Remembering James H. Hagenbuch: a Brother’s Closure

James H. Hagenbuch (b. 1922) died on June 7, 1944, after engaging German soldiers just south of Dead Man’s Corner in Normandy, France. James served in Company A (Able Company) of the 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment (PIR). Also in Able Company was Donald “Don” Burgett, who wrote about James in his 1967 book Currahee!: A Screaming Eagle at Normandy. Read Part 1, Part 2, and Part 3 in this article series.

James had a younger brother, Joseph (b. 1924), who served in the U.S. Army during World War II and survived. After the war, Joseph went on with life and became a portrait artist. Yet, he often thought of his brother and wondered what circumstances led to James being killed in action. Finally, in 2004 a chance encounter with Donald Burgett brought Joseph and his family closure.

Burgett recounted this moment in a post on his personal website, which sadly no longer exists. The following is a transcription of that post with a few edits for grammar and clarity.

A Brother Sends Closure

By Donald R. Burgett

I had an appointment for an examination in the VA Hospital in Ann Arbor, Michigan. My appointment wasn’t until the following week. But since I had business in that area, I somehow had a strong feeling that if I stopped in about mid-day and if their schedule was not too full, I just might have my exam early. As I dressed, I reached for a jacket. The weather wasn’t that cold but a light jacket would be comfortable.

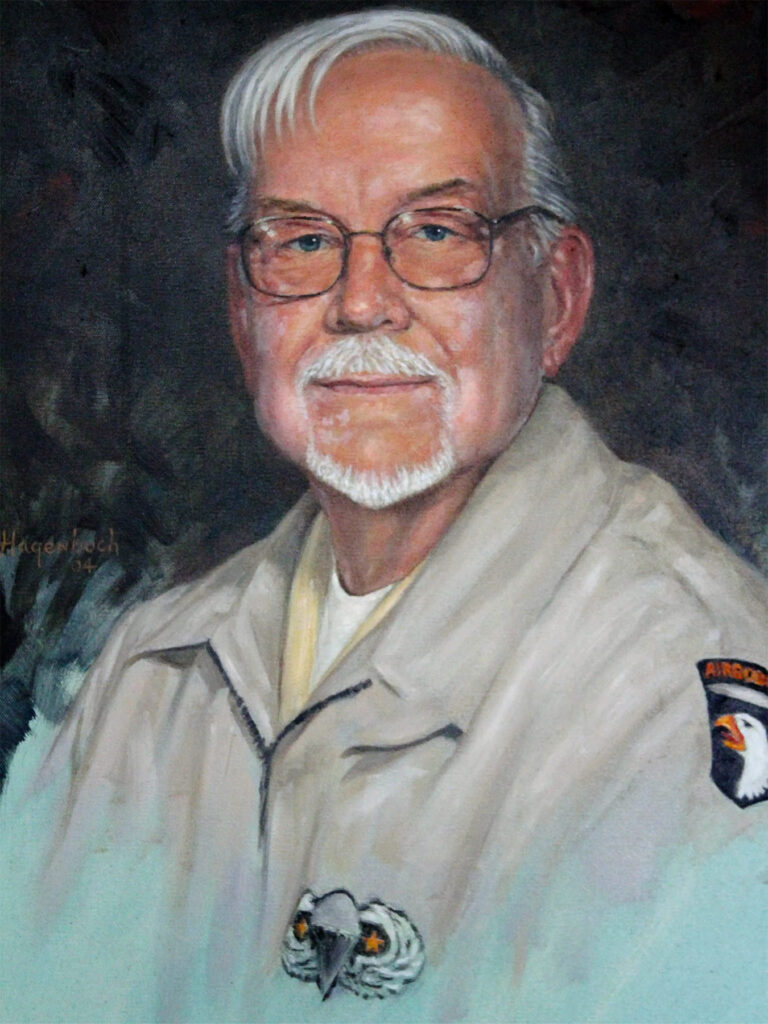

First, I chose a light tan jacket. Then, a thought came to me—as long as I was going to the VA Hospital filled with vets, I may as well wear and show off my fairly new jacket with a large “Screaming Eagles 101st” patch on the back and the regimental “Paradice” patch of the 506 Parachute Regiment on the front. The well-known Screaming Eagle shoulder patch was boldly positioned on the left shoulder. The “Paradice” patch depicted a pair of dice showing the numbers five and six. In between these two numbers was a large black “O” piercing the two dice. All were framed from behind with a large silvery parachute and a screaming eagle in a piercing dive. [Another patch on the front was the “Currahee Insignia.”] It showed the green mountain, Mt. Currahee, the “Currahee!” battle cry of the 506th Parachute Regiment 101st Airborne Division, a jagged lightning bolt, and six parachutes. [It was] a beautifully appointed jacket proudly displayed with sewn on patches and insignias of my former regiments and division of WWII.

