HB: the Hagenbuch Family Ligature

Hagenbuch is a long last name. Normally, this doesn’t pose too much of a problem. However, when engraving on a stone or other constrained space, the Hagenbuch name can be a tight squeeze. As a result, some Hagenbuchs have abbreviated their name using a stylized, HB ligature.

A typographic ligature combines two or more characters into a single symbol. For example, a common example of a ligature is &, which is known as the ampersand. Believe it or not, the ampersand is actually a stylized combination of the letters e and t. Together these from the word et, which is the Latin word for “and”.

Ligatures originally developed as a stylized shorthand for combining nearby letters. This saved space and enabled Medieval scribes to write faster while copying books. Even with the invention of typesetting and the printing press, some ligatures lived on and were carried over from handwriting.

It wasn’t until the 20th century, that the use of ligatures began to significantly decline. This can be attributed to the adoption of less ornate, sans serif fonts, as well as the widespread use of typewriters and later computers. The ligature, which had made handwriting faster, simply wasn’t needed anymore in an era of mechanization, keyboards, and computers.

Currently, there are three known examples of the Hagenbuch family name being abbreviated as HB and using a stylized ligature. All of these date from the 18th and 19th centuries and are found at the Hagenbuch homestead in Albany Township, Berks County, Pennsylvania.

In all three cases, the H and the B are combined together along the right edge of the H and the left side of the B. The above example shows the HB ligature on the gravestone of Anna Magdalene “Brobst” Hagenbuch who died in 1781. She was the first wife of Andreas Hagenbuch’s son, Henry. The AM clearly represents her first and middle names, the HB her last name, and the IN is the German suffix showing that she was female.

In the next example seen below, the HB ligature is visible on the gravestone of Jacob Hagenbuch, grandson of Andreas Hagenbuch. Though he died over 60 years after Anna Magdalene, his stone clearly uses the abbreviated version of Hagenbuch on his stone. Without a doubt, this was done to save space and to continue the visual motif found on other stones in the homestead’s private cemetery.

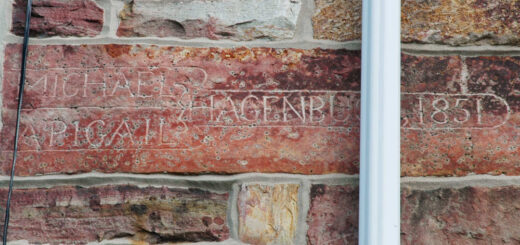

The last example is found etched onto one of the stone walls of the Hagenbuch homestead’s summer kitchen. This stone notes the year the structure was completed, 1852, as well as the owner of the property at the time, M. HB. These initials are those of Michael Hagenbuch, the great grandson of Andreas who died only a few years later. It is unknown who the H. H. is at the top of the stone. It could be the stone mason or Michael’s son, Harrison Hagenbuch.

The HB ligature was used by at least three generations of Hagenbuchs who lived on the homestead. In addition, it is likely that it was used by a fourth: Andreas Hagenbuch. One theory is that the HB may have been first used by the Hagenbuchs in Europe and was brought by Andreas when he settled in Pennsylvania.

Whatever the case, its use appears to have ended around the mid-1800s. Michael Hagenbuch died in 1856 and was buried at New Bethel Church. His gravestone, still visible today, is engraved with his full last name. The HB ligature seemingly died with him.

Today we are lucky enough to have rediscovered a piece of Hagenbuch history. Not only does the ligature reveal creativity and culture within the family, it also provides insights into the evolution of handwriting during the last few hundred years.

You might consider using the HB ligature the next time you sign your name and are short on space. If you do, you’ll be helping to keep this unique family tradition alive.

Thank you for the interesting history lesson.

Thank you for this very interesting article! I was just wondering about the gravestone for Anna Magdalene Brobst Hagenbuch. My husband is a descendant of Anna Magdalene and Henry Hagenbuch through their son John who married Elizabeth Knauss.

I have never found birth or death dates for her. I would like to know how you can be sure that this is her gravestone. I was also curious why she would be buried in Albany Twp. when Henry was living in Allentown in 1781. Thank you for your help!

Hi Elizabeth. Nice to hear from you! At this point, it is just guesswork based upon dates and names. You are right. Henry was probably in Allentown in 1781, but there also appears to be some evidence he may not have been. I will email you to discuss directly!