Birds of a Feather: 18th-Century Berks County

It is a known fact within my immediate family that my sister, Barbara (Hagenbuch) Huffman, is an avid birder. She began educating me 50 years ago when she would take Linda and me to Hawk Mountain here in Pennsylvania. Little did we know, as we trained our eyes skyward to identify migrating hawks and eagles, that below in the wide vista of farm land spread out in front of us lay the Hagenbuch homestead where Andreas Hagenbuch had settled in 1741. Of course, now when we take the hike up that mountain to watch those soaring birds, we can look out and pinpoint the homestead site.

Along with the sightings of those large birds, Barb also introduced me to song birds and so many other of our feathered friends. Inside the Visitors’ Center at Hawk Mountain was a large glass window with bird feeders outside which attracted all sorts of small birds. I learned to enjoy the sight of towhees, warblers, juncos, and the occasional titmouse. I learned to identify the buzz song of cedar waxwings, the bubbling chirp of wrens, the sad call of the mourning dove, and the hoot hoot of owls. For so many years, birds have been a part of my life. The thrill of watching pileated woodpeckers wack away at a tree, the dive of a kingfisher to catch a minnow, and the colorful flash of the bluejay gives me a warm feeling.

I never know when an idea will pop into my head and lead to me writing an article that is different than the names, dates, and places theme that most genealogists dwell on exclusively. In that vein, several weeks ago I wondered what birds our Berks County ancestors would have seen as familiar. I talked to my sister and her son, Tom, about this idea. (My nephew, Tom, has had the love of wildlife transferred to him.) These conversations got me ruminating on how to write this article. Then Andrew published last week’s article about Corkie Hagenbuch fishing for a pheasant. That story helps to introduce this article; Andreas Hagenbuch, in 18th-Century Berks County, never saw pheasants like we now have in Pennsylvania.

The Asian pheasant was introduced into Pennsylvania in the early 1890s for sport. At one time, they did propagate largely on their own. Growing up on a farm in Montour County, PA during the mid-1900s we saw many pheasants. As a boy, I did not know that the pheasants we chased through the fields with farm machinery were not originally part of Pennsylvania’s bird life.

This leads to the question: What birds would Andreas, his wives, and his children have seen in Berks County that are not common today? What birds do we see in the 21st century that our ancestors would not have seen in the 18th century? And, as some of you may be asking, what the heck does this have to do with genealogy? Well, for me, historic ornithology has a lot to do with putting ourselves in the place of our ancestors and understanding their daily lives.

Wild turkey. Watercolor by John James Audubon. Published 1827 in “Birds of America.” Credit: Audubon.org

First, let’s tackle this enjoyable subject with the obvious. Andreas and his family were certainly familiar with wild turkeys and grouse, which they would have hunted. Over the past 30 years, the turkey has made an amazing comeback in Pennsylvania. The Berks County Hagenbuchs would also have been familiar with the sight of owls, hawks, falcons, and eagles. All of these large birds have also made a comeback in Pennsylvania and, well, all over the United States. This is thanks in part to protective laws, the awareness we now have of preserving environments, and the outlawing of such poisons as DDT which caused eggshell thinning in predatory birds. I can imagine Andreas and his sons in the forests around the homestead hunting turkey and grouse and peering skyward as they hear the shrill whistle of a red tailed hawk, the shriek of an eagle, or as the sun sets, the hoot of an owl. Of course, the other large bird they would have been familiar with is the turkey vulture, that bird which often unnerves the uneducated who don’t realize the crucial part it plays in keeping our environment clean and healthy.

Yellow Warbler. Illustration by Benjamin Harry Warren. Published 1888 in “Report on the birds of Pennsylvania.”

There is no doubt that our early Hagenbuchs would have known the many songbirds that we admire today. The woods would have been filled with the flute music of the thrush, the tail flit of the insect eating phoebe, and the brilliance of the cardinal. Springtime at the family homestead in 1760 Berks County must have been a lovely time with budding trees, colorful wildflowers, and the animation of small birds. I can visualize mother Anna Maria Margaretha (Friedler) Hagenbuch, Andreas’ second wife, sitting with daughters, Elizabeth and Magdalena, while she has baby Christina at her breast. She points out a schön blau Vogel—a beautiful, bluebird—to the little girls or the Distelfink—the goldfinch. Many other birds are present too, adding color to the forest, bush, and fields of crops: flickers, tanagers, woodpeckers, grosbeaks, larks, red-winged blackbirds, and swallows.

