An Alarming History: Children and the Dangers of Fire

“Don’t play with fire!” What child hasn’t heard this phrase? Growing up, I know I did—especially when staying at the family cabin or on a Boy Scout camping trip.

Back then, I didn’t really think much of it. Sure, fire can be dangerous, but what was the worst that might happen? More often than not, the unsolicited advice of adults went unheeded, and I still lived to tell the tale. That said, not every child was so lucky.

I first realized this fact four years ago. On a late September day in 2019, I stood before a small gravestone at New Bethel Church, not far from the Hagenbuch Homestead in Albany Township, Berks County, Pennsylvania. The stone was for Matilda Hagenbuch, who had died a few months shy of her third birthday. I found myself moved by her death, perhaps more than usual, because I was about to become a father. I wanted to know more about her.

Matilda’s grave marker was beautifully engraved on a rough, lichen-covered piece of field stone. It reminded me of the memorials found at the Hagenbuch Homestead cemetery. It was inscribed with German phrases such as “Hier Ruhet Matilta” (Here Rests Matilda) and “Tochter Von Charls Hagenbuch” (Daughter Of Charles Hagenbuch). Whoever created it cared deeply for this child.

With the details from her stone, I consulted the Descendants of Andrew Hagenbuch that was published by Charles’ brother, Enoch Hagenbuch (b. 1814). In the history, Enoch writes:

[Matilda], daughter of of Charles, born [Dec] 16, 1846. Was severely burned and died from the effects Oct. 2, 1849.

Reading this gave me pause—more than that really—and I began to imagine the circumstances that led to a young child, not even three, being burned to death by a fire. Had she slipped and fallen into a large, outdoor bonfire? I tried to think about something else.

Matilda was the daughter of Charles and Julia (Fosselman) Hagenbuch. Her Hagenbuch line is: Andreas (b. 1715) > Michael (b. 1746) > Jacob (b. 1777) > Charles (b. 1819) > Matilda (b. 1846). Shortly after adding her information into Beechroots, my eldest son was born and the pandemic followed. I forgot about Matilda.

