Homestead Economics: Introduction

How did Andreas Hagenbuch (b. 1715, d. 1785), his immediate family, and his descendants make a living in the 18th and early 19th centuries? Today, we develop skills, find jobs, and build careers in specialized fields. A regular paycheck enables us to provide for ourselves and our families. Yet, on the frontier of colonial Pennsylvania, this system of employment did not exist and settlers like Andreas were required to be self-sufficient, creating their own economic systems for survival.

Over the years, we have explored numerous wills, inventories, and estate documents that were left behind by the owners of the Hagenbuch Homestead in Albany Township, Berks County, PA. Each provides a glimpse of a moment in time, recording what the family owned and suggesting how they supported themselves. However, to better understand what enabled the homestead to grow and thrive, it’s necessary to step back and analyze in greater detail the many industries conducted there.

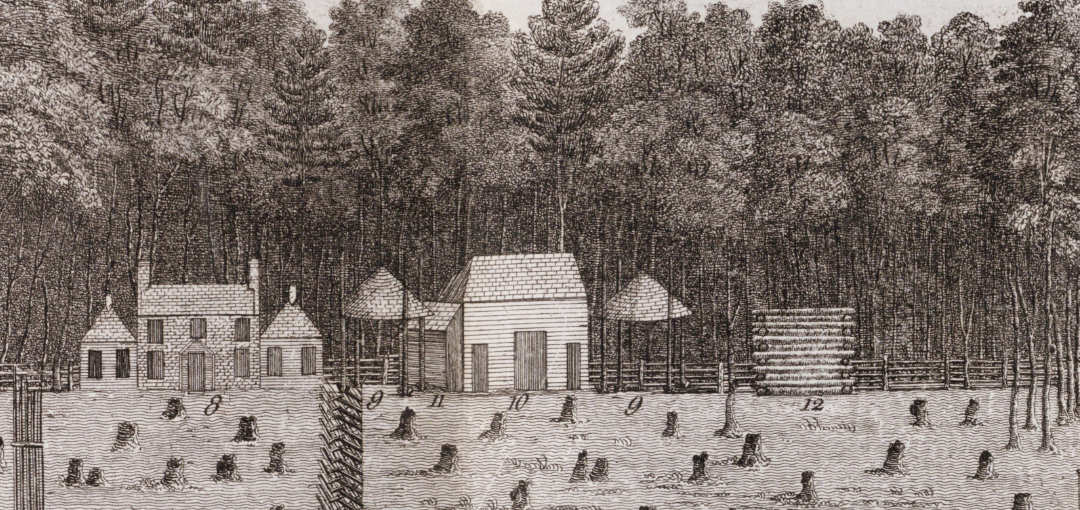

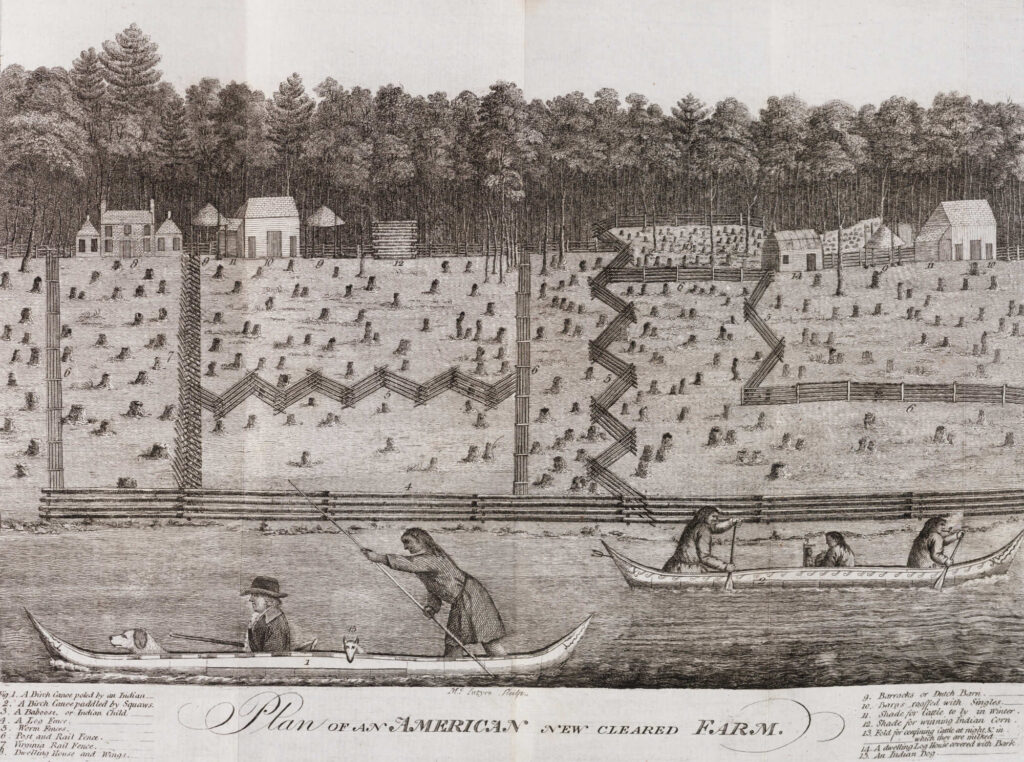

Andreas established his first homestead in Albany Township in the spring of 1738. He likely selected the site due to the availability of cheap land in an undeveloped, wilderness region known as the