I drove from Howell, Michigan to Ann Arbor, completed my business early, and stopped in at the VA Hospital. After parking in the multi-level garage, I made my way to the large main hall where “stations,” as they are called, are located in the perimeter outer walls of the hall. When one is scheduled for an appointment, he is assigned to a station to appear at. Most of these stations have lines of veterans from three or four men to as many as twenty, all patiently awaiting a turn to be interviewed. Then, they sit to await a nurse to call their name to be ushered into a medical room where the exam begins.

Men stood in long lines at the stations patiently waiting their turns. I located my assigned station and couldn’t believe what I saw—one man stood alone. [There was] no long line, no line at all, just one man quietly standing. It was highly unusual that there was no line. Never before have I ever been in a VA Hospital and not had to stand in line. Walking casually to the station, I took my place behind the waiting man. I knew he sensed my presence, but he made no sign of it, not even a shrug of the shoulders or a fast glimpse behind.

A few minutes went by that always seems much longer when waiting in line. Finally the man in front turned around, looked at me, then without acknowledging me in any way, he turned back toward the front. After a couple more minutes, he turned again, this time looking a little longer at my jacket with its patches showing my pride in the unit I served in during WWII. A couple of more minutes [later], the man turned a third time, looked at my jacket, and then at me.

“I had a brother that was in the 506,” he said, referring to the 506 patch on the left front of my jacket.

“What company?” I asked.

“I forgot,” the man replied.

“What was his name?” I questioned, feeling that of the many hundreds of men in a regiment there was little chance I would know him.

“Hagenbuch,” came the reply, with the German soft blowing pronunciation of the “ch” as in the composer, Bach.

I was startled. The sudden jerk of my head and my surprised look caught the attention of a man not in line, but sitting within three feet from me in a waiting chair for his turn to be called.

“Jim?” I asked.

Now it was the man in front to be suddenly and visibly shaken. “You knew my brother?”

“Yes. Jim Hagenbuch was with me when he was killed. I was firing a machine gun at a bunch of Germans running across a road in Normandy, and Jim was loading for me. The Germans got some men across the road and set up machine guns of their own. Three of them returned fire on us. About the third burst of fire, my machine gun jumped to one side, and I heard a ‘plock’ like sound. When I looked, Jim had been hit through the forehead above his left eye. He had been killed instantly.”

The other man was in mild shock, tears welling up in his eyes. A cold chill when through my body. I could feel the hair raise on my arms. I could feel tears coming to my eyes.

[The man] looked at me in disbelief and stated, “I am Joe Hagenbuch. Jim was my older brother. Our family never knew where, when, or how Jim died. For over sixty years, we never knew. All we, the family, ever got was a telegram that stated, ‘We regret to inform you that your son, Jim Hagenbuch, has been killed in the line of duty.’ That is all we ever got. For over sixty years, we have tried everything but could never get any information when, where, or how my brother, Jim, died.”

By this time, tears were running down both Joe’s and my own eyes and cheeks. The man sitting in the chair next to us stared at me with eyes wide open, unblinking. He wore a Marine cap. He never said a word, just stared in disbelief.

I fumbled in a pocket, brought out one of my cards, and introduced myself as a writer of books on paratroops. I told Joe that the story of Jim’s death was in my book, Currahee! I would send him copies of my books. Jim gave me his card with a name, no address or phone number. He wrote his phone number in for me. After arriving back home, I did send the promised books to Joe Hagenbuch the next day.

We talked by phone after Joe had read the books. Joe told me he lived in New Jersey. Then, one day a feeling came to him that he had an aunt he was fond of living in Oak Park, Michigan. He hadn’t seen her in some time and [he thought] he should visit her. Time was passing, they were all getting older, and they should get to see each as family soon.

Following a strong feeling, Joe packed up, traveled to Michigan, stopped at his aunt’s home, and prepared to stay a week or more. While there, he suddenly recalled he had a previous appointment at the VA Hospital, but he could make it here in Michigan instead of waiting to return home.

