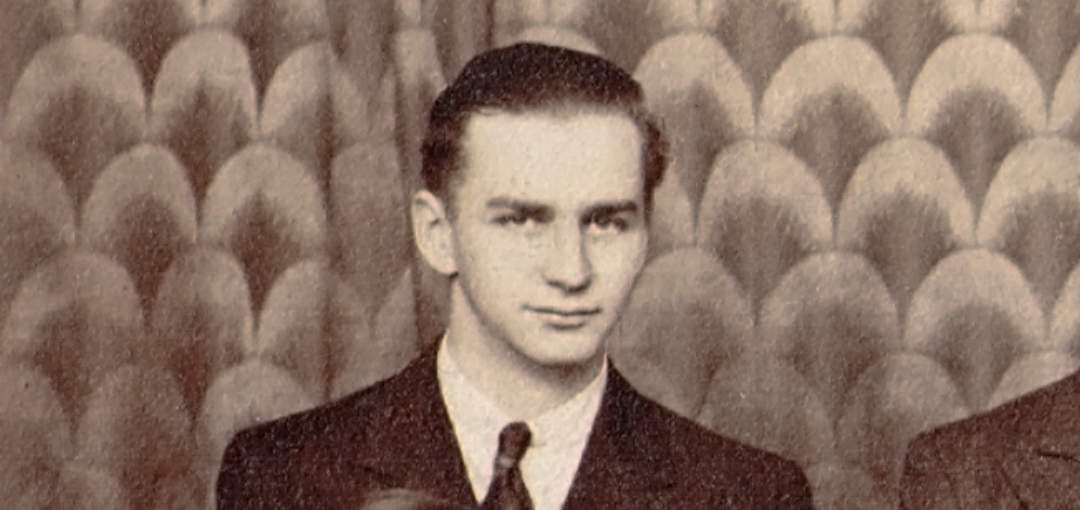

My Uncle Charles: I Hardly Knew You

Many of you, like me, probably have an uncle, aunt, cousin, grandfather, or grandmother whom we wish we would have taken the time to sit with and visit. I don’t mean to quiz them about their life’s statistics, but just to visit and get to know them better. For me, that person is my Uncle Charles.

Charles Clarence Hagenbuch is the oldest brother of my father, Homer. Uncle Charles was born in 1915 in Montour County, Pennsylvania and died in 2001 in Worcester, Massachusetts. While the rest of my aunts and uncles lived near me while growing up, Uncle Charles, his wife Aunt Leona, and their two children, my cousins Gary and Gayle, lived in the Worcester area. I remember visiting with them once when I was a young boy, and Uncle Charles did come back to Limestoneville when his father, my “Pap Pap” Clarence, died in 1967.

My father always told me that his brother Charles was the history buff in the family. When Dad, Andrew, and I attended his funeral in Worcester in 2001, my cousin Gary took me into Uncle Charles’ bedroom and there arranged on the bookshelves were many, many books about the history of the United States and other countries. If I remember, these weren’t historical fiction. Rather they were, as I call them, pure history, well-researched books. This was a man I could have related to in so many ways.

For several reasons, we never seemed to be close to Uncle Charles or his family. Charles had left the farm in Montour County early on to make his own way. He landed in Massachusetts where he raised his family and my parents kept in touch with him off and on. I remember, as a boy of about eight, going to visit Uncle Charles and Aunt Leona at their home in Worcester. We stayed a few hours to visit and then traveled on to some other destination. Towards the end of Charles’ life, in 2001, my father was in contact with his brother more often. I know that they telephoned back and forth on a regular basis. When Uncle Charles died, it was important for Dad to attend the funeral. Not only was this an excursion so Dad could pay his last respects to his oldest brother, but since I drove, Dad rode, and Andrew accompanied us, it was also a bonding experience for three generations of Hagenbuchs.

When I reviewed the idea behind this article with my first cousins, Leon Hagenbuch, Joe Robb, and Kathleen (Robb) Shuler, they remembered similar experiences. Uncle Charles and Aunt Leona visited with Leon’s father and mother (my Uncle Lee and Aunt Lera). Lee, Sr. was my father’s youngest brother. Joe and Kathleen’s mother, my Aunt Florence, also kept in touch with Uncle Charles towards the end of his life. Florence was my father’s oldest sister.

Clarence and Hannah Hagenbuch’s family, 1939. Top: Charles, Homer, Wilmer, and Lee. Bottom: Mary, Florence, Clarence, Hannah, and Ellen

A few months ago, Leon called me and said he had found a box of old letters and papers belonging to Uncle Charles in his farmhouse attic. He does not know how it got there, but it is another “box of goodies” similar to what I wrote about last year. Leon told me he wanted to give me this box which contained some very interesting information about our Uncle Charles. He went on to completely pique my interest about its contents with: “Did you know that Uncle Charles took some radio repair courses in Chicago?”

