Making Bank: Clues About Hagenbuchs and Their Money

There was a time in American history when a dollar wasn’t always a dollar and when your local bank was more likely to have printed the paper money in your wallet than the federal government. Joshua R. Greenberg describes this system in his book Bank Notes and Shinplasters: The Rage for Paper Money in the Early Republic, which I recently finished reading. This got me thinking about how our early Hagenbuch ancestors would have used and thought about money.

Prior to the Civil War in the 1860s, the United States was more decentralized, gave greater freedom to individual states, and had fewer banking regulations. This led to a monetary system that was far different from the one we have presently.

Gold and silver coins, known as specie, were the most trusted and universally accepted form of currency, due to the underlying value of these metals. A $1 coin typically held its value regardless of where it was spent in the young republic. But specie had several drawbacks as currency. Precious metals were difficult to carry and often in short supply. Timothy Hagenbuch (b. 1804) confirms this in his 1839 letter to his brother, Enoch, when he writes that silver coins were more plentiful then than at any time in the previous 10 years. Just imagine our ancestors lacking enough coins to make change or pay for the items they wanted to buy!

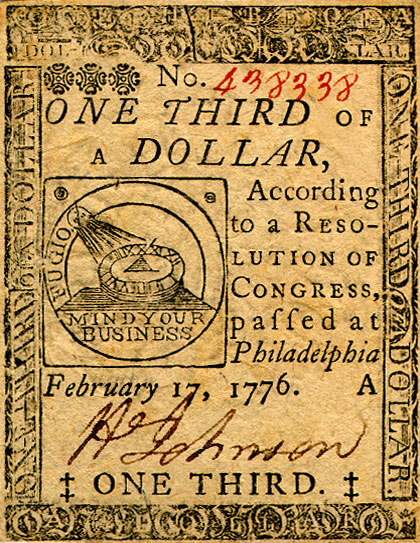

Scarce coinage led many places to begin printing more paper money, which functioned as promissory notes. These were easier to create, distribute, and carry, although they were a fiat currency with no intrinsic value. However, a paper note could be presented to the entity that printed it (e.g. a bank, business, or government) and the holder would receive specie in return. The ability to redeem paper for gold and silver helped to win the public’s trust in it as currency.

Paper money that was poorly capitalized (i.e. without enough specie to redeem it) quickly became worthless. Such was the case when the Continental Congress printed too much money during the Revolutionary War period. When Andreas Hagenbuch (b. 1715) died in 1785, an inventory of his estate showed that he held $3500 in devalued Continental money.

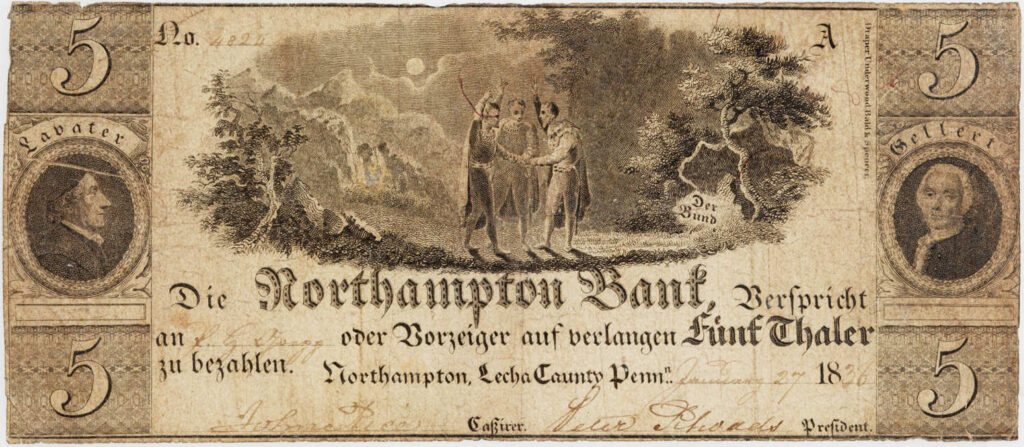

Yet, before 1860 most of the paper money in circulation had not been printed by the federal government. Rather, it was printed by local, state-charted banks throughout the country. The banknotes were hardly uniform in appearance and had a wide array of unique designs. For example, the Northampton Bank in Allentown, Pennsylvania printed notes that were in Deitsch rather than English. This appealed to their customers, many of whom were of German ancestry.

Distinguishing good money from bad was a challenge. To better understand this, we can imagine a transaction between Timothy Hagenbuch’s father, Jacob (b. 1777), and a customer, who has stopped by the family homestead in Berks County, PA. The customer offers to buy some corn for $1. Jacob agrees, hoping to receive a note from a nearby bank in Reading, PA. Instead, the customer hands him a $1 bill from a faraway bank in Dayton, Ohio.

What does Jacob do? If he accepts the note, then he must travel to Dayton to redeem it for specie. If he rejects it, perhaps worrying the bank may have closed or might lack enough specie to redeem the note, he risks losing the sale.

Ultimately, Jacob decides to do neither. He chooses to negotiate with the customer, offering to accept the $1 bill from Dayton at a discount of 25%. The customer agrees and Jacob hands the man 75¢ of corn for the $1 note. Neither man would have seen this as unusual, since out-of-state banknotes were commonly discounted during transactions. In fact, information about the health of different banks and the suggested rates for discounting their bills was often published, assisting everyday Americans in making monetary decisions.

Jacob now holds a $1 banknote from Dayton, which puts him in a similar position to the customer. He can either take the note to Ohio for redemption or pass the bill to someone else, who may accept it at a discount. Given the cost of a trip to Dayton, Jacob decides upon the latter and sells the $1 bill to a carpetbagger for 80¢ and makes a 5¢ profit. He sells some other out-of-state notes too.

Carpetbaggers (a name that took on a different meaning after the Civil War) would purchase bills issued by faraway banks and travel to redeem these en masse. The carpetbaggers had knowledge of the banking system and used this to profit from the inefficient, decentralized financial system. Because the carpetbagger paid 80¢ for the $1 bill, he expects to make a 20¢ profit upon redeeming it for specie in Dayton.

Also, during the transaction with Jacob, the carpetbagger offers him a $20 banknote from the Commercial Bank of Florida—at a discount of course. Jacob accepts the offer, speculating that he might be able to pass it to someone else at a lesser discount and netting a profit. The 1842 inventory of Jacob’s estate mentions such a $20 banknote from Florida.

Banks had a financial incentive to circulate their bills as far away as possible. Since they could print their own money, the banks would distribute their notes through loans and payments to customers. Sometimes there were strings attached, like a requirement to spend the money in distant towns. This made it more difficult for people to redeem the notes and protected a bank’s supply of specie.

The Civil War brought immediate social and political changes to the United States. Additionally, it spelled the end of the loose banking regulations that led to the proliferation of individual banks printing their own notes.

Today we take for granted our federally regulated money supply, something our early Hagenbuch ancestors hardly knew. With the invention of decentralized cryptocurrencies, like Bitcoin, some experts have suggested that the future of money might look more like the past—less government control and constantly fluctuating values. Only time will tell!