Allemangel. The location took several days to reach from larger towns and was 30 miles from Reading, PA and 40 miles from Easton, PA. As explained in a previous piece, the first parcel was abandoned after a few years in favor of another. The new property was warranted to Andreas in 1741, consisted of 150.5 acres of land, and became what we now know as the Hagenbuch Homestead.

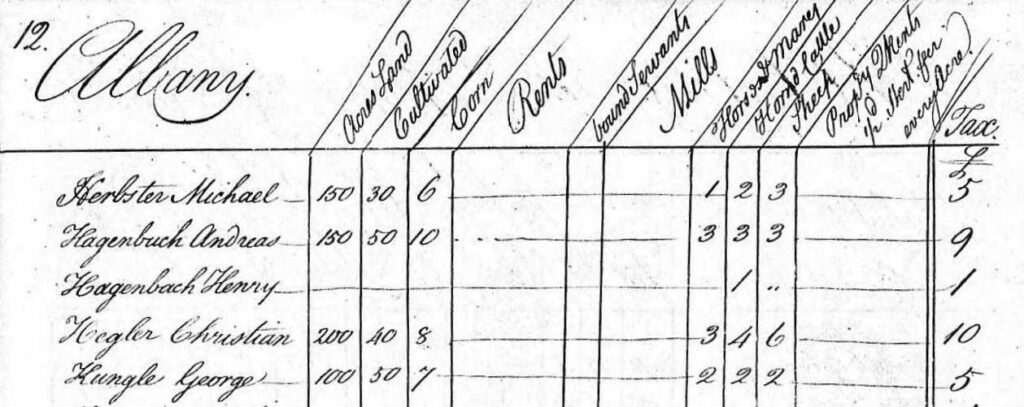

Tax list from 1768 for Albany Township, Berks County, PA showing Andreas Hagenbuch and his son, Henry.

The early years at the homestead were difficult. In 1741, the family consisted of Andreas, his wife Maria Magdalena (Schmutz), and their two young children, Henry (b. 1737) and Catharina (b. 1739). The family was the farm’s workforce. Andreas ran the farm, while Maria Magdalena cared for children. During this time, the Hagenbuchs were subsistence farmers—producing only enough food to feed themselves. Land had to be cleared of trees and rocks before it could be used for agriculture, meaning more work and labor. There was little room for error, such as a bad harvest or a serious injury. While it’s easy to imagine our ancestors living this hard life throughout the 1700s, subsistence farming was only the first economic phase of the homestead as it became more successful.