“Get your appointment,” an inner voice urged, “and get it over with.”

He made an appointment that somehow fell on the same day and time I had stopped in.

My appointment was not for another week. But somehow I had a feeling that since I had business in Ann Arbor, perhaps I could have my exam early and wouldn’t have to make another trip through heavy traffic a week later. At the same time, just as I was leaving home for Ann Arbor, I had that strange feeling to change jackets and wear that one with the patches of my regiment, the 506. I changed jackets.

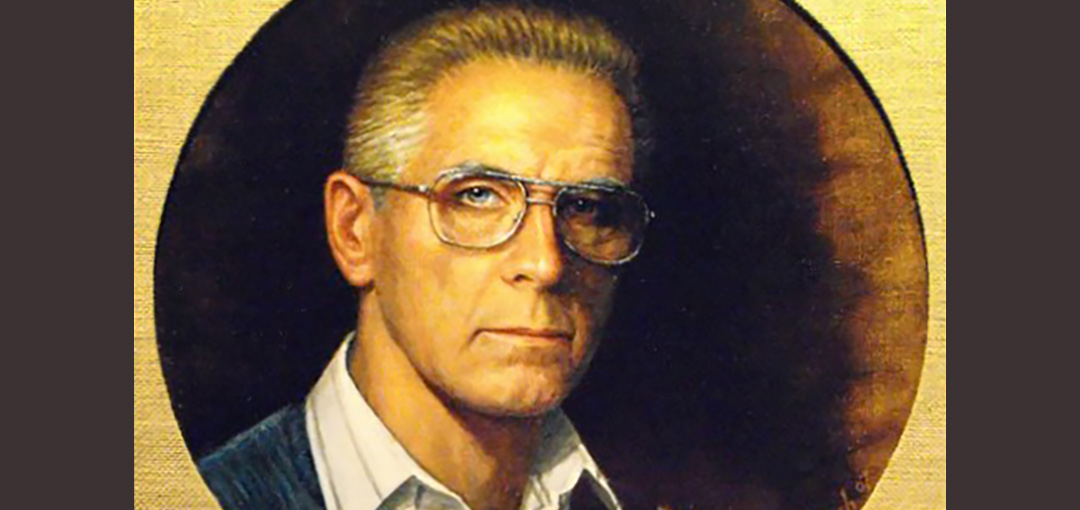

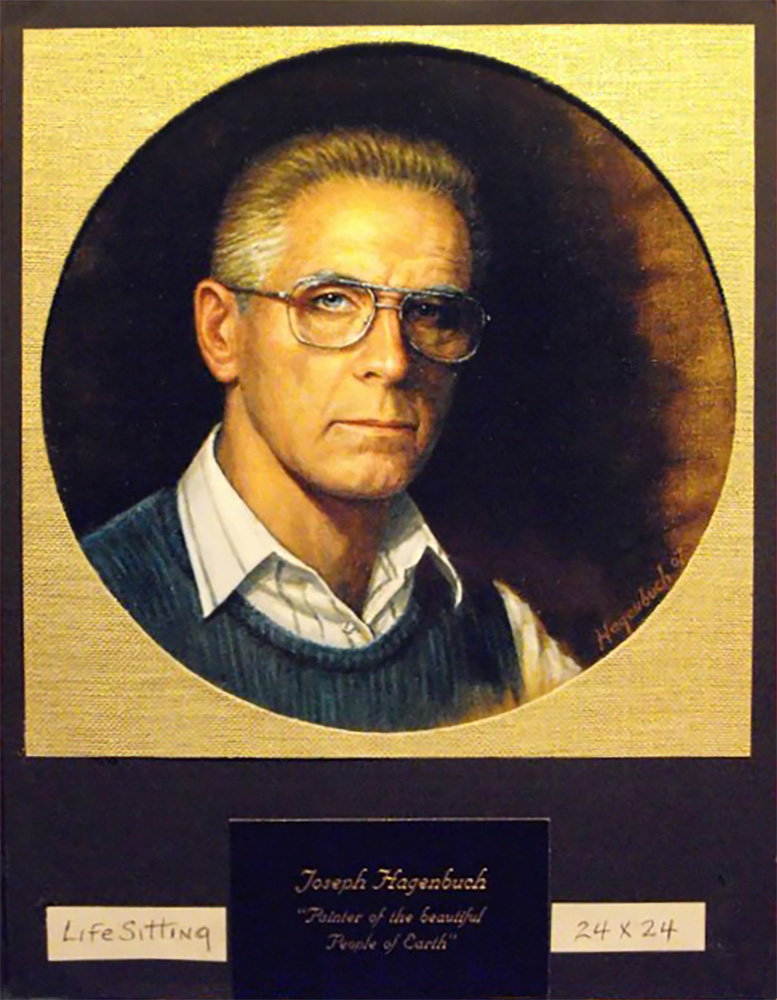

A day or two later I received another phone call from Joe, telling me how excited his entire family was to finally learn the facts of Jim’s death in combat. Joe then told me that he is a portrait painter. He does well enough that he can choose his clients who sit for him and does not include his phone number or address on his cards. He asked if I would allow him to do my portrait. I agreed. We made an appointment. Joe insisted that I wear the same jacket I wore when we first met.

Joe arrived on the day and time agreed upon, and I sat for him to take about thirty photos from all angles and light. About two weeks later, Joe Hagenbuch phoned asking if he could deliver the portrait the next day. I agreed. When Joe drove in the next day, he presented the portrait in a black plastic bag, set it up on the couch, then with a flourish and a “ta-dah,” he pulled the bag up revealing the painting. I was almost in shock.

“What do you think?” he asked.

I replied that it was like looking in a mirror. Joe Hagenbuch’s painting of me is beautiful workmanship that a camera can never capture. The painting came from the heart, capturing an expression of eyes that no mechanical camera can ever produce. My wife and I just stared wordless. Joe stood smiling, eyes shining. He then told me the painting was for the final closure I had brought to his entire family.

Joe then looked very solemn and spoke directly to me. “Don, I am not a really religious man. But I feel that my brother arranged this whole thing. I wasn’t supposed to be in Michigan. I wasn’t supposed to have an appointment at the VA in Ann Arbor. You weren’t supposed to be there but came in on your own following an urge. All the others connected with that battle of Dead Man’s Corner are long passed on. You are the only one left alive that knows when, where, and how my brother, Jim Hagenbuch, died. My brother arranged it for us to get together so that my family, after sixty-one years, now has closure.”