The box is filled with a lot of paraphernalia, some of which I will write about in a future article. But, the most interesting pieces have to do with Uncle Charles’ interest in leaving the farm community he had grown up in. These pieces, mostly letters, were at first difficult to understand until I arranged them chronologically. What appeared was the story of a young man who was doing his best to further his education and become “upwardly mobile,” so he could leave the life of his Hagenbuch family and become a professional in a line of work that did not include agriculture.

In July of 1934 at the age of 18, Uncle Charles wrote a letter to Dean Watts of Penn State College (now Penn State University) asking if he could get a job at the college and register for courses. He received an application to apply for work and instructions on how to apply for classes starting in September of 1934. The application was never completed.

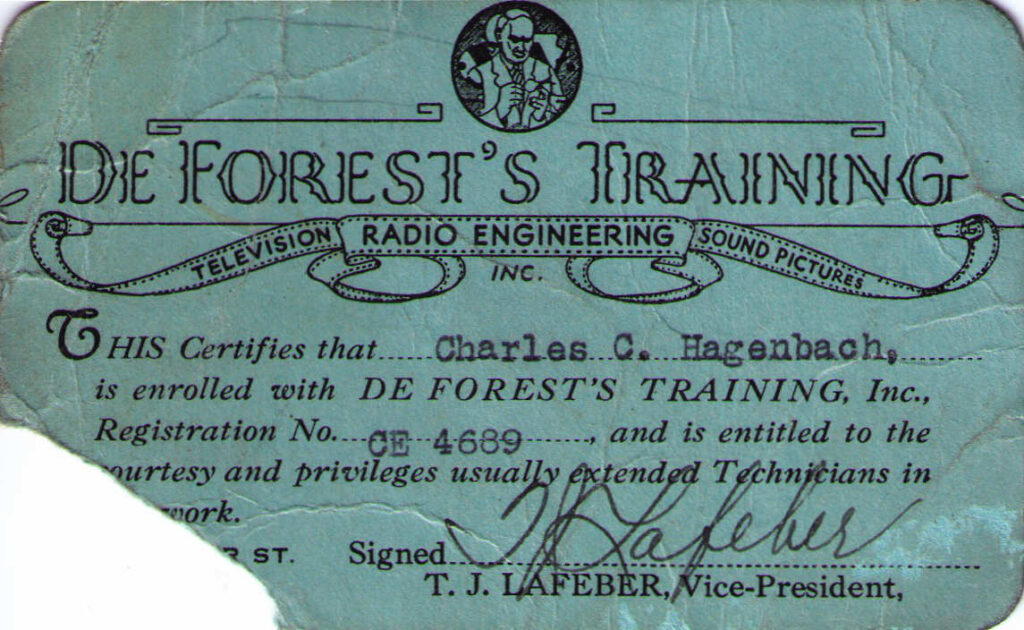

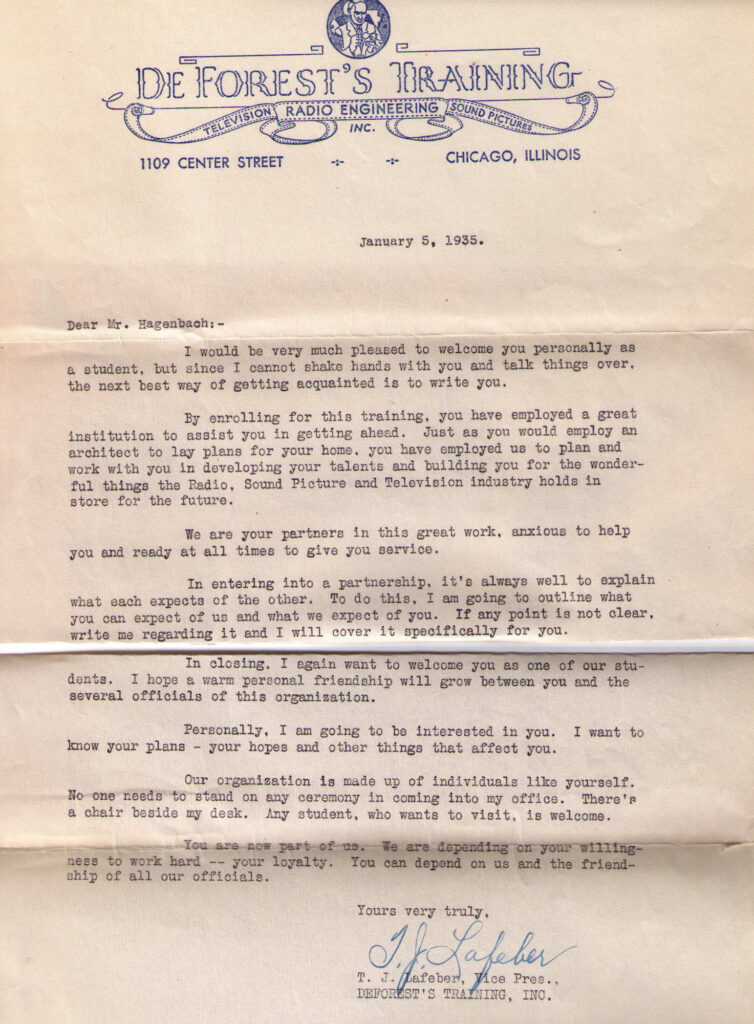

Then somehow Uncle Charles found out about DeForest’s Training, Inc. DeForest’s was founded in 1931 in Chicago by Herman DeVry and trained people to repair radios, film projectors, and televisions. After DeVry’s death in 1941 it was renamed DeVry Institute and is still in existence today. In January of 1935, Uncle Charles was accepted into the training program at DeForest’s. Preserved among the many letters in the box is the acceptance letter from the school’s vice president, T. J. Lafeber with a syllabus outlining the expectations and course requirements. There is also a blue enrollment card.

In addition to the letter sent to Uncle Charles, a letter was sent to his father Clarence which also outlined for parents what the correspondence courses were all about and advising parents to support their young man by “giving him a pat on the back”! Three weeks later a letter was sent to Clarence, Uncle Charles’ father and my grandfather, from the auditor of DeForest’s Training reminding “Pap Pap” to make prompt payments.

The payments were to be made monthly for tuition and eventually the purchase of a film projector that was to be sent to the home near Limestoneville, PA. It’s difficult to nail down exactly how much was being paid monthly and if there was an initial payment. But, in March the school’s Secretary of Student Services wrote to father Clarence apologizing that there was a misunderstanding and that Uncle Charles needed to complete 60 lessons, tuition cost of $139.50, before he could actually attend the “laboratory” in Chicago to complete his education. Additionally, he needed to find his own place to stay and pay for his own room and board. This was a lot to ask of a farm boy from Montour County, Pennsylvania—not only the money but also going to the big city, all alone, and living on his own.

