Finding Twin Sisters Through Collaborative Genealogy

Genealogy is a collaborative process, as demonstrated by my father, Mark, and I working together on this site. Teamwork enables us to bounce ideas off of each other and check our findings. It lets us explore different family lines and document our Hagenbuch ancestors more quickly. Cooperation even extends beyond my father and me to include other genealogists, researchers, and people who are interested in the work that we do.

One of these is Karen Deleon. She was recently mentioned in the article, Bringing Together Family: The Children of Conrad Hagenbuch. While investigating her own family, Karen discovered that she was related to us through her ancestor Sarah (Hagenbuch) Hower—a previously undocumented daughter of Conrad and Mary (Ruckle) Hagenbuch. Karen’s research sources included family history books, cemetery records, and census records. Some of these provided birth and death dates for Sarah that fit with what we already had documented for this family group, while others did not.

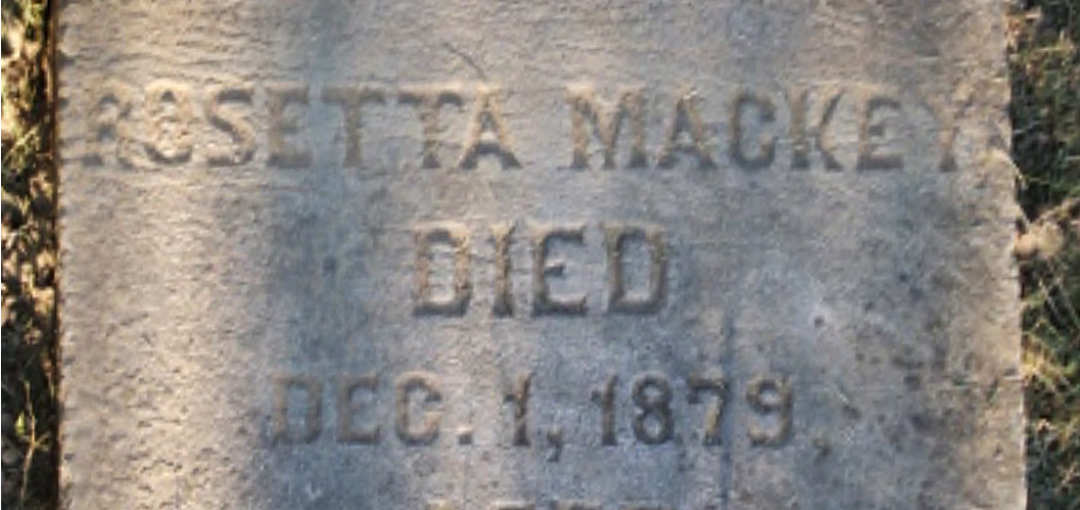

For example, we knew that Sarah had a sister, Rosetta (Hagenbuch) Mackey. According to Rosetta’s gravestone, she died on December 1, 1879 at the age of 55 years, 8 months, and 24 days. This placed her birthdate on either March 7, 1824 or March 8, 1824, depending upon whether days or months and years were subtracted first. (Occasionally, this order of operations makes a difference.)

One of Karen’s initial sources for Sarah (Hagenbuch) Hower’s dates was the book The Descendants of Hans Miehll Haur 1720–1970 by Jane (Hower) Auker. In it, Auker states that Sarah was born on September 8, 1821 and died on April 11, 1853. This birthdate fit perfectly between Sarah’s siblings Esther “Hetty” (Hagenbuch) Moyer (b. 1817) and Rosetta (Hagenbuch) Mackey (b. 1824).

Sanctuary and altar inside Messiah Lutheran Church in Mifflintown, PA. Credit: Facebook.com/Messiah.Lutheran.Mifflintown.PA

