Yes, the currency had no value. Every person who accepted Continental money for goods or services had, in essence, given these away for free.

Yet, maybe, the act of accepting the money meant more than its simple economic value. To hold a Continental dollar, in effect, showed that one had donated something to support the cause of the American Revolution. In that sense, Andreas Hagenbuch might have seen the 3500 Continental dollars not as a negative loss but as positive proof of his contributions towards building a new country.

I have a walking stick with a brass knob etched with the name ‘A Hagenbuch’…not listed in his estate. Got this from my fathers estate. How did it make it to Northampton, Pa,?? Got any ideas?

Hi Charles. Nice to hear from you! Sounds like a great find. I’d love to see a picture of it. This type of cane or walking stick didn’t become popular until the 1800s, so I do not believe this is Andreas Hagenbuch’s (b. 1715). However, there are other possibilities. I think one strong one is Andrew J. Hagenbuch (b. 1852). He was born in Northampton County and his father, Joseph (b. 1811), is buried in Bath, Northampton Co. Feel free to send me an email through the site so we can discuss further: https://www.hagenbuch.org/contact-us

I’ll post a pic as soon as I can. I think that must be the guy. I live in Bath. It would make sense that my dad picked this up around here as he grew up in Nazareth. Stay tuned for pic and Merry Christmas.