To Hell and Back: Prisoner of War, Shadrach L. Hagenbaugh

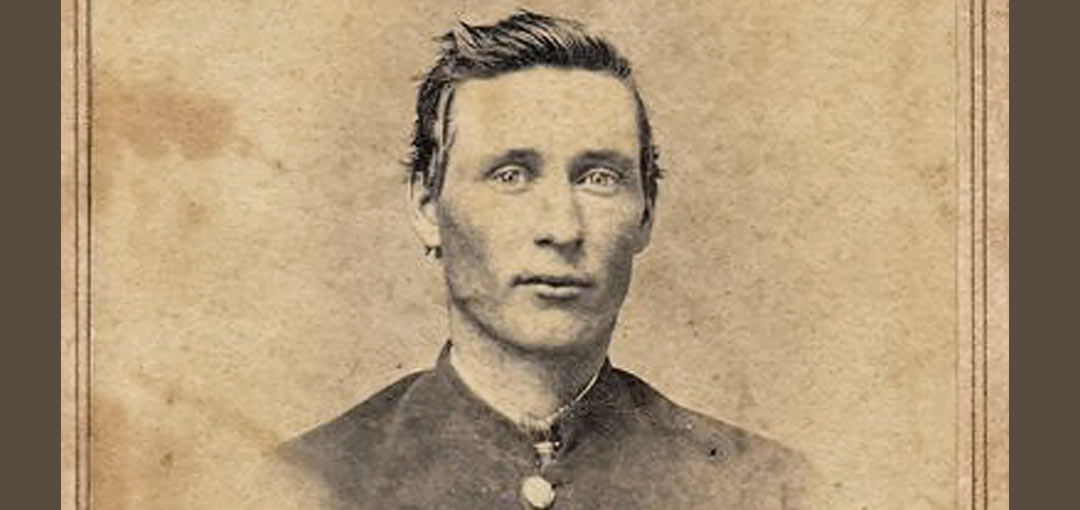

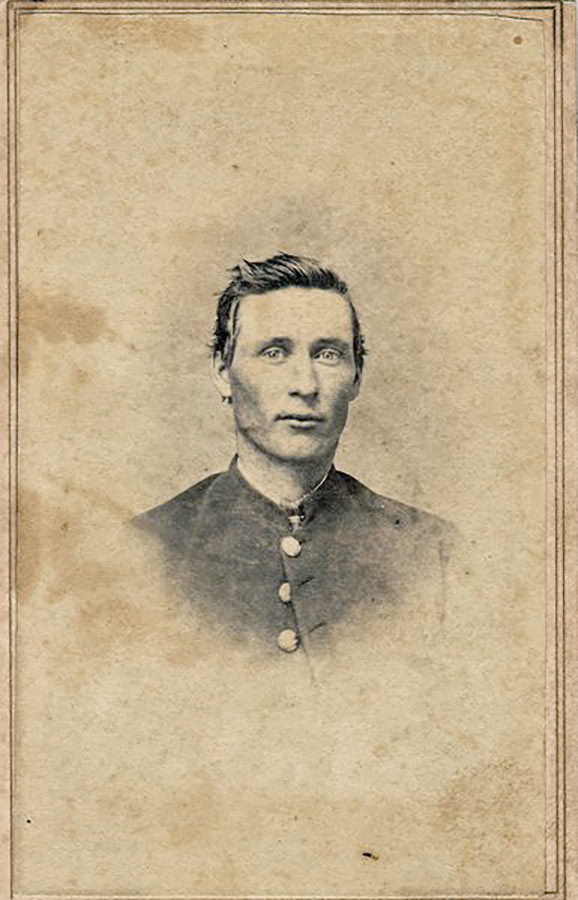

In 2018, I found a Civil War era photograph of Shadrach L. Hagenbaugh being sold online for nearly $200. According to the site that was selling it, Shadrach had served in the Union Army, was captured by the Confederates, and was released shortly before the end of the war. While I didn’t buy the image, I did take a screenshot of it for later review. Recently, I pulled up that screenshot and began to uncover the unsettling story of a Hagenbuch relative who experienced the horrors of war and lived to tell.

