Dying of Grief: Isaac W. Hagenbuch Sentenced to Prison

In 1884, family historian Enoch Hagenbuch (b. 1814) wrote:

The Hagenbuchs are not among the distinguished men and women of our beloved land. They are, nevertheless, almost among our best citizens. I never have been able to find the name on the prison or pauper catalogue, and it is to be hoped that none will ever so disgrace the name, coming to us untarnished from past generations.

Little did Enoch know that 15 years prior, one young Hagenbuch had left a black spot on the family name and may have even sent his parents to an early grave.

Our story begins with a brief article published in the newspaper, Crisis, on December 29, 1869. It reads as follows:

MICHAEL HAGENBUCH and wife, of Orangeville, Columbia County, both died last week of grief, occasioned by their son’s being arrested and imprisoned for theft.

Research shows that a Michael Hagenbuch of Orangeville, Columbia County, Pennsylvania died on November 30, 1869. His line is Andreas (b. 1715) > Michael (b. 1746) > Henry (b. 1772) > Isaac (b. 1801) > Michael (b. 1825). His wife, Keturah (Kitcher) Hagenbuch, followed him only four days later, with her passing on December 4, 1869.

Here appears to be the couple mentioned in the article. Yet, did this couple actually die of grief and, if so, why?

The US Federal Mortality Schedule from 1870 specifies the names of both Michael and Keturah Hagenbuch. However, neither is listed as dying from grief. Michael’s cause of death is noted as inguinal hernia—when part of the intestine bulges through the lower abdominal wall. Keturah’s is specified as enteritis—inflammation of the intestine often accompanied by diarrhea.

Many doctors debate whether it is even possible to die of grief. One theory is that the anxiety and stress caused by despair may be able to trigger a heart attack or stroke. Although, neither of these medical events is listed as the cause of death for either Michael or Keturah.