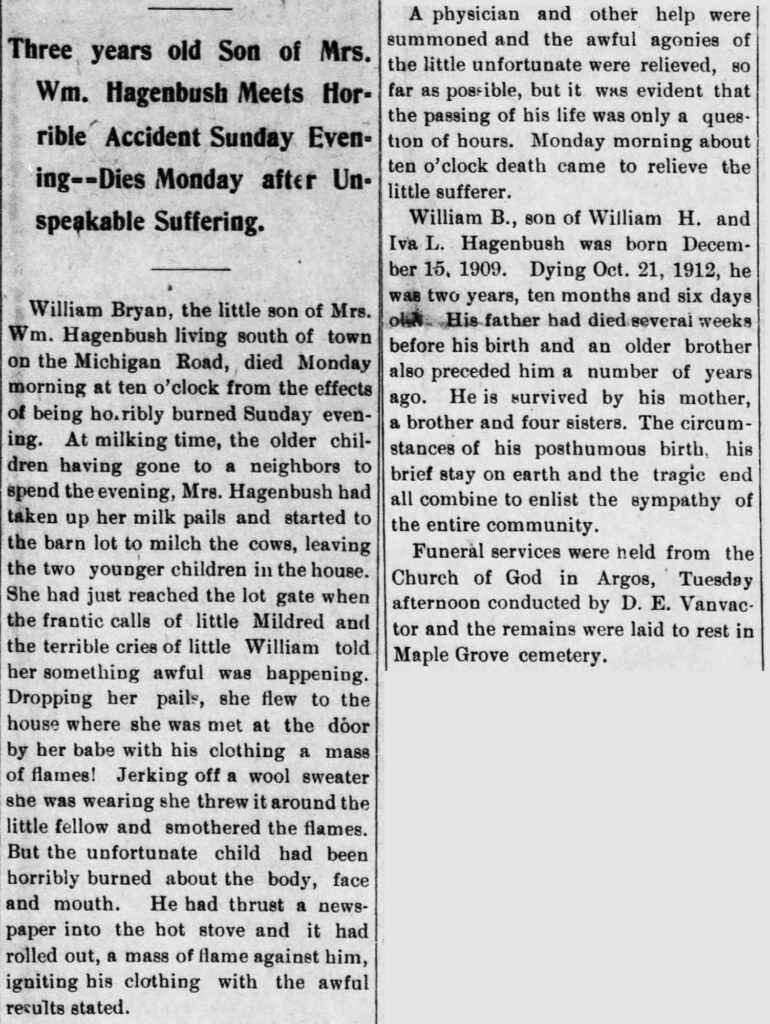

That was until a few weeks ago, when I was adding more family into Beechroots. I stumbled upon the story of William Bryan Hagenbush of Argos, Indiana. The following was published in The Argos Reflector on October 24, 1912:

William Bryan, the little of son of Mrs. Wm. Hagenbush living south of town on the Michigan Road, died Monday morning at ten o’clock from the effects of being horribly burned Sunday evening. . . . Mrs. Hagenbush had taken up her milk pails and started to the barn lot to milk the cows, leaving the two younger children in the house. She had just reached the lot gate when the frantic calls of little Mildred and the terrible cries of little William told her something awful was happening. Dropping her pail, she flew into the house where she was met at the door by her babe with his clothing a mass of flames!

Jerking off a wool sweater she was wearing she threw it around the little fellow and smothered the flames. But the unfortunate child had been horribly burned about the body, face, and mouth. He had thrust a newspaper into the hot stove and it had rolled out, a mass of flame against him, igniting his clothing with the awful results stated.

It was an appalling account, and I was immediately reminded of little Matilda. Both children had died just shy of their third birthdays. William was born on December 5, 1909 to William J. and Iva Leona (Bryan) Hagenbush. His line is: Andreas (b. 1715) > Henry I (b. 1737) > Henry II (b. 1786) > Jacob (b. 1820) > Israel (b. 1848) > William J. (b. 1874) > William B. (b. 1909). This group of relatives changed the Hagenbuch name to “Hagenbush” around the mid-1800s.

Article about the death of William B. Hagenbush from “The Argos Reflector”, October 24, 1912. Credit: Findagrave.com/Susan Pratt Habermann

I have written previously about child mortality. In this article, I noted that during the 19th century nearly 40% of the children in United States died before the age of five—a staggering number primarily caused by infectious diseases. Modern advances in sanitation and medicine have drastically reduced the mortality rate in children to less than 1%. Yet, there were other reasons that young children died, such as falls, drownings, and burns.

Unfortunately, there is a lack of detailed child mortality data for the United States before the 20th century. However, current reports show that deaths from fires and burns are more prevalent in the youngest children, those between the ages of zero and five. Knowing the behavior of my own sons, who are within this age range, these findings make perfect sense to me. There is a reason baby gates, cabinet locks, and outlet protectors exist! Young children can be a danger to themselves, particularly as their mobility increases and their curiosity grows.

And let’s not forgot that modern homes are significantly safer than those of the past. Few of today’s houses regularly burn wood or coal for heating and cooking. Light comes from electricity instead of candles or oil lamps. Simply put, children nowadays live in safer environments than their ancestors and still they die of accidental burns. One can only imagine how many more perished from fire in previous centuries.

Gravestone of William Bryan Hagenbush in Maple Grove Cemetery, Marshall County, IN. Credit: Findagrave.com/Kim White

While researching this piece, I found a blog series written by Dr. Vicky Holmes, an expert in 19th-century British History and death in the Victorian era. Her work proved to be quite enlightening, since it used primary sources to explore the fire-related deaths of children. According to her work, a fire was at the center of domestic life. Heating water, cooking, and warmth all came from a hearth or stove. Nonetheless, this area frequently lacked a fireguard (also called a fire screen) to shield people in the room from the fire. Homes that owned a fireguard often did not use it, since the item had to be moved to tend the fire.