Research shows that colonial settlers typically cleared two to three acres of land per year. Tax lists for Albany Township, Berks County, PA support this premise and show that Andreas and his family cleared about two acres of land annually. In 1768, 27 years after Andreas had established the Hagenbuch Homestead, 50 acres of land were documented as cleared. By the next year, 1769, those 50 acres were noted as cultivated, confirming that the property was being used for agriculture. Some historians believe that colonial families needed around 50 acres of farmland to produce enough food to survive. The land could be cultivated with crops like corn or rye and used as pasture for grazing livestock animals including hogs and cows. Larger farms were able to grow more than they needed—cash crops—to be sold for profit.

By the late 1760s, the Hagenbuch Homestead had plenty of cleared land and a larger workforce. Along with several daughters, Andreas had two grown sons living at home: Michael (b. 1746) and Christian (b. 1747). Tax lists show that his eldest son, Henry, resided at the homestead or nearby too. With more workers and increasing prosperity, Andreas transitioned the property away from subsistence farming to more lucrative economic activities such as spinning yarn and distilling whiskey. Near the end of his life, in the 1780s, he even experimented with financing, offering interest bearing loans to friends and family.

Subsequent owners of the homestead tried other industries. Michael learned to tan animal hides and built a tannery there. When he purchased the Hagenbuch Homestead from his father, Andreas, the tannery and the distillery became two of its most important economic drivers. Michael’s son, Jacob (b. 1777), learned to weave. He took over the homestead in 1809 and continued the tannery, as well as expanded the amount of weaving done there. Jacob’s son, Michael (b. 1805), studied and taught German to local students. When he received the homestead, the tannery and the distillery were no longer in use. Instead, Michael focused on growing cash crops and raising livestock until his death in 1855, when the property was sold out of the Hagenbuch family.

To summarize, between 1741–1855 the economy of the Hagenbuch Homestead was focused on six main areas:

- Crops: rye, oats, potatoes, wheat, corn, and more

- Livestock: horses, cows, hogs, and sheep

- Textiles: linen and wool yarn and fabric

- Tannery: leather making

- Distillery: whiskey production

- Financing: interest-bearing loans

The above list illustrates the diversity of activities conducted at the homestead and contrasts with the idea that our earliest ancestors were simple farmers. In preindustrial America, Andreas, his immediate family, and his descendants were engaged in a number of cottage industries. Eventually, their ambitions would outgrow the original homestead property and require the acquisition of other parcels in and outside of Albany Township. In at least one notable case, Andreas bought land to the east near the growing city of Allentown, PA with the goal of building a distillery and supplying whiskey to this new market.

Through future articles in this series, we will dig deeper into the homestead’s primary economic activities. We will examine the efforts that went into these and how they contributed to the success of the farm. Finally, we will work to tell the story of the rising fortunes of our relatives who lived there—along with their eventual decline—in order to paint a more detailed picture of life at the Hagenbuch Homestead.

Congratulation on your exhaustively researched article on flax and linens! My grandfather (Ray S Winey of Richfield, PA) was given a linen bed sheet that was supposedly of fiber spun by his mother! I could never piece together the process from the plant to the sheet.

Like your ancestor, his father was a tanner of Juniata County and not involved in agriculture, so I assume that his wife either purchased the flax and spun it or traded for it. It is so evenly fine that she must have been experienced…but there are no other such fabrics in the family. Would I assume that she sent her threads off to be woven as I doubt that a travelling weaver would produce such even quality. My grandmother cut the sheet up and made place mats that I have tucked away…and labelled.

Have you any surviving fabrics of the family?

Keep up the excellent work…I am sure I am not the only non-Hagenbuch that appreciates your work and devotion! As we now say…. your “content” is aways a delight to see on my Gmail screen!

Thank you, I’m very impressed at all this information. It is such a pleasure to make our Heritage so real.

The farming in our branch went all the way down to my grandfather. Andrew Pierce Hagenbuch 1881-1963.

Norma Kay Hurter