Shadrach L. Hagenbaugh was born on May 10, 1840 and grew up in Harveyville which is situated in Luzerne County, Pennsylvania. His father, Reuben (b. 1803) was born a Hagenbuch but later changed his name to Hagenbaugh. Shadrach’s line is as follows: Andreas (b. 1715) > Michael (b. 1746) > Christian (b. 1770) > Reuben (b. 1803) > Shadrach (b. 1840).

At the beginning of the Civil War, Shadrach volunteered for service and mustered into Company F of the 7th Pennsylvania Reserve Regiment (also known as the 36th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry) during July of 1861. He saw heavy fighting in a number of battles in 1862 including the Peninsula Campaign, South Mountain, Antietam, and Fredericksburg. In 1863, his regiment was stationed just outside of Washington, D.C. at Alexandria, Virginia. There it remained for the better part of a year. During this time, Private Shadrach Hagenbaugh sat for a photograph at the studio of Peter McAdams, creating the image that was sold online in 2018.

Late in the spring of 1864, the 7th Pennsylvania Reserve Regiment marched to join the Wilderness Campaign. On May 5th, the entire regiment, except for Company B, was cut off from the rest of the Union Army and surrendered to Confederate soldiers. A total of 272 men were captured, including Shadrach, and became prisoners of war. Their situation would only grow worse in the coming weeks.

An article from October 20, 1903 in the Wilkes-Barre Semi Weekly Record recounts the ordeal in a profile of Shadrach L. Hagenbuch:

[The regiment] was taken to Lynchburg, Virginia, then to Danville, Virginia, where the boys were put in tobacco warehouses for a week. They were then placed in box cars and taken to Andersonville Prison, Georgia. In the box car with Mr. Hagenbaugh there were seventy-one men. During the long imprisonment in this dreadful place, the men received only a pint of cornmeal every twenty-four hours, and the suffering was horrible. He, with a number of others, was made to sign a parole of good behavior and they were then taken to a place called Florence, South Carolina, where they remained a short time. They were then taken to Wilmington, North Carolina, and were exchanged on the North East River, ten miles from Wilmington.

Mr. Hagenbaugh was almost famished from hunger and weighed only seventy-five pounds with no shoes on his feet. In this condition, in February [of 1865], he walked to Wilmington, where he remained for several days. They were then put on transports and taken to Indianapolis. He secured new clothes at Indianapolis and then went to Harrisburg and from there to Philadelphia, where he was discharged, eight months having elapsed since his enlistment had expired. He was discharged April 1, 1865.

While the the above excerpt gives a sense of what Shadrach must have endured during his time at Andersonville Prison, it omits many of the events which led to him becoming a gaunt 75 pounds.

Patrick Hourigan of the 52nd Regiment was another Andersonville Prison survivor interviewed for the same article. He explained his experiences in graphic detail, shedding additional light upon what Shadrach would have lived through:

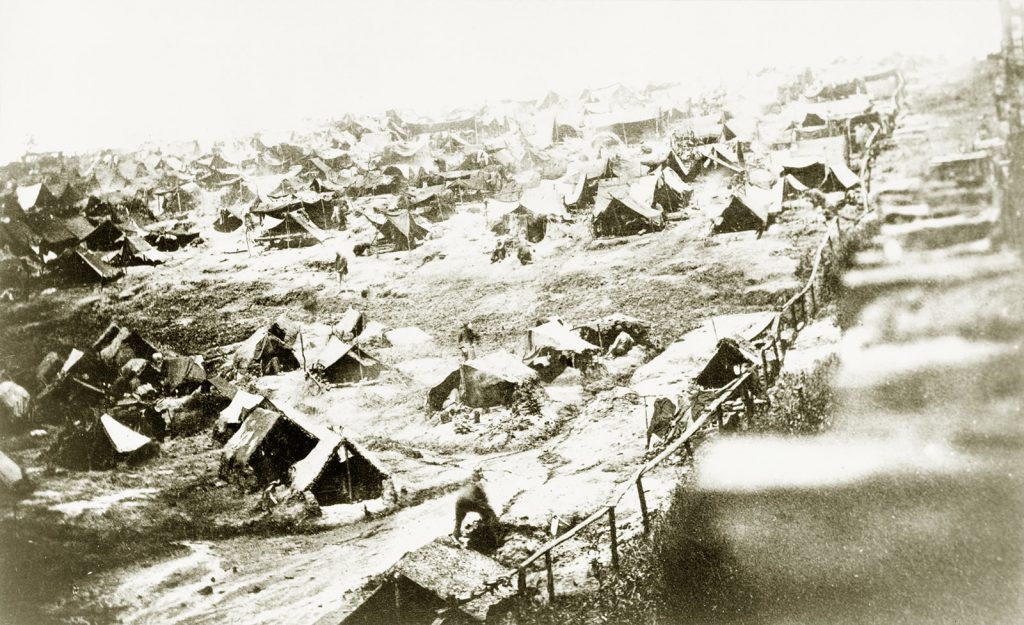

I was told shortly after we arrived that there were nearly 35,000 men shut up in that pen of twenty-six acres. We received no instructions or warning as to the rules and seeing a vacant strip of about fifteen feet around the inside of the stockade, some of us started for that place to make ourselves comfortable, but a soldier called out, “Look out for the dead line; they’ll shoot you if you go there.” So we had to be content with a few feet of ground in the midst of the multitude. I remember when we entered that the sight of the crowd and the hum of voices reminded me of a large swarm of bees, and that night I could not rest with the suffocating stench of the camp, the general unrest, the moans of the sick and dying, and the half hour calls of the rebel sentinels, telling that all was well with them.

We were closely examined and searched on our arrival and everything of value taken from us with the promise that it would be returned upon our release, but nothing was ever returned. Nothing was left us but the clothing we wore and I saw some almost naked, having sold their coats and shoes for food. After being there a month we became like the rest—wild looking, living skeletons, long tangled hair and scraggy beards, dirty, covered with vermin, and dying with hunger and disease.

The water we were forced to drink became something awful during the hot months of July and August—poison to drink it—but we had to or die of thirst. The stockade covered part of the two hillsides, with the stream of swampy water running through the center. This water was originally from a swamp and before reaching us ran through the rebel camp on the outside. It was black, filled with filth, and we had to brush a scum off the pools when we wanted some to drink. Those were awful days and the prisoners did almost everything but eat each other to keep alive. The pint of cornmeal we received each day for rations was generally eaten raw, as our party could get no wood to make a fire to cook it. Some negro prisoners sent out to work during the day would return with some small pieces of wood at night, which they would sell to those having a few cents, for the interior of the stockade was soon cleaned of firewood. I saw hunger in its desperate stages, saw when a prisoner would manage to buy a few sweet potatoes or a turnip and gorge himself with it, then sicken and vomit it up. Other prisoners would pick up the lumps from the vomit and eat it themselves.

Tents inside Andersonville Prison, August 1864. The dead line is the wooden railing running diagonal to the right side.

Hourigan continues:

It was awful the number who died during that summer. We were marshaled into detachments of 100 men each. I remember I was in the twenty-ninth detachment, and we had to line up our 100 men each day for rations, for if any were missing we would get none until the missing men were accounted for. If any of our squad died during the night, their bodies were dragged into line and counted with the living. Each man generally had a partner. . . . Some of the men dug holes in the hillside with their hands as shelter from the sun and rain and sometimes with a heavy storm the holes would fill with water and those who lay sick and unable to move would be drowned in them. The dead numbered hundreds day after day and were hauled from the stockade entrance in wagon loads.

The sufferings of some men were horrible. They would sell their shoes for food and then their feet would blister from the sun, sores would form, and the pest of flies would swarm over them, adding to their misery. Finally their feet would become so bad that the men could not walk and they would crawl around until their hands also became sore. Many would wallow in the stream of filthy water like hogs to escape the flies and the water would further poison the sores and death would result. Many became insane before they died.