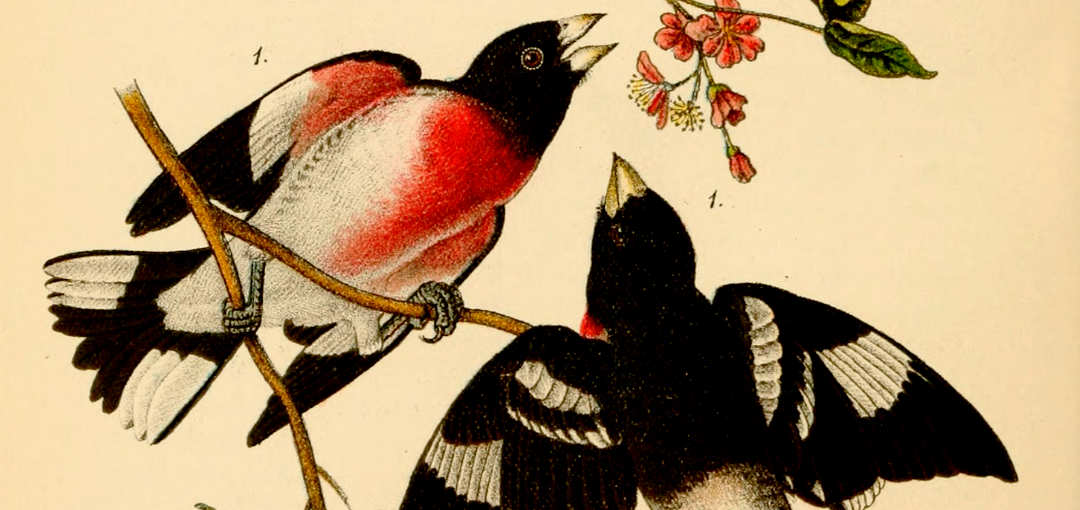

Rose-breasted Grosbeak. Illustration by Benjamin Harry Warren. Published 1888 in “Report on the birds of Pennsylvania.”

Along a branch of the Maiden Creek which still flows through the little valley where Andreas’ built his homestead were water birds. Ducks of several types would have been seen by our Hagenbuchs: wood ducks, the common mallard, and maybe even a bufflehead! A great blue heron wading through the creek, stalking and stabbing at frogs with its enormous beak, would have been a common sight at the homestead but no less fascinating. I imagine Andreas strolling along the creek watching the tall, blue wader which he addresses as a Reiher, when he catches sight of a black and orange bird fly up into a tree where it is building a hanging nest. “Ah”, he thinks, “similar to a German Pirol, which is called an oriole here in Pennsylvania.” He smiles because the colors are so vivid.

This Great Blue Heron showed up in our Hagenbuch backyard a few years ago. At 4 feet tall, our ancestors would have been as excited to see it along the Maiden Creek as we were when we noticed it feeding on voles!

But, one of the most wondrous sights which Andreas and his family would have seen and that we no longer enjoy is the flight of the passenger pigeons. We must thank the great artist John James Audubon for preserving the life of our country’s wildlife as it first appeared to him near Valley Forge, PA in the very early 1800s. His painting of the passenger pigeon reminds us of the delicate nature of our environment and the destruction that humans can cause to God’s creations. At one time the passenger pigeon population was estimated to be in the billions. But, by the early 1900s, because of mass hunting and loss of habitat, the passenger pigeon was near extinction. In 1914, the last passenger pigeon died in a Cincinnati zoo.

Passenger pigeons. Watercolor by John James Audubon. Published 1827 in “Birds of America.” Credit: Audubon.org

Along with looking skyward to watch the large predatory birds, Andreas and his family would have suddenly seen the sky darken as passenger pigeons in the thousands migrated as a massive swath. It would have been a sight to behold. Certainly, for some supplemental foods sources, our Berks County Hagenbuchs may have hunted the pigeons just as they did the turkey and grouse. However, unlike later “sportsmen,” our family would not have unloaded their fowling pieces just to kill and what few pigeons were taken would have added some variety to their diet of pork, chicken, mutton, and beef.

In conclusion, other than our 18th-century family not being familiar with the pheasant and we 21st-century Hagenbuchs not being familiar with the passenger pigeon, little has changed with the variety of birds 250 years ago. We birders still enjoy the colors, both brilliant and muted, of our feathered friends. We still stop and listen to a lovely bird song or a hawk’s whistle. We are still awed by the size of a turkey, the silent flight of an owl, a hummingbird’s speedy wing beats, and the delicate nature of a wren. As we ponder on the lives of Andreas and his brood, we must remember that they enjoyed all the beauty of God’s feathered creations. They were delighted and humbled by the natural world around them, just as we should be—every day!