1789 Essay on the Pennsylvania Deitsch, Part 1

The Hagenbuch family arrived in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania in 1737 and were part of one of the earliest waves of German immigrants to the colony. By the late 18th century, Pennsylvania’s German or “Deitsch” residents comprised a sizable portion of the state’s population.

Deitsch families, such as the Hagenbuchs, had a unique language, traditions, and culture. While they didn’t avoid the modern world like today’s Amish do, they were seen as a distinct subset of the Pennsylvania populace, especially when compared to other English-speaking residents from the British Isles.

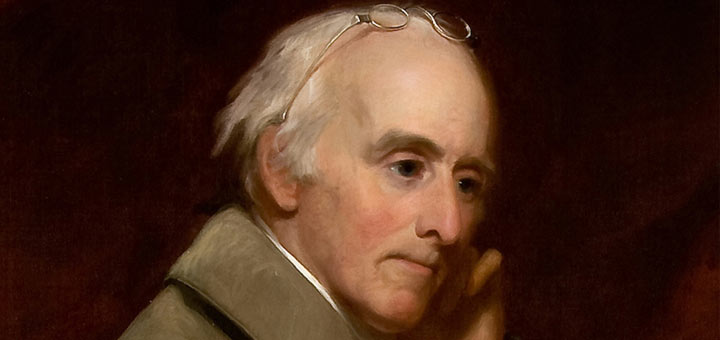

When researching historical topics, it can be difficult to find relevant, contemporary sources. Thankfully, Benjamin Rush (b. 1745, d. 1813) wrote an account of Pennsylvania’s Deitsch citizens in 1789 titled An Account of the Manners of the German Inhabitants of Pennsylvania. Rush was an educator, physician, and politician. He signed the Declaration of Independence and founded Dickinson College in Carlisle, PA.

Since it was first published, Rush’s essay has been edited, annotated, and reprinted several times. Most recently, it was used as a source for and included within Cynthia G. Falk’s book, Architecture and Artifacts of the Pennsylvania Germans. Falk’s book also uses the plans for Christian Hagenbuch’s (b. 1747) house as a source too.

Benjamin Rush’s account provides a fascinating look at Pennsylvania’s Deitsch people, as written from the perspective of an English-speaking outsider. Given the length of the piece, it has been slightly edited and will be published in a series of three parts.

An Account of the Manners of the German Inhabitants of Pennsylvania

The state of Pennsylvania is much indebted for her prosperity and reputation, to the German part of her citizens, that a short account of their manners may, perhaps, be useful and agreeable to their fellow citizens in every part of the United States.

The older Germans, and the ancestors of those who are young, migrated chiefly from the Palatinate: from Alsace, Swabia, Saxony, and Switzerland. But natives of every principality and dukedom in Germany are to be found in different parts of the state. They brought little property with them. A few pieces of gold or silver coin, a chest filled with clothes, a Bible, and a prayer or a hymn book, constituted the whole stock of most of them. Many of them bound themselves, or one or more of their children, to masters after their arrival for four, five, or seven years, in order to pay for their passages across the ocean. A clergyman always accompanied them when they came in large bodies.

The principal part of them were farmers; but there were many mechanics, who brought with them a knowledge of those arts which are necessary and useful in all countries. These mechanics were chiefly weavers, tailors, tanners, shoemakers, comb makers, smiths of all kinds, butchers, bakers, paper makers, watchmakers, and sugar bakers. I shall begin this account of the German inhabitants of Pennsylvania by describing the manners of the German farmers.

This body of citizens are not only industrious and frugal, but skillful cultivators of the earth. I shall enumerate a few particulars in which they differ from most of the other farmers of Pennsylvania.

1st. In settling a tract of land, they always provide large and suitable accommodations for their horses and cattle before they lay out much money in building a house for themselves. The barn and the stables are generally under one roof and contrived in such a manner as to enable them to feed their horses and cattle and to remove their dung, with as little trouble as possible. The first dwelling house upon this farm is small and built of logs. It generally lasts the life time of the first settler of a tract of land. Hence they have a saying that “a son should always begin his improvements where his father left off.” This is by building a large and convenient stone house.

2nd. They always prefer good land or that land on which there is a large quantity of meadow ground. From an attention to the cultivation of grass, they often double the value of an old farm in a few years, and grow rich on farms on which their predecessors of whom they purchased them, have nearly starved. They prefer purchasing farms with some improvements to settling on a new tract of land.

3rd. In clearing new land, they do not girdle the trees simply, and leave them to perish in the ground, as is the custom of their English or Irish neighbors; but they generally cut them down and burn them. In destroying under-wood and bushes, they generally grub them out of the ground. By this means a field is as fit for cultivation the second year after it is cleared as it is in twenty years afterwards. The advantages of this mode of clearing, consist in the immediate product of the field and in the greater facility with which it is plowed, harrowed, and reaped. The expense of repairing a plow, which is often broken two or three times in a year by small stumps concealed in the ground, is often greater than the extraordinary expense of grubbing the same field completely in clearing it.

4th. They feed their horses and cows, of which they keep only a small number, in such a manner that the former perform twice the labor of those horses, and the latter yield twice the quantity of milk of those cows, that are less plentifully fed. There is great economy in this practice, especially in a country where so much of the labor of a farmer is necessary to support his domestic animals. A German horse is known in every part of the state. Indeed he seems to “feel with his lord, the pleasure and the pride” of his extraordinary size or fat.