Little else is known about Joseph Hagenbuch. However, research shows that he may have moved to Oak Park, Michigan sometime after meeting Donald Burgett. There he was part of the South Oakland Art Association. Near the end of his life, he appears to have moved to Miramar, Florida. Joseph Hagenbuch died on December 5, 2016 and is buried in the South Florida National Cemetery.

The fifth part in this article series will explore some final thoughts on the lives of James and Joseph Hagenbuch and consider what their story means to us today. To be continued…

Many thanks to Judy Cahoon Egan for finding, printing, and saving Donald Burgett’s post about meeting Joseph Hagenbuch. Without her efforts, no record of the encounter would exist today.

What an amazing story ! I had chills but also tears thinking of how that meeting came to be ! Good one , Mark and Andrew ! Thank you for all the time you spend on these articles .

Thanks Andrew and Mark for this continuing story. There are times that I have also felt the pull of someone helping me to make decisions. I truly believe there are powers that guide our lives. Looking forward to the next chapter…..thanks again.

Thank you Andrew and Mark for bringing this story to light at our 2022 Hagenbuch Reunion. My husband and I were truly amazed and we are reading all the connecting articles.

I love the words of Barbara Huffman and Dave Hagenbuch, I couldn’t say it any better than them.

Thank you,

Norma Kay

I love this story. I started reading about your 300 mile trip in your May 21, 2024 article which led me to the love story of James Hagenbuch and Jeanne Kieser. One story led to another, his uniform and helmet, grave and this is the 4th story I have read about James Hagenbuch. I see there are a couple other stories about him I will also read. Coincidentally, I am finding out his story the day before he was killed in action 80 years ago. I saw in this article when Joe passed, but didn’t know what happened to Donald Burgett, so I looked online for his obituary and found he passed about 4 months after Joe on March 23, 2017. The picture used in Donald Burgett’s obituary was the one that Joe Hagenbuch painted. I also believe it was not a coincidence that they met that day at the VA Hospital. Joe’s family needed closure. I’m so glad they finally got the answers they were needing for all those years about James “Jimmy” Hagenbuch. Thank you Mark and Andrew!