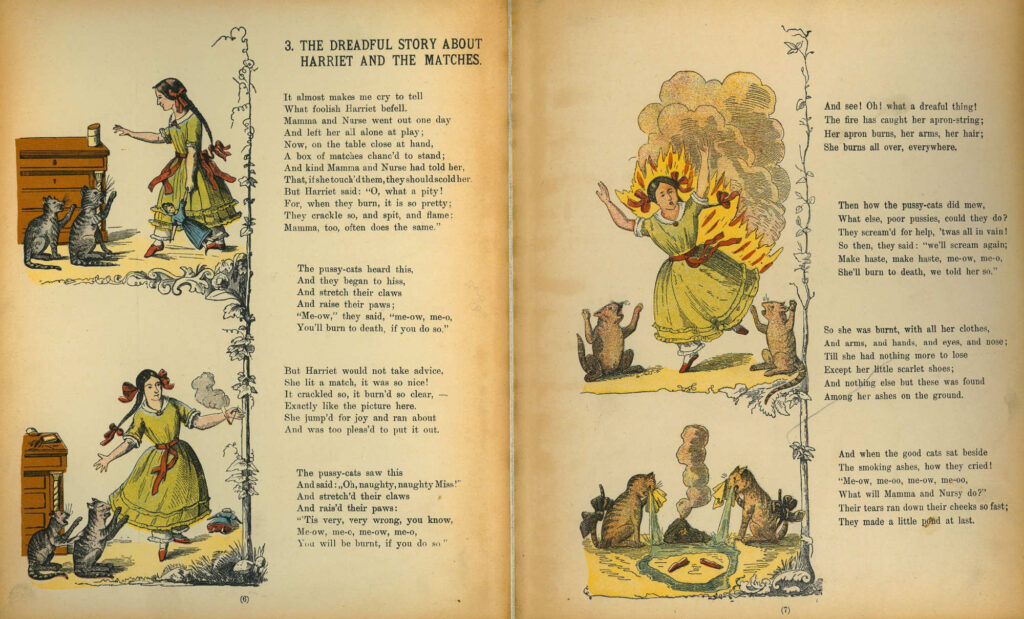

Without a barrier in place, children could quickly get into trouble, either by playing in the fire or by having sparks thrown onto their clothing. Holmes notes that flannelette, a popular textile used in Victorian children’s clothing, ignited easily and would adhere to skin while burning. She also highlights that the majority of young fire victims were between the ages of two and five and that they died during colder months when people spent more time indoors. Children were enticed by the flickering flame of a fire or lamp and would play in it. If their clothing caught fire and no adult was nearby to help, the situation could turn deadly.

Additionally, Holmes explains how many fire-related deaths were not from burns, but from scalds or poisoning. Children were apt to play near stoves, tables, and other places where pots of boiling liquids were placed. If these fell or were pulled over, a child could be scalded to death. Some children even died after sucking on matches, since these were once made with white phosphorous—a deadly poison.

“The Dreadful Story about Harriet and the Matches” from the book English Struwwelpeter by Heinrich Hoffman, 1848. Credit: Washington.edu

Before starting this article, I spoke with my father, Mark. He reminded me of a myth that women commonly died as a result of their long dresses catching fire. I actually ran across some discussion of this belief on a few blogs. The verdict: No, fire was not unusually deadly for adult women (or men). They were usually able to extinguish or remove a flaming piece of clothing before it became all consuming. However, the same cannot be said of young children, especially those lacking adult supervision.

Initially, I wasn’t sure I wanted to research such a disheartening topic. It is heart-wrenching to think of the horrible, senseless deaths of Matilda Hagenbuch and William Hagenbush. Yet, the circumstances that led to their deaths are an important piece of family history and something few of us think about today. Although they lived to be less than three years old and were born well over a century ago, these two children deserve to be remembered.