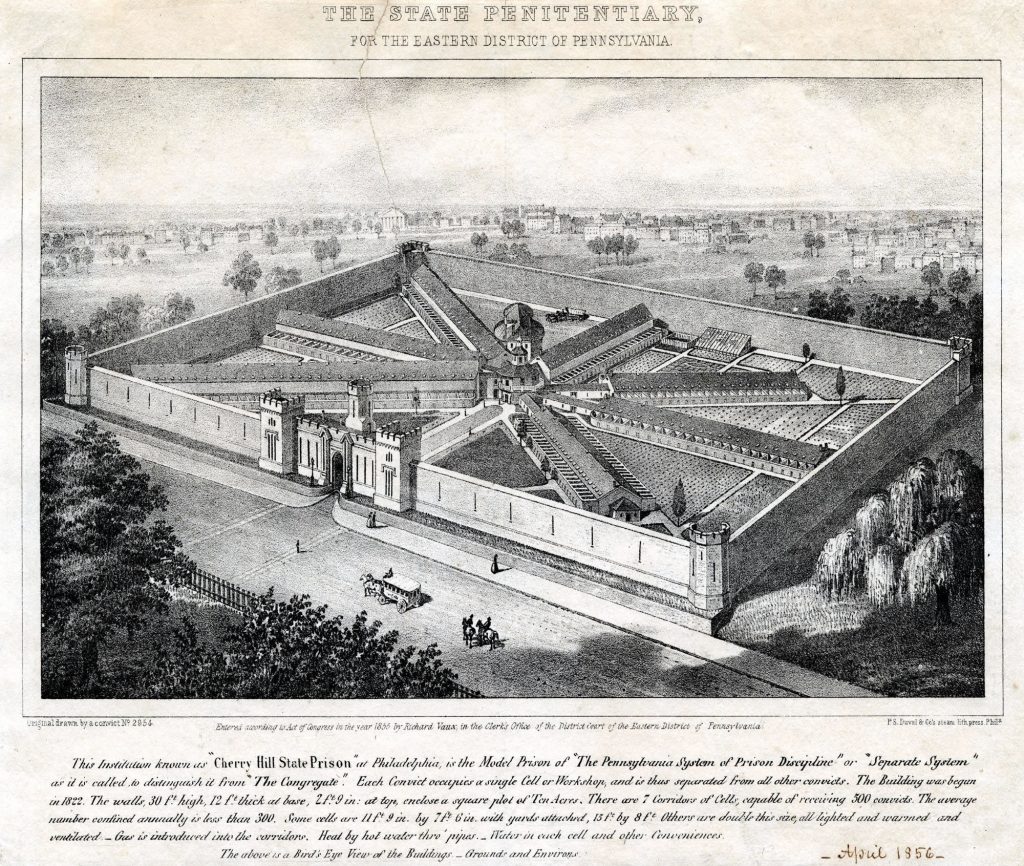

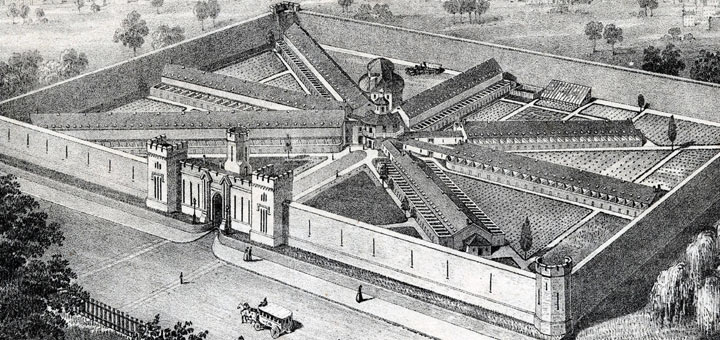

Yet, there appears to be good reason for the couple to have been anguished. The 1860 census reveals that they had two children: Isaac Wallace (b. 1852) and Torinda Salome (b. 1856). On December 9, 1869, five days after his mother died, 17-year-old Isaac Wallace was convicted of “larceny and receiving stolen goods.” He received a one-year and four-month-long prison sentence to be served at Eastern State Penitentiary in Philadelphia, PA.

The penitentiary’s convict register provides other notable facts about Isaac. He was five and a half feet tall with blue eyes, brown hair, and scars on his left wrist from a dog bite. He was able to read and write, was a moderate drinker, and had no living parents. Finally, he arrived at the prison wearing a ring and carrying some type of pocket book.

Isaac was incarcerated at Eastern State Penitentiary on December 10, 1869. The prison had opened in 1829 and was widely viewed as a revolutionary, new way to reform convicts and return them to society. Solitude, used to encourage personal reflection, was a key tenet of the facility. After visiting the prison in the 1830s, Frenchmen Gustave de Beaumont and Alexis de Tocqueville observed:

[T]he founders of the new penitentiary at Philadelphia, thought it necessary that each prisoner should be secluded in a separate cell during day as well as night… [The convict, once thrown into his cell, remains there without interruption, until the expiration of his punishment. He is separated from the whole world; and the penitentiaries, full of malefactors like himself, but every one of them entirely isolated, do not present to him even a society in the prison…

As solitude is in no other prison more complete than in Philadelphia, nowhere, also, is the necessity of labor more urgent. At the same time, it would be inaccurate to say, that in the Philadelphia penitentiary labor is imposed; we may say with more justice that the favor of labor is granted. When we visited this penitentiary, we successively conversed with all its inmates. There was not a single one among them who did not speak of labor with a kind of gratitude, and who did not express the idea that without the relief of constant occupation, life would be insufferable…

Isaac appears to have served out his sentence and returned to Columbia County. In 1873, he married Alice Minerva Mosteller, and the couple had a daughter, Emma Torinda (b. 1874). Perhaps to escape his past, after incarceration Isaac began to go by his middle name, Wallace. He died in 1931 in Meshoppen, Wyoming County, PA and is buried as Wallace Hagenbaugh.

All things considered, it is unlikely that Isaac’s conviction was the direct cause of his parents’ deaths. Instead, it appears a sad coincidence that the two fell ill and died just before his sentencing. From here, rumor and intrigue created a story that would grab the attention of newspaper readers.

Families, like the people who are part of them, are rarely perfect—regardless of what Enoch said. The untimely deaths of Michael and Keturah Hagenbuch, along with the conviction of their son Isaac, are a sad chapter in Hagenbuch history. That said, Isaac appears to have learned from his youthful mistakes and went on to live an otherwise normal life, something for which his parents would have certainly been thankful.