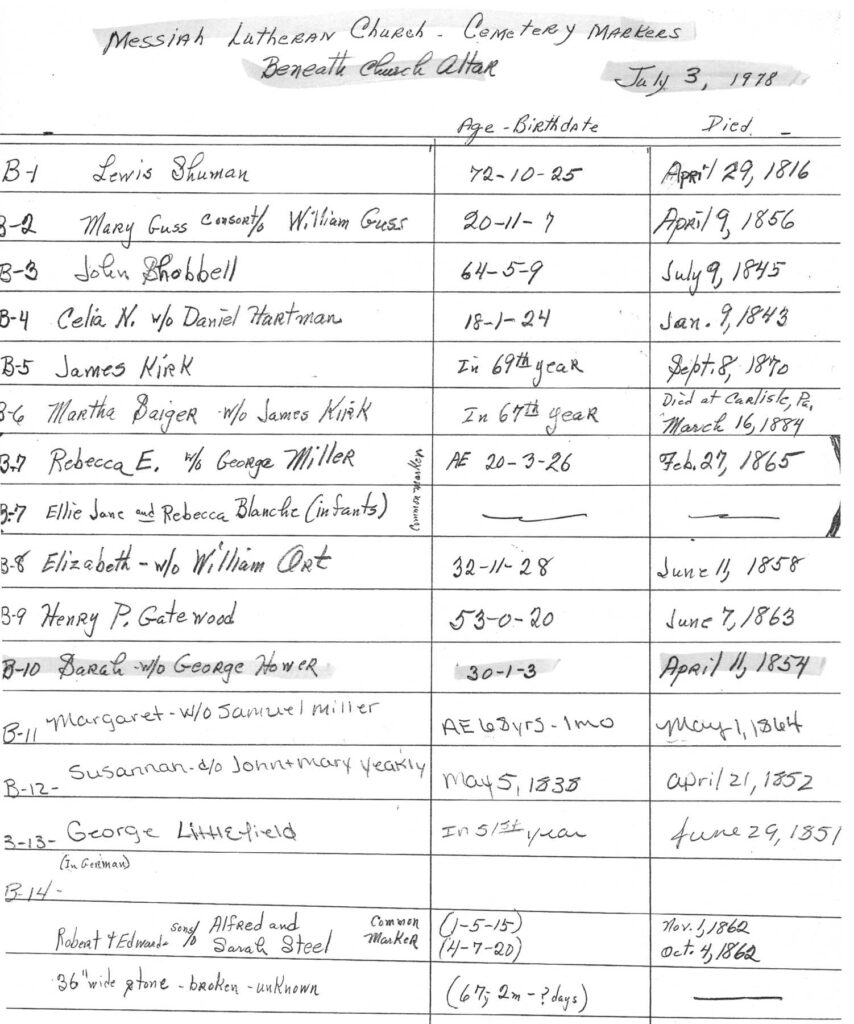

Karen wasn’t convinced these dates for Sarah were correct and, like all good genealogists should, she went in search of a better source. Family histories, after all, are often riddled with errors, as we have discussed before when exploring the dates for Henry Hagenbuch! I suggested that she reach out to the Juniata County Historical Society, since we believed Sarah was buried at a church in that area. Sure enough, Karen’s due diligence paid off, and she received a copy of the cemetery records for Messiah Lutheran Church in Mifflintown, Pennsylvania with an entry for Sarah (Hagenbuch) Hower.

According to the document dated July 3, 1978, Sarah’s gravestone was removed from the cemetery and stored in a space under the altar of the church, along with other old stones. Hers was inscribed with the date she died, April 11, 1854, and her age at time of death: 30 years, 1 month, and 3 days. Karen used this information to come up with a birthdate of February 8, 1824 for Sarah. When she emailed me with her findings, I replied with the following:

1824 cannot be Sarah’s birthdate unless she was a twin. Her sister, Rosetta, was born in March of 1824. Their father, Conrad, wrote a will that lists [Sarah] between sisters Esther (b. 1817) and Rosetta (b. 1824). As a result, I am apt to go with Auker’s dates here.

I must admit that I didn’t check Karen’s calculation for Sarah’s birthdate. Therefore, when I wrote my article about Conrad Hagenbuch’s family, I stuck with Auker’s dates for her. Karen saw the piece and sent me another email. She had since revised Sarah’s birthdate to March 8, 1824—the same as Rosetta’s. Using the details from the cemetery records, I checked the calculation and confirmed it was correct.

Record of gravestones stored beneath the Messiah Lutheran Church altar. Sarah is entry B-10. She was married to George Hower. Credit: Juniata County Historical Society

“Do you think they could have been twins?” Karen wondered in her message. Now, I was wondering the same thing!

Genealogy frequently requires separating the signal from the noise. This forces one to discard derivative sources like family histories and focus on original documents. Unfortunately, no baptism record for Sarah (Hagenbuch) Hower has been found, and her gravestone is no longer on public view. Even so, we do have the cemetery records from the Messiah Lutheran Church, which were carefully made when the stones were placed in storage. While going through the records, it became clear that the people who transcribed the stones documented what they could read and didn’t make guesses. Illegible characters were replaced with a “?” to show they were worn beyond recognition. No questions marks are found in Sarah’s entry, suggesting it was easily read.

Three censuses were done before Sarah died in 1854. Prior to 1850, only the head of the household was listed by name. The rest of the family members were simply tallied by age group. The 1830 census shows two females in the 5–10 years old column for Conrad Hagenbuch’s household, and the 1840 census has two females in the 15–20. This supports that he had two daughters born between 1820 and 1825.

The 1850 census is even more interesting. By then, Sarah was married, as was Rosetta. Both are recorded as 27 years old, suggesting they were born within a year or less of one another. Yet, if they were born in 1824, they would have been 26 years old not 27. Errors with ages are extremely common in early censuses. In some ways, this makes it even more surprising that the two sisters, now living with their husbands, are recorded as the same age.

“What are the chances?” I kept wondering. Was it a mere coincidence that the census showed they were born in the same year? Was it pure happenstance that their gravestones indicated they were born on the same day of that year too? Karen’s hunch, the one I had initially dismissed, appeared to be correct. Sarah and Rosetta were more than sisters—they were twins!

This revelation suggested something about Rosetta’s name too. Conrad and Mary (Ruckle) Hagenbuch had selected rather traditional names for their daughters Elizabeth, Mary, Esther, Sarah, and Rebecca. Only one really stood out—Rosetta. Though the name (meaning “little rose”) had been used for centuries, it came into vogue after the Rosetta Stone was discovered in 1799 and gained international attention. Hailed as a “remarkable” discovery in newspapers around the world, parents began naming their daughters “Rosetta” in increasing numbers.

It’s easy to imagine Conrad and Mary, surprised by the birth of a twin daughter, giving her a name befitting of the remarkable event. Before the 20th century, twins were a rare occurrence, comprising only about 1% of births. (Today, the rate is over 3%.) It was even more unusual for the twins to survive to adulthood. For instance, we know that Christian and Susanna (Dreisbach) Hagenbuch welcomed fraternal twins in 1792, though they died as infants.

While it is impossible to say with complete certainty that Sarah and Rosetta were twins, our best sources point to them being the same age and show they were born on or about March 8, 1824. Much of the credit for this discovery goes to Karen Deleon, and her persistence as a genealogist. Through her willingness to share information and collaborate, we are not only able to have a clearer picture of Conrad Hagenbuch’s children, but we are also able to connect Karen’s line to our Hagenbuch family tree.

Welcome, Karen, and thank you for your hard work and research!