The saga continues and Uncle Charles, while working on the farm with his father, mother, brothers and sisters, was burning the midnight oil to complete 60 lessons through the mail. On March 14, 1935 father Clarence received a letter thanking him for payment of $18 with a balance of $105.50. He writes that “Charles got a 97% on lessons 18 and 19. He is doing mighty fine work.” A month later Uncle Charles was sent a letter from W. H. Littlewood, DeForest’s Director of Education, stating he might want to complete 80 lessons which would include “sound training” and Charles could get a room at the YMCA on Larrabee Street in Chicago for as little as $3 a week. And, Uncle Charles was sent another enrollment agreement because Littlewood didn’t think Charles had a clear understanding of what he had agreed to! Of course, this all sounds a bit fishy to me.

Nevertheless, at the end of 1935, Uncle Charles must have completed enough work (or father Clarence had paid enough money!) that W. H. Littlewood wrote to Charles stating that beginning on March 2, 1936 courses for Electronic Engineer would be held at the DeForest’s Training lab in Chicago. Littlewood wrote: “The work you have done so far demonstrates your ability for persistency.” This would be a two week course, and the room and board at the local YMCA would cost $10 a week.

How would he pay for it? There were no spare jobs to be had in Chicago at that time, since the city was flush with farm boys from the South, who came to the city during the winter to find work. Uncle Charles must have sent a letter to Littlewood asking him to recommend a part-time job, while he took courses.

The second part of this article series will continue with Uncle Charles’ quest for higher education, his short stay in Chicago, and what happened afterwards. I must agree with Mr. W. H. Littlewood—Uncle Charles was persistent.

This is fascinating . We did not see Uncle Charles and Aunt Leona very often but I have many memories.

It was a big trip (when I was a child ) to go visit them and I remember Uncle Charles taking us to where he worked . I am looking forward to part 2 . Thank you Mark and Leon !

Very interesting. I have no recollections of Uncle Charles. I drove Mom, Aunt Ellen, and my daughter Melani, to Massachusetts for his funeral.