5th. The fences of a German farm are generally high and well built, so that his fields seldom suffer from the inroads of his own, or his neighbors, horses, cattle, hogs, or sheep.

6th. The German farmers are great economists of their wood. Hence they burn it only in stoves, in which they consume but a fourth or fifth part of what is commonly burnt in ordinary open fire places. Besides, their horses are saved, by means of this economy, from that immense labor of hauling wood in the middle of winter, which frequently unfits the horses of their neighbors for the toils of the ensuing spring. Their houses are, moreover, rendered so comfortable, at all times, by large closed stoves, that twice the business is done by every branch of the family, in knitting, spinning, and mending farming utensils, that is done in houses where every member of the family crowds near to a common fireplace or shivers at a distance from it, with hands and fingers that move by reason of the cold with only half their usual quickness.

They discover economy in the preservation and increase of their wood in several other ways. They sometimes defend it, using high fences, from their cattle, though such means the young forest trees are able to grow and replace those that are cut down for the necessary use on the farm. But where this cannot be conveniently done, they surround the stump of that tree which is most useful for fences, like the chestnut, with a small triangular fence. From this stump a number of suckers shoot out in a few years, two or three of which, in the course of five and twenty years, grow into trees of the same size as the tree from whose roots they derived their origin.

7th. They keep their horses and cattle as warm as possible in winter, by which means they save a great deal of their hay and grain. For these animals, when cold, eat much more than when they are in a more comfortable situation.

8th. The German farmers live frugally in their families, with respect to diet, furniture and apparel. They sell their most profitable grain, which is wheat, and eat that which is less profitable but more nourishing, like rye or Indian corn. The profit to a farmer from this single article of economy is equal, in the course of a lifetime, to the price of a farm for one of his children. They eat sparingly of boiled animal food, and prefer large quantities of vegetables, particularly salad, turnips, onions, and cabbage, the last of which they make into sauerkraut. They likewise use a large quantity of milk and cheese in their diet. Perhaps the Germans do not proportion the quantity of their animal food, to the degrees of their labor. Hence it has been thought by some people, that they decline in strength sooner than their English or Irish neighbors. Very few of them ever use distilled spirits in their families. Their common drinks are cider, beer, wine, and simple water. The furniture of their house is plain and useful. They cover themselves in winter with light feather beds instead of blankets. In this contrivance there is both convenience and economy, for the beds are warmer than blankets and they are made by themselves. The apparel of the German farmers is usually homespun. When they use European articles of dress, they prefer those which are of the best quality and of the highest price. They are afraid of debt and seldom purchase any thing without paying cash for it.

9th. The German farmers have large or profitable gardens near their houses. These contain little else but useful vegetables. Pennsylvania is indebted to the Germans for the principal part of her knowledge in horticulture. There was a time when turnips and cabbage were the principal vegetables that were used in the diet of the citizens of Philadelphia. This will not surprise those persons who know that the first English settlers in Pennsylvania left England while horticulture was in its infancy in that country. It was not until the reign of William III that this useful and agreeable art was cultivated by the English nation. Since the settlement of a number of German gardeners in the neighborhood of Philadelphia, the tables of all classes of citizens have been covered with a variety of vegetables in every season of the year; and the use of these vegetables in diet may be ascribed to the general exemption of the citizens of Philadelphia from diseases of the skin.

10th. The Germans seldom hire men to work upon their farms. The feebleness of that authority which masters possess over hired servants is such that their wages are seldom procured from their labor, except in harvest, when they work in the presence of their masters. The wives and daughters of the German farmers frequently forsake for a while their dairy and spinning-wheel, and join their husbands and brothers in the labor of cutting down, collecting, and bringing home the fruits of the fields and orchards. The work of the gardens is generally done by the women of the family.

11th. A large and strong wagon, covered with linen cloth, is an essential part of the furniture of a German farm. In this wagon, drawn by four or five large horses of a peculiar breed, they convey to market over the roughest roads between two to three thousand pounds weight of the produce of their farms. In the months of September and October, it is no uncommon thing on the Lancaster and Reading roads to meet in one day from fifty to a hundred of these wagons on their way to Philadelphia, most of which belong to German farmers.

12th. The favorable influence of agriculture, as conducted by the Germans in extending human happiness, is manifested by the joy they express upon the birth of a child. No dread of poverty, nor distrust of providence from an increasing family, depress the spirits of these industrious and frugal people. Upon the birth of a son, they exult in the gift of a plowman or a wagoner; and upon the birth of a daughter, they rejoice in the addition of another spinster or milk-maid to their family. Happy state of human society! What blessings can civilization confer, that can atone for the extinction of the ancient and patriarchal pleasure of raising up a numerous and healthy family of children to labor for their parents, for themselves, and for their country; and finally to partake of the knowledge and happiness which are annexed to existence! The joy of parents upon the birth of a child is the grateful echo of creating goodness. May the mountains of Pennsylvania be forever vocal with songs of joy upon these occasions! They will be the infallible signs of innocence, industry, wealth and happiness in the state.

13th. The Germans take great pains to produce in their children, not only habits of labor, but also a love of it. In this they submit to the irreversible sentence inflicted upon man in such a manner as to convert the wrath of heaven into a private and public happiness. “To fear God and to love work,” are the first lessons they teach their children. They prefer industrious habits to money itself; hence, when a young man asks the consent of his father to marry the girl of his choice, he does not inquire so much whether she be rich or poor, or whether she possess any personal or mental accomplishments. Rather he asks whether she be industrious and acquainted with the duties of a good housewife.

The remainder of this essay will be posted in parts two and three.