Even the ground was covered with vermin and maggots. A prisoner would lie down on what he through was a piece of clean sand, and in the morning would find maggots on his clothing and in his hair and ears. Then to add to the desperation a gang of prisoners banded together as robbers, robbed and even murdered those whom they suspected of having money. We organized a police force and hanged six, which broke up the gang.

“War is hell,” said General William Tecumseh Sherman in a speech made after the conclusion of the Civil War. He was right.

Perhaps, after surviving the horrors of Andersonville Prison, Shadrach Hagenbaugh wanted to forget what had happened and move on with his life. This might explain his brief remarks in the article. With the war over, he found work as a carpenter in Wilkes-Barre, PA and married Elizabeth O. Hoyt. The couple’s only child, Ethel M. Hagenbaugh, was born in 1882. Eventually, Shadrach went into the picture framing business and opened his own store at 10 North Franklin Street in Wilkes-Barre.

Men of the 7th Pennsylvania Reserves photographed in 1906 for the Wilkes-Barre Centennial Festival. Shadrach L. Hagenbaugh is standing on the far right side of the back row.

On December 7, 1905, Shadrach Hagenbaugh returned to the former site of Andersonville Prison and attended the dedication of a memorial honoring the 1,849 Pennsylvanians who died there. This, along with a 1906 photograph of him sitting with comrades from his former regiment, demonstrate just how important his service during the Civil War was to him.

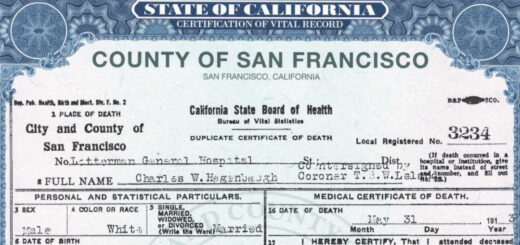

Shadrach L Hagenbaugh died on February 20, 1919. He is buried with his wife and daughter at Scott Cemetery in Luzerne County, PA.

While writing this article, I was reminded of how our Hagenbuch family can often be found participating in crucial moments of American history. As a teenager, I had learned about Andersonville Prison and even watched the acclaimed 1996 mini-series about it. Yet, I could never have imagined that one of own experienced firsthand the atrocities committed there and, even more amazingly, survived the ordeal to tell his story.

here is a lot that I could say about the subject of this article….but….I won’t. Thanks Andrew, as always….we are supposed to learn something new every day….thanks again.

Thank you, Uncle Dave, for your continued support! There are so many family stories left to be uncovered—many from the Civil War too. One element I didn’t include was that the day after Shadrach was discharged his older brother Caleb (b. 1828) was killed at the battle of Fort Gregg near Petersburg, VA. There was at least one other brother from this family that served in the Union Army too.

I am unable to trace my Hagebok ancester, but assume it to be a phonetic translation. My wife’s GreatGrandfather Bell also survived Andersonville with a twist. They mislabeled a body and when he was about 55 he went back for a visit to see his grave with marker not far from the prison site.

Hi Fred. Wow, is quite the story about finding his own grave there! Who is your “Hagebok” ancestor? This is almost certainly a Hagenbuch. Do you have their first name and another other dates or information? We might be able to make the connection. You can contact us directly through this form if you wish to share more detailed information: https://www.hagenbuch.org/contact-us/

My 5th GreatGrandmother, Effie Elizabeth Laub, 1701-1860, husband Johannes Martin Flick, 1778-1861, was, per a hand-drawn family tree descended from Laub 1755/Hagebok 1755. Being especially interested in my maternal lineage, I have repetitively searched for her parents. I have no doubt that they were among the flood of people from the Palantine that came in through the Philadelphia port. Mr Flick was a German that entered with his parents. Effie apparently lived her life in Lycoming Co. and is buried there, although her fine gravestone does not have her maiden name. Borne in Penn twp & buried in Hughesville. I am via the McCarty family and Silas was also a Civil War veteran. Thanks so much for your response and any thoughts about tracing my (Hagebok) connection highly appreciated, E. Fred Elledge, Oceanside, CA via Edwards Co, KS.

Hi Fred. I am going to send you an email today to the address you provided with your comment. I have some information which actually raises more questions and than answers.